As goes Colorado, so goes the nation?

- Published

- comments

For 10 years Colorado has tilted steadily to the political left, as Democrats have claimed victory after victory. Now Republicans are pinning their hopes on a campaign that could ensure they gain control of the US Senate - and prove that their party has a future in an increasingly urban, socially liberal nation.

Driving east from Denver, the Rocky Mountains disappear into the haze. The land flattens into rolling plains, dotted by farms, ranches and the occasional expansive cattle or pig feed lot, which can be smelled before they're seen.

Although this is still Colorado, it seems a different state from the capital city metropolis. And, politically, it might as well be.

Yuma Mayor Shad Nau says Cory Gardner embodies his town's conservative values

While Colorado has trended Democratic in the past 10 years, in little towns like Yuma, population 3,500, a rock-ribbed conservatism remains the order of the day. Government is an unwelcome intruder, and the land is not a recreation, it's a resource - to be ploughed, grazed or drilled.

Yuma is the kind of place where the mayor is also the proprietor of a local hardware store, and he can say with a straight face that he doesn't like getting involved in politics. At a local bar, most patrons give full-throated voice to their conservatism, and those who disagree do so apologetically.

Colorado's Fourth Congressional District - which covers the eastern portion of the state and is home to towns like Sterling, Fort Morgan and Yuma, which barely make it onto maps - voted 59% to 40% in 2012 for Republican Mitt Romney over Barack Obama. The president won the state as a whole by a 51% to 45% margin.

Cory Gardner is the Fourth District's representative in Congress and a Yuma native. He's a fifth-generation Coloradan who was first elected in 2010 and represented the area in the statehouse prior to that. His father runs a tractor dealership, as his grandfather did before him.

According to Yuma mayor Shad Nau, Mr Gardner embodies the town's conservative values.

"He's from a good family, and he's well thought of," Mr Nau says.

Now Mr Gardner has his sights set on higher office, challenging first-term incumbent Democrat Mark Udall for one of Colorado's two US Senate seats.

Option two

Recent polls suggest the Udall-Gardner race is a statistical dead heat, external, although Mr Gardner appears to be gaining momentum. It's a worrying development for Udall supporters, as the senator's seat is one his party can ill afford to let slip away.

There are too many places where incumbent Democrats are on the ropes. With a third of the Senate up for election this year, their party is playing defence. South Dakota, West Virginia and Montana are all but lost. Alaska, Arkansas, Louisiana, Iowa and North Carolina are in jeopardy. The opportunities for Democratic pickups - Kansas, Georgia and Kentucky - range from improbable to the remote.

Six seats have to change hands to give Republicans control of the upper chamber of Congress. Colorado voters could hold the keys to power.

More than that, however, this contest is being viewed by the national Republican Party as a test case for whether traditional rural conservatives like Mr Gardner can still win state-wide elections in places, such as Colorado, that seem to be slipping out of their grasp.

Following their electoral defeat in 2012, Republicans nationwide were faced with a choice. They could ascribe their defeat to some of their more controversial policy stances or lay the blame on an inability to sell those positions to the general public.

Initially, it appeared the party leaders were opting for the former. In a study, external released by the Republican National Committee in March 2013, a group of senior Republicans, including former Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour and White House press secretary Ari Fleischer, said their party needed to embrace issues like immigration reform and moderate their position on gay rights, while moving away from being the party of rich plutocrats.

Mr Gardner, however, represents option two. His 84% rating from the American Conservative Union places him among the Congress's more right-tilting members. He differs from past Colorado Republican candidates more in style and emphasis than substance.

Congressman Cory Gardner is trying to tie his opponent to an unpopular Democratic president

In the charismatic, quick-witted Mr Gardner, Republicans think they have found a new face for their party - a candidate who won't make the kind of political fumbles, such as an ill-thought-out reference to "legitimate rape", external, that have cost conservatives winnable seats in previous elections. They also think they've learned from past mistakes in how the run their campaigns and spend their money.

"The Republican Party believes in education reform, believes in jobs and economic growth, believes in opportunity and the value and the dignity of every single individual," says Colorado Republican Party chair Ryan Call. "Our party has not always put great candidates on the field that embody and represent these values."

With slightly over a month until election day, it's not long until Republicans find out whether Cory Gardner is the answer.

A liberal enclave

If Cory Gardner is a product of Yuma, Mark Udall also embodies the spirit of his hometown, Boulder.

About 150 miles west of Yuma, Boulder seems a world away. Surrounded by mountains and trees, the college town is populated by professors, ex-hippies, white-collar professionals and outdoor enthusiasts.

Pearl Street, a pedestrian promenade that runs through the centre of town, is lined with coffee shops, boutiques and bookstores.

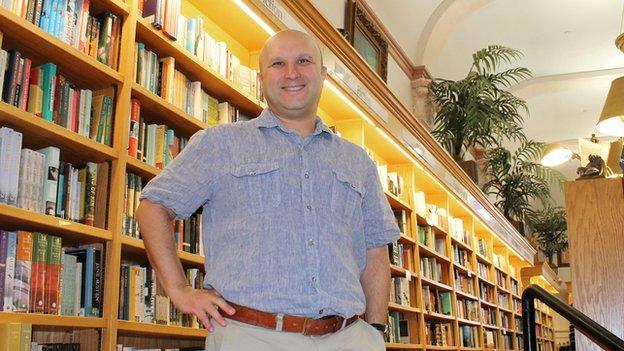

Arsen Kashkashian, the general manager of Boulder Book Store, says the town's residents are reliable liberals who prize the outdoors and the steps their elected officials have taken to preserve the environment.

Book store manager Arsen Kashkashian says that Boulder residents believe in the good government

"We've seen government work here," he says. "We have these great outdoors because we've had the government buying open space for 40 years."

Prior to being elected to the Senate in 2008, Mr Udall represented Boulder in Congress for 10 years, and Mr Kashkashian says his sponsorship of environmental legislation keep him popular there.

For decades Boulder, Colorado has purchased preservation land around the city - but with limited space available for building construction, the city faces an affordable housing crisis.

The son of a long-time member of Congress from Arizona, Mo Udall, Mark Udall moved to Colorado after college and spent 20 years leading Outward Bound, a company that sponsors outdoor activities for children and teens.

Where Mr Gardner is short and occasionally dishevelled, Mr Udall looks like a classically handsome Western politician. Tall, grey-haired, with steely blue eyes, he boasts of having climbed the 100 tallest mountains in the state.

The race sets up a battle of contrasts. The Boulder progressive versus the plains conservative. The Western political royalty versus the small-town hero.

According to the political forecasting website 538.com, external, the ideological divide between the two candidates is the largest of any competitive Senate race.

The war for women

Like most congressional races that take place in years between the presidential elections, the Udall-Gardner contest is decided by which candidate can best give their sometimes unenthusiastic party faithful a reason to vote.

Mr Gardner has tried to rile up his supporters by tying Mr Udall to an unpopular Democratic president, whose Colorado approval ratings hover in the mid-40s.

He's criticised the senator for saying the Islamic State is not an "immediate threat" to the US, and has called for him to support construction of the Keystone XL oil pipeline from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico.

Footage shows desperate attempts of locals to flee the flooding, as Alastair Leithead reports

He has also tried to undermine Democratic efforts to motivate their political core constituencies, emphasising that he's pro-environment, including conservation as one of the "four corners" of his campaign platform, in addition to economic growth, energy independence and education reform.

Mr Udall, on the other hand, is trying to paint his opponent as a conservative extremist. At a meeting with outdoor sports enthusiasts in Denver last week, he said Mr Gardner supported selling public lands to raise federal revenue. He called it "mortgaging our future".

"In the end for me, this is about protecting a really special way of life," he said. "We're here, yes, to work and provide for our families. But we're also living in Colorado, we want to get our families into the back country, we want to have a chance to explore and enjoy mother nature because of what it teaches us and the way we feel."

In a recent television advert, external, the senator also accuses Mr Gardner of conspiring with fellow congressional Republicans to shut down the government last fall, hampering federal recovery efforts for flooding that struck the mountain hamlet of Jamestown the previous month.

Mr Udall also is attacking Mr Gardner for supporting federal legislation that he says would outlaw abortion and make certain types of birth control illegal. Mr Gardner has backed a way from previous support for a similar Colorado ballot initiative, saying "it was the wrong thing to do", but remains a sponsor of the congressional legislation.

The BBC speaks to women in Colorado about what issues matter to them ahead of the mid-term elections.

Perhaps as a way of diffusing the issue, Mr Gardner has endorsed a proposal to make oral contraception available without a doctor's prescription. It's a move he says will reduce costs, but it has been attacked on the left as a way to undermine Mr Obama's federal healthcare reform support for free contraceptives covered by insurance.

"They are overplaying their hand," says Dick Wadhams, former chair of the Colorado Republican Party. "Despite six months of this one-issue pounding, Cory remains deadlocked or possibly even a point or two ahead. Cory's introduction of the contraception-with-no-prescription issue I think has been effective in blunting the main Udall-Democratic abortion attack that Cory wants to ban contraception."

Branding an opponent as being dismissive of the concerns of female voters, which liberals have labelled a conservative "war on women", comes from a campaign playbook that has worked effectively for Colorado Democrats in the past. In 2010 - another mid-term year in which Democrats faced challenging political headwinds - incumbent Senator Michael Bennet successfully painted his opponent, Ken Buck, as extreme on women's issues.

Senator Mark Udall says Cory Gardner supports selling public lands

Mr Buck made a joke about not wearing "high heels and skirts" during his primary race against a female opponent, and Mr Bennet hammered him relentlessly for it. The Democrat ended up carrying the women's vote in his race by a 56%-40% margin.

According to Republican strategist Kelly Maher, however, these "uterus issues" are losing their effectiveness.

"How many times do people have to scream at you that you're not going to be able to get the pill?" she asks. Eventually, she says, voters will respond: "Eh, I don't think that's true."

Amy Runyon-Harms, executive director of the liberal activist group ProgressNow Colorado, counters that Mr Gardner has a track record of being an anti-abortion extremist, despite his recent moves to the political centre.

"He's trying to reinvent himself to the point that he's almost lying about some of his positions to con the voters of Colorado into thinking he is something he is not," she says.

A winning ground game

Ten years ago Colorado Democrats achieved what had seemed impossible - at least to their conservative counterparts. They ended 40 years of Republican control of the state legislature and began a decade-long trend of liberal control of Colorado politics.

In 2006 they elected Democratic Governor Bill Ritter and have held the office ever since. Mr Obama won the state in 2008 and again in 2012. The steady leftward trend was punctuated only briefly by Republicans retaking the state House of Representatives in 2010 - a development that was reversed in 2012.

Groups like Ms Runyon-Harms's ProgressNow Colorado - independently funded, independently operated interest groups that co-ordinate with like-minded activists - have received much of the credit for this change of fortune. Funded by deep-pocketed, left-leaning backers, the groups have invested heavily in what political operatives call the ground game - voter identification, outreach and data collection - as well as mainstream media campaigns.

The latest data-crunching technologies have allowed campaigns to target individual voters's interests and concerns. Colorado progressives revolutionised the process - what they termed the "Colorado miracle" - and it was successfully implemented on a national scale by Mr Obama's campaign team in 2008 and especially 2012.

The Colorado progressive groups have also made a point of blanketing opponents with relentless, often negative advertising attacks.

Ms Maher says a decade of Democratic victories have thinned the ranks of Republican candidates suitable for higher office.

"We were getting steamrolled," she says. "They were taking out our young promising candidates at the city council level, at the school board level, at the state house level."

It has meant some of the same faces have resurfaced time and time again in Colorado Republican politics. For instance their nominee for governor, former Congressman Bob Beauprez, ran for the same office unsuccessfully in 2006.

For the coming elections, however, conservatives insist that they've closed the gap.

When Republican National Committee chairman Reince Preibus visited the Denver area last week, he specifically highlighted his party's efforts to improve its outreach and voter targeting - and admitted just how bad things had gotten for conservatives, both in Colorado and nationally.

"You can craft policies all day long up here, but if you don't have a conduit in the community, telling people what it is you believe in, then the numbers aren't going to move," he says.

ProgressNow Colorado's Ms Runyon-Harms is yet to be convinced.

"Progressives have consistently outworked conservatives when it comes to the ground game," she says. "I don't see it changing in 2014. It hasn't been proven to me yet that they know how to do it effectively. It doesn't matter if you're knocking on more doors if your message is wrong."

Rebirth or dead end?

A successful political strategy works right up until when it doesn't. Colorado Republicans had a winning formula up until 2004. On the national level, George W Bush strategist Karl Rove predicted a permanent Republican majority - only a few years before Mr Obama swept to power.

Republicans believe the tide is about to shift in Colorado once again - returning the state to its rightful shade of Republican red, in the words of Mr Beauprez.

A win would encourage Republicans to believe they've found a way to succeed in today's political environment; that the demographic shifts in Colorado aren't a death sentence for their party's national prospects.

Ms Maher says there's a fight for the "heart and the soul and the future of the Republican Party". Colorado is a harbinger of things to come, she says, and if conservatives don't adapt across the country, they're headed for defeat.

"Colorado is always a few election cycles ahead of everybody else," she says. The 2004 Democratic wave in the state presaged Mr Obama's success.

"What happened in Colorado is coming for you," she tells fellow conservatives in other states. In places like Virginia, North Carolina and even Texas, conservatives have to be prepared - or be ready for the kind of rude awakening she and her colleagues experienced 10 years ago.

BBC Pop Up: Mobile bureau reporting from across the US

If Colorado is in fact the future, a Cory Gardner win could be an indication that the kind of conservative he represents - a small-town, rural candidate who places an emphasis on independence, self-sufficiency and limited government - still has a future.

If he and many of his fellow conservatives lose, it will be at least two more years in the wilderness for the mountain state Republicans - and an ominous sign for 2016, when the presidency is at stake and conservatives will have to defend their own crop of vulnerable Senate seats.

Over the next six months, a team of BBC journalists will explore US, setting up a mobile bureau for a month in six very different regions of the country. This month, they are based out of Boulder, Colorado. For more information, visit BBC Pop Up online.