Bowe Bergdahl: A father's risky campaign

- Published

Robert Bergdahl's campaign for his son's release is considered unorthodox

Robert Bergdahl refused to stay quiet when his son, US Army Sgt Bowe Bergdahl, was kidnapped. Instead, he waged a daring and unorthodox campaign.

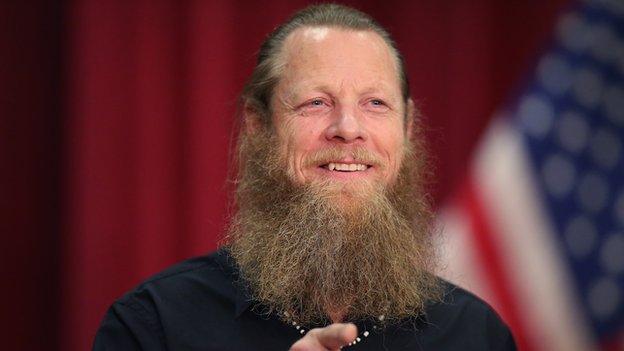

Standing next to his wife, Jani, at a press conference at the Idaho National Guard headquarters, Robert Bergdahl looked like a tribal elder - or as close as one can find in Boise.

He wore a beaded necklace and had a long beard. It was trimmed in a style that is popular among Haqqani militants, a group who had reportedly held his son captive in Pakistan near the Afghanistan border.

While his wife, Jani, spoke at the podium about their son, he tugged at his beard and fought back tears.

"I'm proud of how much you wanted to help the Afghan people," Bergdahl said, addressing his son directly.

He told the journalists in the room that central Idaho looks like Afghanistan, since both places have rugged mountains and harsh terrain. The land is beautiful and "heart-breaking", he said.

"It makes you tough."

For years his own toughness has been tested, as he watched Taliban-produced videos, external of his son. Then on Saturday, Bergdahl heard the good news directly from US President Barack Obama - his son was free.

People in Hailey decorated their town with signs and shrugged off criticism of Robert Bergdahl

Kidnappings have become a distressingly common occurrence over the past several decades, used by militants to raise cash or to send a political message.

Family members usually stay behind the scenes and hope that government officials, special forces or hired experts will help their loved ones.

"Families are told to keep things quiet because you don't want to upset the process," says Marvin Weinbaum, a former Pakistan analyst for the US State Department.

The kidnapping and release of Sgt Bergdahl has been marked by controversy, however, and by his father's forthright approach to the ordeal.

According to media accounts, Sgt Bergdahl left his military outpost in Afghanistan in June 2009 and then was seized by Taliban militants. Some call him a deserter. At this point, the full story of his kidnapping is not known.

Years ago, a military official told me that he and others were trying hard to get Bergdahl released, but that they could only go so far in their efforts.

"The US does not negotiate with kidnappers," he explained.

In fact, US officials were trying in private to hammer out a deal with the Taliban. Negotiations over Bergdahl went on for years, leading to an exchange - him for five Taliban detainees held at Guantanamo, a decision that has led to criticism from Republicans.

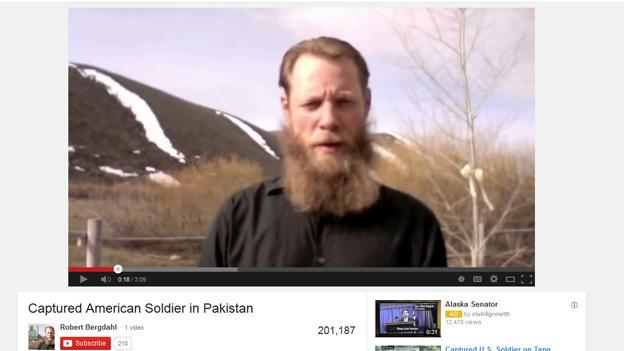

Even when kept under wraps, the discussions were delicate. Yet the father did not stay quiet. He spoke frequently with US officials - and with the Taliban, though indirectly. In a video, external released on YouTube in May 2011, he was shown in front of a mountain, thanking the Haqqanis and others "who have cared for our son".

It was part of a bold, and sometimes bizarre, strategy to get his son back.

"This man didn't play by the usual rules," says Mr Weinbaum. "Whether or not that actually brought about his son's release, you can't know for sure," he says. "But it certainly kept the sergeant at the forefront."

Robert Bergdahl hardly fits the profile of a high-stakes negotiator. He is an unusual man even by mountain standards, a culture that celebrates those who live "off the grid".

He lives at the end of a dirt road in Hailey (population 7,000), in a house crammed with books. For years he worked as a deliveryman for United Parcel Service.

"He is personable," says his friend Sue Martin, owner of Zaney's River Street Coffee House. Years ago she hired his son to make lattes.

Robert Bergdahl appealed directly to his son's captors via YouTube

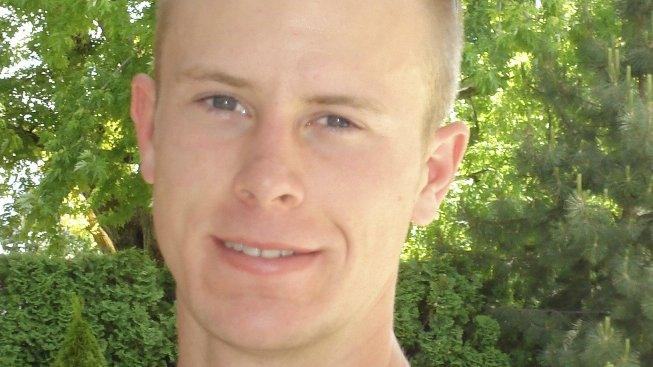

A photo of Sgt Bowe, clean-faced and serious in his army beret, now sits on the counter next to a jar of biscotti and a Magic 8 Ball, a toy that makes predictions. She says customers would pick up the Magic 8 Ball and all ask the same question.

"It was always, 'When is Bowe coming home?', not, 'Is he?"' she says. "There's not been a doubt expressed."

Today the town is filled with yellow balloons and signs that say "Bowe Is Free at Last". People here rallied behind Robert Bergdahl, even when he said provocative things.

After his son was seized, Bergdahl dove into a study of Pashto and the politics of the militants.

Last month he sent out a tweet directed to a Taliban leader, external saying he was "working to free all Guantanamo prisoners". He added: "God will repay for the death of every Afghan child."

His friends have tried to empathise.

"He's a dad," says Lance Stephensen, a member of a group called Boise Valley POW-MIA Corporation. Their motorcycles were parked outside the Idaho National Guard headquarters on Sunday. "Think of the pressure and stress."

Lance Stephensen (right) with brother Mark (middle) and Joel Robinson, has shown support for Robert Bergdahl

At the press conference Robert Bergdahl hinted at some of the struggles that he and others faced while they tried to get his son released.

"You'll never know how complicated this was," he said at the press conference.

Whether mistaken or not, Robert Bergdahl's rogue campaign ended well.

He told journalists that his son would soon go from Landstuhl Medical Center in Germany to an army medical centre in Texas to help him adjust to the US.

Then Bowe Bergdahl will head home.

- Published3 June 2014

- Published25 March 2015