Exhumed family vault reveals secrets of Washington history

- Published

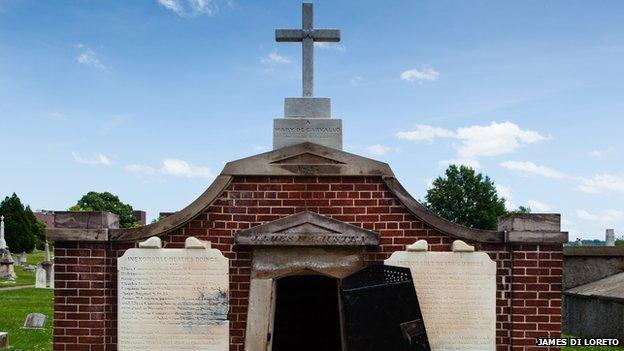

The Causten vault is located in the Congressional Cemetery in the US capital city

Exhuming the remains of a 19th Century family in Washington reveals clues about the way that people lived - and died - in the past.

All that is left of one of the most prominent families of 19th Century Washington are half a dozen plastic boxes containing human remains, an assortment of rusting coffin handles, and some personal effects such as rosary beads and scraps of cloth.

Death, the great leveller, has made the upper class almost indistinguishable from poor people of the time.

But scientists who exhumed the remains from the vault, which belonged to the Causten family, say that's not strictly true.

"This very well-to-do family gives us an example of what life was like in urban Washington compared to different classes in rural areas," says Doug Owsley, a forensic pathologist at the Smithsonian Institution. He is working on the project as part of renovations at Washington's Congressional Cemetery.

'Death a constant'

He says the Causten bones offer evidence of diet, lifestyle and disease during the Civil War era. This information can be cross referenced with historical records.

"That background history is powerful information for a scientist to help better read other remains we come across," says Dr Owsley, who recently discovered proof of cannibalism at the first English colony in Jamestown, Virginia. He is heading a study of 400 years of life in the Chesapeake region.

"I can see in the remains from this tomb, the first attempts at medical treatment, such as dental fillings that experiment with different types of metals.

"The fact that they have an elite lifestyle where they're not out digging ditches is clearly registered in the bones. I don't see the types of physical markings I see in somebody who has a more rigorous lifestyle."

But wealth couldn't protect the Caustens from their children's death.

"Death was a constant, infant mortality was at 50% - so odds were you would lose half your children," says Laurie Burgess, a social historian and anthropologist at the National Museum of Natural History.

Only the rich could afford this type of cast iron coffin exhumed from the Causten vault

In fact, it was the death of a child that prompted the building of the Causten family vault.

Little Charles Isaac Causten was almost two when he died on 8 August 1835. His body had to be stored in a public vault until construction of the family tomb was completed.

Others would join him, including a 14-day-old baby. His mother died immediately after giving birth.

'Distinct chronology'

This period also marked the beginning of the funeral industry, says Ms Burgess. Being rich and fashionable, the Caustens were among the earliest people to adopt the new style of ornate metal handles, name plates and decorations.

"The coffin hardware enables us to date burials. It follows a distinct chronology. In the first half of the 19th Century you don't find much, but around 1850 the emerging trend of decorating coffins kicks in," she says.

Cast iron caskets were another innovation. Two such coffins were recovered from the vault - one of which held the remains of a three-month-old baby.

"They are a pure reflection of the wealth of the family," says Dr Owsley. "In the 19th Century when a wooden coffin could be made for a dollar and a half or two dollars, these children's coffins are going to be very expensive - they might be $35."

.jpg)

Eliza and James Causten commissioned the family vault after their infant son died in 1835

A metal plate over the head could be slid open and the face of the deceased viewed through glass. The viewer would be protected from any infectious disease such as smallpox that the person may have died from, but still identify the body.

The Causten vault was also built during the Rural Cemeteries Movement, when graveyards began to be landscaped to imitate bucolic country settings.

"Right now we live in a period where we're always at arm's length from death - but this was a time when that wasn't the case," says Ms Burgess. "There was a whole period in the 19th Century when death would be characterised as sleep and it was heavily romanticised."

The Causten vault is one of a dozen that have been restored at Congressional Cemetery, the final resting place of many noteworthy Americans. These include a vice-president, 84 senators and congressmen and the first director of the FBI, J Edgar Hoover.

And the descendents of the Causten family remain influential in the US today. The great-great grandparents of Tim Shriver, the president of the Special Olympics and a relative of President John F Kennedy, are buried in the vault.

He attended a special re-interment of the Causten remains.

"For me it's a chance to connect to my family and to remind them that their legacy lives," he says.

"But it's also the poignancy and repeated deaths of small children. When you see the remains there, one after the other, how many of our ancestors had to live with that as a fact of life? That to me was quite moving."