Mardell: Presidential puzzle

- Published

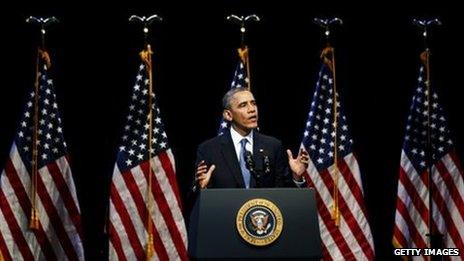

US President Barack Obama addressed the nation's income inequality in a recent speech

The demands of striking fast-food workers, external have the backing of President Barack Obama, who proposed a raise in the minimum wage back in his state of the union, external address 12 months ago.

It still hasn't happened.

He recently said in a big speech, external that he'd keep pushing for a higher minimum wage, external which would be "good for our economy [and] good for our families".

That doesn't mean it is going to happen.

Elusive American dream

The speech itself was a sweeping panorama on the increasingly elusive American dream - what he called "the dangerous and growing inequality" and lack of upward mobility.

His theme was so important, he said, it was the very reason he wanted to become president, it was "the defining challenge of our time, external".

It doesn't mean anything is going to happen.

This raises what, to me, is the puzzle at the heart of Mr Obama's presidency. What does he think he is here for?

Often he looks like the inspirational in pursuit of the unattainable.

The minimum wage is part of a long list, from gun control to immigration reform, of things that he would like to do but can't because of Republicans in Congress.

So he makes speeches about them.

Words do matter

Now words do matter. They are a politician's ammunition.

In theory at least, if he was persuasive enough, he could help sweep away the opposition to his policies by winning back the House in next year's midterm elections. But few think that is really going to happen.

In this scathing article, external, Peggy Noonan, former President Ronald Reagan's speechwriter, argues that Mr Obama has been exposed as a man of words and not action, and that is the result of a style of government.

Former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher also lamented the constraints of government (file photo)

It's harsh but worth considering, not least because Mr Obama should have been aware of the pitfalls of the job.

The feeling of powerlessness of the very powerful is well known.

A British minister once told me that Mrs Thatcher used to sit in her flat above Number 10 watching some piece of news, complaining that the government really should stop it happening (whatever it was). Her husband would gently point out that she was Prime Minister.

Mr Obama must feel the same.

He is the most powerful man in the world, according to one cliche, but he can't get anything he wants done.

Mr Obama is very good at analysing a problem, expressing it and crusading, exhorting, campaigning on it.

But it is increasingly obvious that he hasn't found a way of getting stuff done.

- Published3 December 2013

- Published3 December 2013

- Published1 December 2013

- Published25 November 2013

- Published25 November 2013

- Published25 November 2013

- Published20 January 2014

- Published24 November 2013