The cost of Obama's secret drone war

- Published

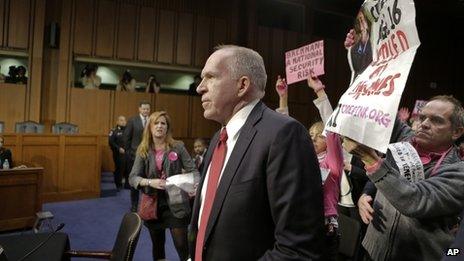

Protesters at the Senate confirmation hearing for CIA nominee John Brennan

By the time John Brennan, President Barack Obama's nominee to be the next director of the Central Intelligence Agency, finished three hours of public testimony before the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, two things were clear.

First, Mr Brennan will be confirmed. And second, despite nearly a dozen years of war, there are profound disagreements both within the United States and beyond about how this conflict has been and should be waged.

Mr Brennan provided a forceful defence of the Obama administration's war against al-Qaeda over the past four years, particularly its increased employment of drones in various countries he declined to specify.

He made clear that the administration believes it has the legal authority to use lethal force in self-defence against al-Qaeda and associated forces wherever there is an imminent threat against the United States and capture is not feasible.

The committee was clearly supportive of the continued use of drones in the ongoing war against al-Qaeda. Americans by a wide margin share this view.

But that is not the case outside the United States. The rest of the world questions the legality of their use, viscerally so in a country such as Pakistan, where drone attacks increased significantly during President Obama's first term.

While Mr Brennan declined to discuss where drones are employed, Ambassador Sherry Rehman, Pakistan's ambassador to the United States, displayed no such reticence.

In a discussion with reporters in Washington two days before Mr Brennan's testimony, she made clear that the civilian government in Islamabad views America's continued deployment of drones as a violation of Pakistan's sovereignty, as well as strategically counter-productive.

"We need to drain this swamp and instead it [the drone campaign] is radicalising people," Ambassador Rehman said.

Some 74% of Pakistanis polled by Pew last year termed the US an "enemy"

"It creates more potential terrorists on the ground and militants on the ground instead of taking them out. If it's taking out, say, a high-value or a medium-value target, it's also creating probably an entire community of future recruits."

Recent polling tends to support Ambassador Rehman's view.

An estimated 74% of Pakistanis polled by Pew last year termed the United States an "enemy." Drones are a clear factor.

Mr Brennan says the administration takes into account the potential backlash from ongoing counter-terrorism operations.

But rather than address Pakistani concerns publicly as part of a long-term public diplomacy approach, the Obama administration has chosen, at least at the moment, to pretend the problem does not exist.

It refuses to acknowledge (despite widespread news reports) the existence of a drone campaign in Pakistan.

Whether this approach is sustainable and for how long is an open question.

According to Pakistani authorities, whether or not there was close co-ordination regarding drone operations in the past, there is none now.

Ambassador Rehman denies that Pakistan criticises the use of drones in public, but co-operates in private.

"There is no question of any quiet complicity. No question of wink and nod," she insisted.

This represents a genuine conundrum for the Obama administration. There is no question that drone strikes have been a major factor in virtually eliminating the strategic threat posed by core al-Qaeda.

But what started out as a strategic campaign against high-value targets has morphed into something far more tactical.

Drones are increasingly employed not against al-Qaeda operatives plotting attacks against the American homeland, but to target lower-level Taliban forces that continue to attack US forces in Afghanistan.

Presumably, Washington wants to keep up pressure on al-Qaeda's sanctuary in the tribal areas until US forces withdraw from Afghanistan in 2014.

The wreckage of a car destroyed by a US drone strike in south-eastern Yemen in February 2013

But at what cost?

At the start of the Obama administration, strengthening of civilian governmental institutions in Pakistan was considered the long-term solution to extremism linked to Pakistan.

Now the drone campaign undercuts the very civilian government the United States is spending billions in aid to build up.

Relations between the two countries have stabilised, but the lack of trust remains deep.

The Pakistani parliament has made clear that drones are a "red line", one Washington chooses for the moment to ignore, putting its long-term standing and influence with Pakistan in jeopardy.

"Every time there is a drone strike, you see it on 40 channels at least in Pakistan," said Ambassador Rehman.

"They lend an unfortunate view of US power and how the United States projects its power abroad."

Drones may be a key element in the US strategy, but as Ambassador Rehman makes clear, they are "not part of our playbook. The time for drone strikes is really over."

But based on the Brennan hearing, there is no indication the United States plans to follow her advice any time soon.