Ebola crisis: Five ways to break the epidemic

- Published

With the worst-ever outbreak of Ebola revealing woefully inadequate health systems in West Africa, especially in those countries recovering from civil war, the international response and leadership of the World Health Organization (WHO) has also come in for criticism.

Announcing US plans, President Barack Obama said the outbreak was "a threat to global security" which required a "global response".

So, what would bring the epidemic under control? Here are five things officials say would help:

1) More treatment centres

All agree this is key as the real number of cases is believed to be much higher than the 4,366 recorded.

Victims in Liberia - the country worst-affected by Ebola - are spreading the virus, some dying on the streets, because there is not enough room at isolation clinics set up to treat infected patients.

President Obama's plan to send 3,000 troops to build 17 healthcare facilities and train health workers has been met with some relief, especially in Liberia where most of this deployment will go.

But it may take weeks before the first US beds are operational, and the WHO has confirmed that there are no free beds anywhere in Liberia at present.

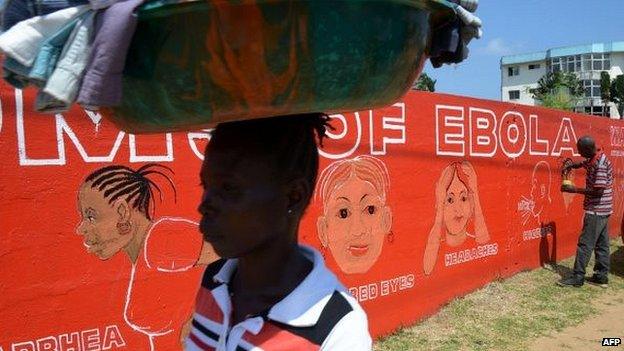

People with Ebola symptoms in Liberia cannot get beds in centres dealing with the virus

The aid group Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) has urged other countries to "deploy their civil defence and military assets, and medical teams, to contain the epidemic".

Last week, the UK announced it would set up a 65-bed treatment centre for infected medical staff in Sierra Leone, and France has put a team of about 20 experts on rotation to Guinea.

But Philippe Maughan, who works for Echo, the humanitarian aid branch of the European Commission, thinks MSF's expectations may be too high.

"If it thinks there is a sort of foreign legion ready to deploy for this outbreak, there isn't," Dr Maughan says.

"Ebola is a very specific virus for which even specialists in infectious diseases are not necessarily skilled."

2) Home care

Until promised treatment centres are set up, this will be the best attempt to stem infections - especially in Liberia.

Under broad medical supervision, affected communities would learn how to provide basic care using rehydration and painkillers.

"It won't be possible without the participation of the community," warns Tarik Jasarevic, a WHO spokesman.

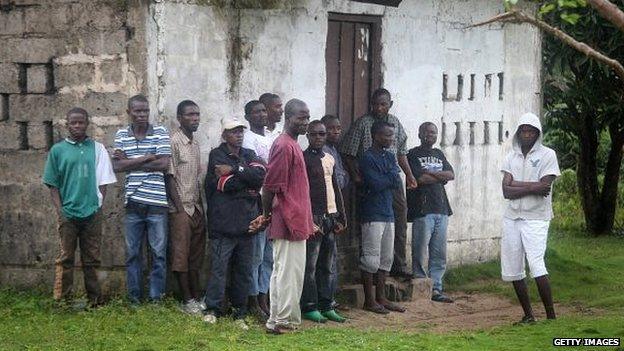

Gaining the trust of fearful communities is key

This will include breaking down the fear of people wearing protective suits. But it is a risky move.

"The need in personnel to have this work is big; supervision and discipline are key," says Dr Maughan.

"Some will fail and some will work. It's not ideal, this is a last resort."

MSF warns it will only work in the early stages of treatment.

"As soon as their family member shows more severe symptoms, like bleeding, they will seek to bring them in a treatment centre anyway," says Brice de la Vigne, MSF's director of operations.

3) Air bridge and medevac system

Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, the worst-hit states, have been isolated because of flight bans and borders being shut - despite WHO recommendations to the contrary.

It has dealt a blow to their economies and food security will soon become an issue.

Blockades and closing borders is hurting local economies

Aid agencies are lobbying states to grant them humanitarian corridors.

President Obama has promised to develop an air bridge to get supplies into affected countries faster.

Senegal, where many UN agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have their regional offices, is expected to become a logistical hub.

The authorities there have officially agreed to it but, sources say, remain reluctantly slow in turning the theory into practice.

"I understand the concerns from the Senegalese government; Ebola was brought to Nigeria by an airline passenger after all, but we need to get equipment in these countries and we need to get staff in and out," Dr Maughan says.

The evacuation of infected medical staff is also an issue, potentially limiting volunteers.

4) Preparation elsewhere

Don't wait until there is a confirmed case to get ready and make sure what looks good on paper can work on the ground, is the warning to countries in the region.

When it arrived in Nigeria, people were spooked, one diplomat told the BBC.

"If the CDC (Centre for Disease Control and Prevention) hadn't sent 50 experts to Nigeria, they would not have it under control," Dr Maughan says.

Medical kits are now being dispatched throughout the region and some countries have started public awareness campaigns.

Ebola-awareness campaigners were at schools in Abidjan on the first day of term this week

Medical agencies believe that if there are more cases in Senegal, where 67 people are still under surveillance after coming into contact with an infected Guinean student, the outbreak could be quickly stopped.

But concerns remain over the capacity to act quickly in countries most at risk - Mali, Guinea-Bissau and Ivory Coast.

"We are working with the authorities in Mali to get all the 86 health centres and hospitals we sponsor there ready," says Alexis Smigielski, head of the Dakar-based medical charity Alima.

5) Vaccines

At least two experimental vaccines are looking promising and could be made available in West Africa in November if trials are conclusive.

Injections would be given to medical staff as a priority.

"It holds quite a lot of hope," says Dr Maughan.

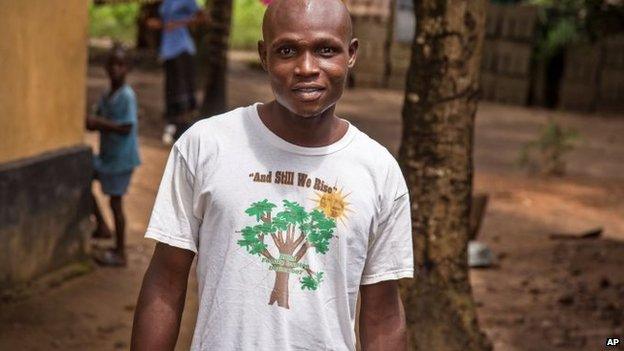

With supportive care, patients can survive - like this man in Sierra Leone - and their blood may help treat others

However, it could take several months to reach a production that would respond to the scale of demand.

The WHO has also indicated that people who have survived can now provide blood to treat patients who are sick.

But the UN health agency has warned that current lab experiments should not distract from the actual needs on the ground.