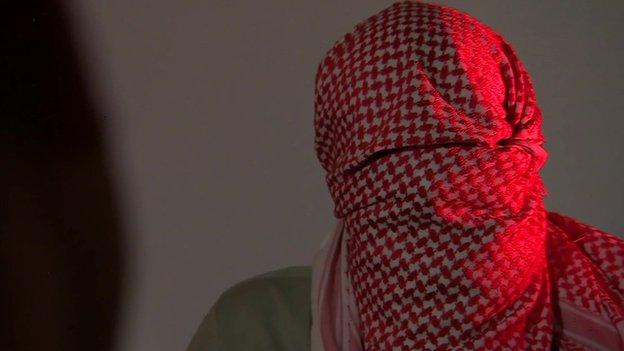

Following a dangerous path to radicalisation in Syria

- Published

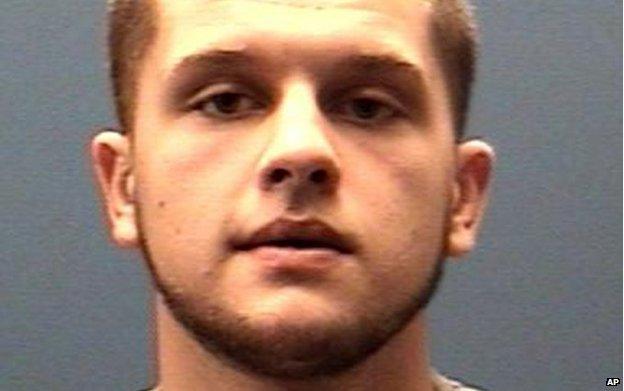

Douglas McAuthur McCain was reportedly killed in a battle in Syria

Douglas McAuthur McCain went to Syria, one of the many Americans who have taken part in the civil war, and died while fighting alongside Islamist militants. How did he and other Americans make their way to the battleground?

About 100 US citizens have gone to Syria to battle the government of President Bashar al-Assad, according to Matthew Olsen, director of the US National Counterterrorism Center.

That's a far lower number than in some European countries, like France and the UK.

Some of these Americans have ended up dead. Besides McCain - who grew up in Minnesota - Nicole Lynn Mansfield, and Moner Mohammad Abu-Salha were also killed in Syria.

Mansfield, 33, was a convert to Islam from Flint, Michigan. She died last year - apparently during an attack on Syrian government forces. Abu-Salha, a 22-year-old from West Palm Beach, Florida, joined the rebel group Nusra Front and became a suicide bomber on 25 May.

Each of these cases is unique, and the Americans who go to Syria come from different parts of the US. In addition they choose a life of violent extremism for a variety of reasons, many of which are known only to themselves.

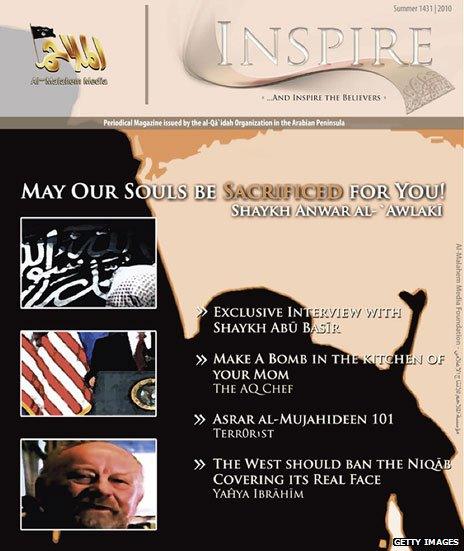

A cover story in Inspire magazine was called "Make a bomb in the kitchen"

Yet on a basic level they tend to follow a similar path. Here's a look at the some of the steps they take on their way to extremism.

Aspiring jihadists are like most people in the US. When they are trying out something new, they look to the internet for help. There is a wealth of material for them.

A radical cleric, Anwar al-Awlaki, who was killed in a drone strike in Yemen in 2011, spoke fluent English - and edited a magazine called Inspire. Boston Marathon bombing suspects Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev reportedly looked at the magazine and later made their own explosive devices.

More recently Islamic State supporters published an English-language magazine called Dabiq, external. (People also refer to the group as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, as well as the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant or Isil.)

The flashy graphics are designed to appeal to a broad audience. One issue featured pictures of black flags and militants manning checkpoints.

Moner Mohammad Abu-Salha was the first American suicide bomber in the Syria conflict

Sometimes these individuals, whether they live in the US, UK or other countries, also shop online.

Two men, Yusuf Zubair Sarwar and Mohammed Nahin Ahmed, who are from Birmingham, UK, bought the book Islam for Dummies - then went to Syria, according to the New Statesman, external. They later pleaded guilty to terrorism charges.

Most people who make the journey to Syria seek help, often from people they meet online. Many of the relationships start on Twitter.

"The ISIS recruiter will start to groom the person," says Humera Khan, executive director of Muflehun, external, an organisation that tries to counter violent extremism.

"Once that person seems interested, the conversation moves off Twitter," she says. "They use email and Skype."

They may also look for guidance from those who've gone before them - and made videos. Abu-Salha made a video, external before his suicide.

Aspiring jihadists aren't the only ones online, though. People who work for the US state department tweet, external messages that cast Islamic State militants in a bad light, hoping to convince people not to sign up with them.

Turkish airports - here is one in Izmir - provide a stopping point for many foreign fighters

"Fighter's father calls #ISIS barbarians - son starred in recruitment video, was killed in #Syria," one of the officials wrote, external.

UK officials have also been fighting online extremism. Writing in the Sunday Telegraph, external, Prime Minister David Cameron said they have removed "28,000 pieces of terrorist-related material from the web, including 46 Isil-related videos".

Istanbul is a popular destination for aspiring jihadists, whether they live in the US or Europe. "It's pretty easy for people to travel to Turkey - to say, 'We're going on a vacation'," says Ronald Sandee, a former analyst with the Dutch military intelligence service.

One American, Eric Harroun, chose that route, travelling first to Turkey and then Syria. He was indicted by a federal grand jury on charges related to his involvement with one of the militant groups in Syria. Earlier this year he died of an accidental drug overdose, according to his family.

Foreign fighters in Syria - by the numbers:

3,000: Tunisia

250: Belgium

120: Netherlands

400: UK

Source: Foreign Fighters in Syria by Richard Barrett, Soufan Group

Harroun is not the only one who chose Turkey as a transit point.

A Texas man, Michael Wolfe, 23, planned to fly Iceland Air to Copenhagen and then go to Turkey. Afterwards he wanted to go to Syria to commit "violent jihad", according to court papers, external.

He unknowingly relied on an undercover FBI agent for travel advice, though. He was arrested on 17 June at Houston airport. He later pleaded guilty to attempting to provide material support to terrorists.

If the Americans make it to Turkey, though, the journey becomes easier.

"'They'll say, 'OK, I'm here,' and someone will come and find them," says Khan. Others will take a bus to a place near the Syrian border. "Then they make their way in," she says.

The journey from the US to Syria - and the decision to join an extremist group known for beheading people - may seem chilling to some. These Americans see things differently. Sandee says: "They think that Syria is heaven."

- Published8 July 2014

- Published15 October 2013

- Published15 August 2014

- Published1 September 2014