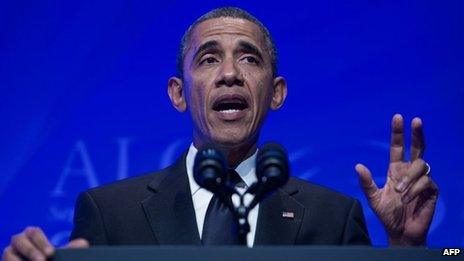

Will Obama solve a foreign policy paradox?

- Published

- comments

Will this year's United Nations meeting vindicate or complicate Barack Obama's foreign policymaking?

It is not exactly veni vidi vici: "I came, I saw, I conquered."

Maybe instead: vacillate, vindicate, victory? President Barack Obama's foreign policy has looked sometimes incoherent, sometimes less than robust and that has come to a head in the last month.

But he could be on the path to vindication in New York this week. A combination of sanctions and the hand of friendship may have resulted in a conciliatory tone from Iran's new President, Hassan Rouhani.

Syria could be on the path to chemical weapons disarmament without an American shot being fired. Of course, there is lots that could still go wrong there.

While the peacemakers may be blessed, Mr Obama has endured a lot of cursing along the way. Commentators are almost universal in mocking his abrupt policy swerves over the last few weeks.

Three viewpoints

It seems to me that three voices war in the US president's head. And his almost public agonising is his attempt to reconcile them.

First, there is his imperative to reduce America's visible footprint in the world and avoid foreign wars.

It is one reason he was elected, to end the wars and concentrate on the homefront. He doesn't want his country to look like the world's bully.

Iran president in nuclear weapons pledge

Then there is his duty to protect national security. But uncomfortably alongside both of these there is a desire to protect the unprotected and be on the side of liberation and justice.

And there are other voices from outside, calling for the United States to lead the world, and act when others won't.

As Mr Obama has observed, many people don't like it when America does impose its will on the world, and are equally dismayed when it doesn't.

His resolution of this paradox seems to be to threaten the use of military action, but go to some lengths to avoid using it, or taking a back seat as in Libya.

But this is not without consequences. Mr Obama will doubtless emphasis his oft-stated view this week that only the firm threat of threat of military force has brought Syria to the negotiating table.

Difficult precedent

It is less clear if military action is really still an option.

My guess is that it won't be authorised in any UN resolution. There will be something vague about it still being a possibility.

But consider this: public opinion in the US and UK was against taking action against Syria. The British Parliament voted against it. Congress was all set to do the same.

What was proposed was a limited strike against a bloody regime accused of massacring its own people and committing a war crime.

Then ask how much enthusiasm would there be to attack a country for apparently trying to build a nuclear weapon, although it says it isn't.

If Syria used chemical weapons again or stormed out of talks that might be one thing. But what if it drags its feet, and says it will take three months to hand over weapons, rather than two weeks, and gives inspectors the run around? Could that be a casus belli?

It is true neither David Cameron nor Mr Obama have to win a vote - but they have set a precedent that would be difficult to ignore.

So they will give peace a chance.

A senior official mused dryly that Obama's policymaking was a "complicated way of making a sausage".

"But it might be quite a good sausage in the end."