Abu Hamza in the dock - and why he shed tears

- Published

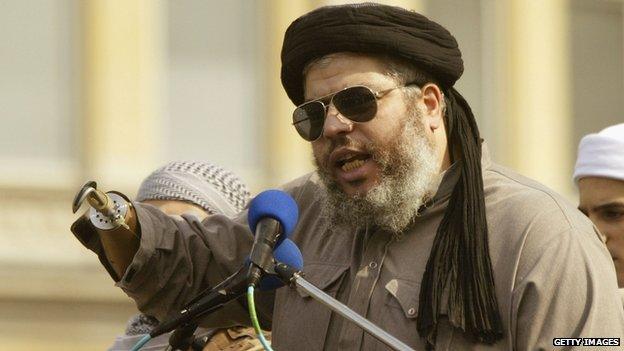

Abu Hamza, shown here in London in 2002, gave fiery sermons at Finsbury Park mosque

With his courtroom testimony, Abu Hamza tries to dispel the notion that he is a pantomime villain. He makes jurors laugh - and cries over people who were killed in Srebrenica.

Abu Hamza has been charged with being involved in a kidnapping conspiracy - the assault occurred in Yemen in 1998 - as well as with providing material support to al-Qaeda and helping to establish a training camp for militants in Bly, Oregon.

He has pleaded not guilty. And his lawyer, Joshua Dratel, has his work cut out for him.

The goal of a lawyer in a terror trial is to make his client personable, or at least less demonic. The job is made harder by the nature of the offences - and also by the way terror suspects are vilified by journalists and politicians.

Writers for the New York Post, external describe Abu Hamza, whose real name is Mustafa Kamel Musafa, as a "one-eyed, hook-handed hate preacher", referring to his physical deformities.

"He was quite fierce - a big guy with a long beard," says Richard Barrett, formerly of MI6 and now with the New York-based Soufan Group. "He captured the public imagination."

It does not help that Abu Hamza, 56, once described Osama Bin Laden as "a reformer, a victim of American polices and a good-hearted person", according to court papers in New York.

Before the trial started, Abu Hamza wrote to the judge, Katherine Forrest, and said that he thought his remarks in the courtroom would be "important for historians, researchers, investigative journalists and analysts".

When counterterrorism experts hear that, they laugh.

"That's nonsense," says Mitchell Silber, former director of the analytic unit of New York Police Department's Intelligence Division and the author of The Al Qaeda Factor. "I'm sure he's testifying for his own self-interest."

Ken Ballen, a former federal prosecutor who interviewed hundreds of Islamic radicals for his book, Terrorists in Love, says: "He's doing this for propaganda purposes."

Abu Hamza's decision is unusual.

Defendants rarely testify in the US. Lawyers advise against it because the defendants may come across poorly during cross-examination.

Sometimes, though, they speak.

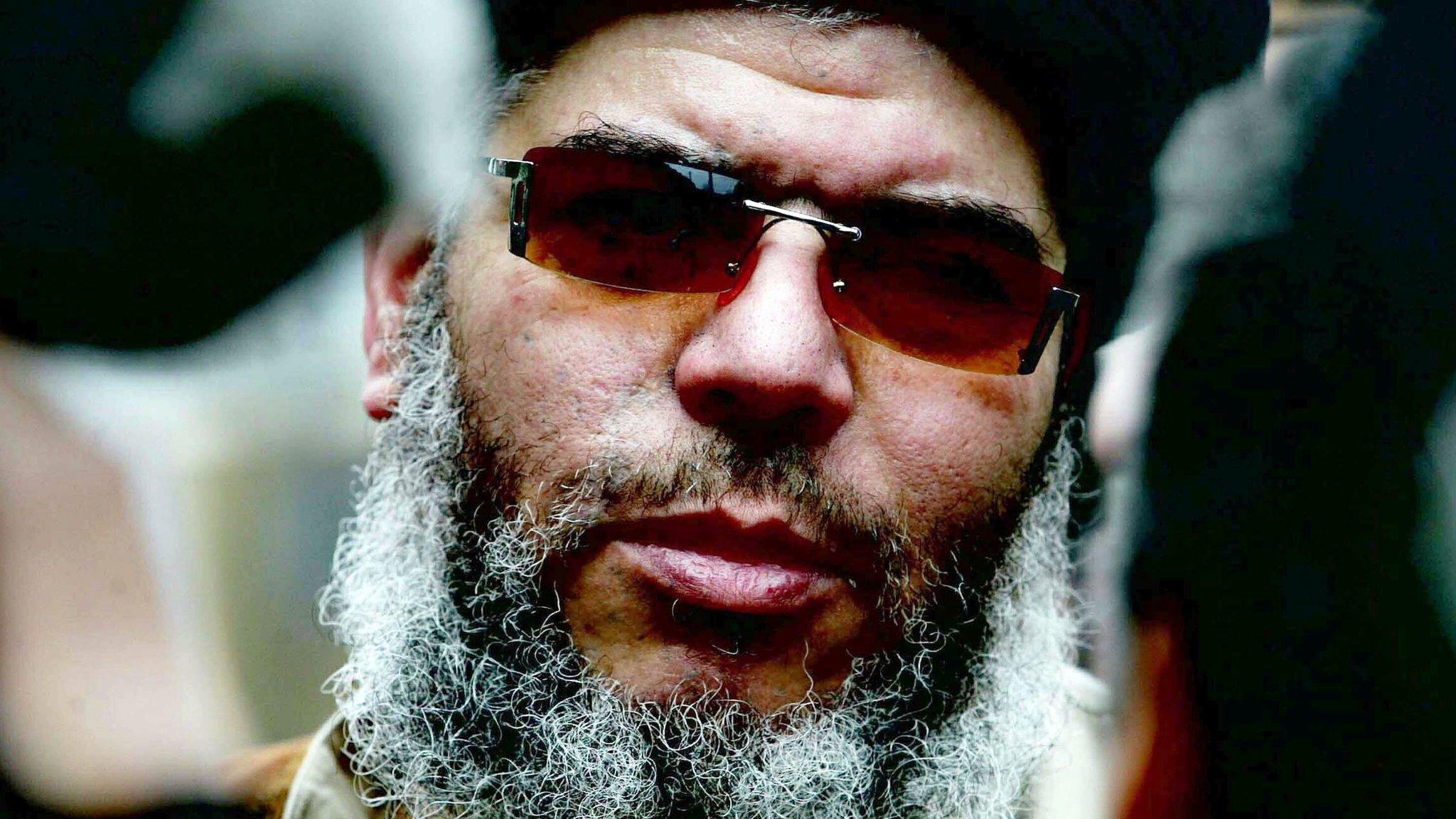

"He has nothing to lose," says Marc Sageman, the author of Leaderless Jihad. "He's got no arms and one eye missing. He's seen as a monster. He's Mr Hook."

In the courtroom, Abu Hamza is wearing drawstring cotton pants and a light-blue, V-necked T-shirt that fits loosely over his shoulders. His voice is husky, and his glasses are attached to a black cord that is slung over his shoulder.

When he talks, he bobs his head up and down. At times he licks the stump of his arm and turns a page of a document.

US officials asked for the extradition of Abu Hamza

He has a sense of humour. He says he changed his name in the UK, adding that the process was simple.

"You pay £25 ($40) and you write an application saying, 'I want to be John Travolta,' and you are John Travolta," he says.

Then he explains he did not really choose that name. The jurors smile.

He is also self-deprecating. He says people have exaggerated the part he played with the mujahideen in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

"Unfortunately the reputation is much bigger than the reality," he says.

He had only a bit part, he says: "Just a couple of bullets towards the communist regime". His past has been embellished in other ways, too.

"All sorts of stories," he says. "Some people say I went to Saudi Arabia and stole money, and they cut off my hands. The gossip never ends."

In fact, he says, he was working for the Pakistan army in Lahore in August 1993. Several men were trying to develop explosives that could be used by the military.

"They chose some cheap materials - benzene and nitrate," Abu Hamza says.

Abu Hamza is held in a jail across from the federal courthouse

Someone left a bottle with a detonator on a table and told him what to do if there was a problem. "He said, 'Just throw it in the bath,' and he left," Abu Hamza says.

"I looked at the bottle," he says. "Then I held it. I saw it getting hot, and I wanted to throw it to the bathroom. But someone was standing near the sink.

"It just went off," he says. "I was just looking at it - like this."

He hunches his shoulders and tilts his head, pretending to look at the device. "That's why I lost this eye."

Finally he describes his experiences in Bosnia, trying to assist people who had been affected by the war, in the 1990s. He describes the way people tried to help those in Srebrenica - and says UN forces blocked them.

"They would not let them in," he says.

In July 1995, more than 8,000 Muslim men and boys were killed in a massacre in Srebrenica.

He catches his breath, and his head slumps. He wipes his mouth with his stump, and the judge sees he is crying. She says they will have a short break.

If he is found guilty of the offences, he could be sentenced to decades in prison.

In the meantime, his evidence seeks to debunk myths about his role with the mujahideen and how he lost his hands, as well as notions about accused terrorists.

Through his testimony, he becomes a human being, says Karen Greenberg, director of the Center on National Security at Fordham University's law school, not a cartoon villain. In this way, he allows people in the courtroom to see him more clearly.

"He's not proselytising, he's not making speeches," she says. "He's talking about how he sees himself in the world of Muslim events in the last two decades.

"We know so little about the voice of a terrorism suspect. This opens up our eyes to who they are."

- Published9 January 2015

- Published1 May 2014

- Published5 October 2012