Viewpoints: New approach to prison and the war on drugs

- Published

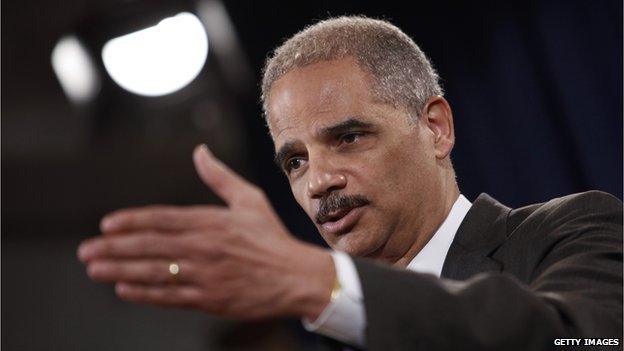

Holder said on Monday the US cannot "incarcerate our way to a safer nation"

US Attorney General Eric Holder has announced that mandatory minimum sentences will no longer be imposed in certain kinds of federal drug cases. Experts take a close look at the change in policy.

People convicted of drug-related crimes have received heavy sentences in this country for years, under the decades-old War on Drugs policy backed by US presidents of both parties. But now, Mr Holder wants to change things.

Under a policy shift unveiled on Monday, people convicted under federal law of non-violent drug-related offenses who have no ties to gangs or cartels will not necessarily face decades behind bars.

Under the reforms, Mr Holder is directing federal prosecutors who draft indictments for certain drug offences to omit any mention of the quantity of illegal substance involved, so as to avoid triggering a mandatory minimum sentence.

Analysts discuss his announcement and its implications for crime and the nation.

Eugene Jarecki, film director, The House I Live In

Mr Holder has announced that our criminalisation of drug addicts has been a failure. The American War on Drugs has now officially begun to end.

What will replace it? For my documentary film, The House I Live In, external, I interviewed hundreds of participants in our criminal justice system, including judges, prosecutors, defence lawyers, rehabilitators, narcotics officers and addicts, all of whom were involved in a collaborative search for a way to reform the system.

By and large, they all agree the system has failed, but they differ in their proposed solutions. Today, Mr Holder suggested his answer, and more than once indicated that he has President Barack Obama's support.

Mr Holder called for an important step, being "smart on crime", a phrase memorialised in the film by Charles Ogletree, a Harvard professor recognised as Mr Obama's mentor. This notion replaces the idea of being merely "tough on crime", as we cannot "incarcerate our way to a safer nation". These are Mr Holder's words.

He said we must be efficient and consider the individual, and we must redirect resources from prison-building to programmes, as the status quo is unsustainable.

"This is about who we are," Mr Holder declared, echoing the views of so many in my film. He made it clear that it's our obligation to align our criminal justice system with our most sacred values.

A better time is at hand. And so many of us are ready for changes that will positively affect the lives of so many.

Beau Kilmer, co-director, RAND Drug Policy Research Center; co-author, Marijuana Legalization: What Everyone Needs to Know

Today the Obama administration announced its intention to reduce the number of federal prisoners in the US. The proposed actions are long overdue, and they make sense both socially and fiscally.

Most noteworthy is the reported plan to reduce the use of federal mandatory minimum drug sentences.

This approach will give judges more discretion when handling these cases, allowing them to tailor sentences and services to these offenders.

This can help reduce some of the racial disparities associated with these laws and help reintegrate these individuals back into their families and communities.

The administration also renewed its commitment to providing drug treatment to those in the criminal justice system who struggle with substance use problems. This makes sense for taxpayers.

Research from RAND, external has shown that if you want to reduce cocaine consumption and drug-related crime, you get more bang for the buck if you put money into treatment rather than paying for the increase in incarceration produced by federal mandatory minimum sentences.

But not all heavy users in the criminal justice system need formal treatment to reduce their consumption. Emerging research on programs in Hawaii and South Dakota finds that frequent testing combined with swift, certain and modest sanctions reduces consumption for some heavy users and improves public safety outcomes.

Eli Lehrer, president, conservative think tank R Street Institute

Mr Holder's speech offered more symbolism than substance.

Many of the reforms Mr Holder announced actually have limited impact. The changes in policies relating to mandatory minimum drug sentences that Mr Holder has ordered, for example, apply only to "low-level, non-violent drug offenders who have no ties to large-scale organizations, gangs, or cartels".

This will have an impact on only a handful of cases because lower-level offenders typically get caught in the federal system when they are tied to such gangs.

Diversion programmes, which send non-violent drug offenders to treatment rather than prison, are likewise worthy of the praise Mr Holder has lavished on them. However, they already exist in every sizeable American jurisdiction and have received similar praise over the past quarter century.

Even prisoner re-entry, another topic Mr Holder touched on, is hardly new. Officials under President George W Bush paid attention to this subject at the highest levels, and the Obama administration has mostly continued its programmes.

Nevertheless, the speech was still important because it shows how much the public conversation about crime has changed. Between the late 1950s and early 1990s, crime and fear of crime dominated American politics.

Since the 1990s, however, crime has declined (gross rates are now lower than those in the UK), and the issue has slipped so far down in priority that neither President Obama nor presidential candidate Mitt Romney so much as mentioned it during their debates.

This shift allows officials like Mr Holder to take a more nuanced approach towards crime and give public speeches that emphasise a view other than "lock 'em up".

And that, if nothing else, shows that America's public policies relating to crime are getting smarter.

- Published12 August 2013