A press conference divided by a common purpose

- Published

- comments

Ask them anything, except what to do on Syria

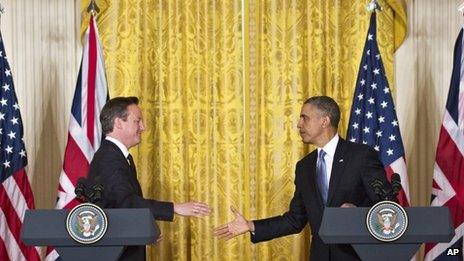

The news conference held by President Obama and the UK Prime Minister, David Cameron, was a clear example of two nations divided by a common purpose.

The purpose was the desire of the British and American media to get under the skin of their leaders, and ask awkward questions. But they were interested in completely different stories.

Given that each country's journalists were only granted one question apiece it was a tribute to their deployment of the multi-warhead portmanteau question that they actually got answers on everything that mattered.

IRS, Benghazi and the EU

For the American press it was Mr Obama's take on the Internal Revenue Service's (IRS) apparent persecution of the Tea Party movement that was most interesting.

He obliged while hedging his bets a bit. He said if it had happened, it was "outrageous", against all the traditions of impartiality.

On Benghazi he was a good deal more feisty, even fed up. He suggested the continuing accusations of a cover-up were politically motivated, defied logic, and dishonoured those who serve the US abroad.

The whole tale has become so highly hyper-partisan, with some denying there was any hanky panky at all around the briefing notes, and others concocting a tottering, towering conspiracy, that it is hard to find anyone in the US media seeking the rational kernel of truth - but this New York Times article does a good job, external.

David Cameron was pursued by the Conservative Party's familiar family ghost - questions of the UK's relationship with the EU.

President Obama came to his aid, suggesting that Britain's place as an "active, robust and engaged" country meant it should be in the European Union.

He then stuck his neck out further, arguing Mr Cameron was right to attempt to fix an apparently broken relationship before breaking the whole thing off. The president is a better friend to the prime minister than some party colleagues.

The US genuinely would be alarmed if Britain really did exit the EU stage right, but at this point this was more about helping a pal than ringing alarm bells.

Anything but Syria

Then there was Syria, which will not make many headlines, but probably was a main focus of the talks themselves.

Mr Cameron came across as more eager, stressing the urgency of the situation and the worth of the Russian peace talks.

The difference in tone is probably because Mr Cameron is more of an enthusiastic liberal interventionist than his ally, who is adverse to overt US engagement in the Middle East and sees Syria as difficult and dangerous to fix.

They both said they and the Russians wanted the same thing - a stable Syria without extremism. They did not add that the Russians think that was the situation two years ago.

Conventional wisdom is that all senior politicians end up turning their attention to foreign affairs because at least they can do something, whereas the domestic agenda is insoluble.

It is a testimony to the intractability of the Syrian conflict that even innuendo over the IRS and the Tory civil war seem attractive by comparison.

- Published13 May 2013

- Published10 May 2013