Viewpoint: US media lax on drones

- Published

- comments

A predator drone in 2010

The media has been slow to fully report on the US drone programme, says Tara McKelvey, a correspondent for Newsweek Global and The Daily Beast. Is the truth finally starting to come out?

During a briefing on 5 February, external, White House press secretary Jay Carney spoke in a business-like manner about a leaked document regarding the government's targeted-killing programme.

"You should read it," he told reporters. "It's a click away." He did not seem bothered by the document, a white paper that had been obtained by NBC News' Michael Isikoff, external.

Nor should he be. Unlike many leaked documents, the white paper did not expose shocking information. Instead, it showed the government's legal argument for drone strikes against Americans, a campaign that has been under way for several years.

Mr Carney's advice to reporters - that they should look closely at the leaked document - shows the bipolar nature of the drone programme: rarely acknowledged by officials, yet widely known.

"Our policy process is tied up in knots because we can't even acknowledge basic facts," says Steven Aftergood, who looks at secrecy issues for the Federation of American Scientists.

"Fortunately, there are reporters who are willing to poke around."

Sometimes, reporters reveal details about the programme, as Michael Isikoff of NBC News did.

Too often, however, American journalists have relied on government sources to explain the story and presented an overly optimistic view of the programme. Or journalists have not reported stories that they could have.

For instance, the Washington Post held a story about a drone base in Saudi Arabia for some time - because, they explained, administration officials had asked them to.

A CIA spokesman said he could not talk about the matter, adding: "We're being extra cautious about this."

Once the Post editors heard the New York Times was planning to run a story about the base, they published their piece, external.

The unveiling of the government's legal arguments and the Saudi base come shortly before a Senate confirmation hearing for John Brennan as CIA director.

He has been one of the architects of the programme in Pakistan, a campaign that has been ramped up since 2009.

President Barack Obama has signed off on hundreds of strikes, nearly seven times the number President George W Bush authorised during his two terms, according to the Washington-based New America Foundation, external.

Yet despite the controversial nature of using drones, which raises legal and moral questions, American journalists have been relatively restrained in their coverage and they have tended to report on the drone programme from the perspective of the United States government.

That is natural, says Arthur Brisbane, the former public editor for the New York Times. "The Times doesn't function in a way that's detached from the national interest," he says.

Philip Alston, the former United Nations special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, someone who has been critical of the use of drones, says: "It's a little like Olympics games coverage.

"When you watch Australian TV, you'd think only the Australians are competing."

Americans have been rooting for the drones. According to a Washington Post-ABC News Poll in February 2012, 83% of people in this country support the drone programme.

"A UAV doesn't have a mom," a retired military officer told me, using an acronym for an unmanned aerial vehicle, or drone. "If a UAV is destroyed, no-one cares."

The drone strikes are part of a tradition for American forces, which rely heavily on air power. Previous bombing campaigns such as B-52 strikes in Vietnam and aerial campaigns in Bosnia and Serbia also provoked concerns.

In all of these conflicts, however, Americans favoured surgical air strikes over the deployment of ground troops.

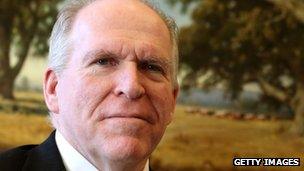

CIA director nominee John Brennan helped develop the current drone programme

US media coverage reflected the nation's support for the use of drones during the early years of the Obama administration, as I discovered during my research on the subject.

By their own account, many journalists began to examine the drone programme only in the later years of Mr Obama's first term.

It was a shift caused less by the passage of time than by several events: the killing of an American, Anwar al-Awlaki, in Yemen in 2011, and an April 2012 speech given by nominated CIA director John Brennan, in which he spoke about "moral questions" regarding the strikes, a presentation that coincided with an expansion of the programme.

The month after his speech, the New York Times, the Washington Post, Time, the Christian Science Monitor and the Wall Street Journal published 88 articles, nearly twice as many as the previous month, one of the biggest spikes in coverage since 2009.

These events caused a change in both the volume of coverage, which increased dramatically, and also in the stories.

Afterwards, American journalists began to write more analytical and investigative articles about the programme, despite a reporting environment that has been marked by secrecy and paranoia.

As the programme continues to expand, secrecy experts like Steven Aftergood believe it will become even more important for Americans to know about it so they can debate its merits.

Jay Carney was willing to discuss the programme this week, mainly because NBC News published the paper.

Bit by bit, the story is coming out.

McKelvy was a 2012 fellow at Harvard's Shorenstein Center.

- Published6 February 2013

- Published5 February 2013