Hard times for area where Johnson's War on Poverty was launched

- Published

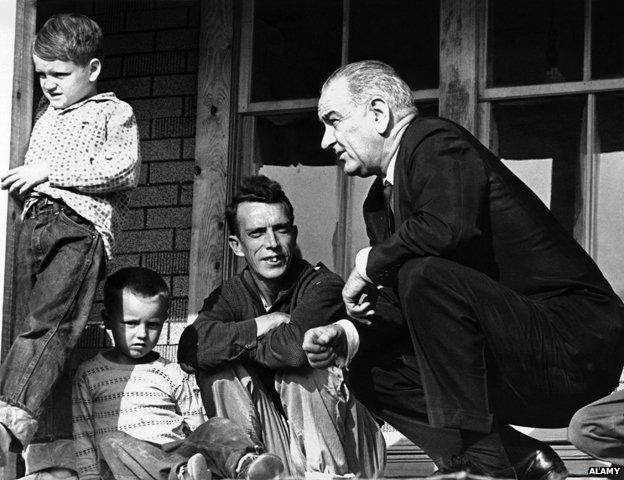

In 1964 the War on Poverty was declared from a porch in a troubled corner of Kentucky. Fifty years on, the community still faces deprivation.

History was made on Calvin Fletcher's front porch, but he rather wishes it hadn't been.

Calvin is the son of Tom Fletcher, the unemployed sawmill operator and father of eight who unwittingly became the face of President Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty.

When the poverty tour rolled into Inez, Kentucky in 1964, LBJ visited the Fletchers' simple brown cabin, nestling in the Appalachian Mountains, and heard of his struggles to find work in a either the timber or coal industry which, even then, was struggling.

"The president's visit was the worst thing that ever happened to the family," Calvin says bluntly. "Since then we've had nothing but people wanting to talk about that day and taking photos of this house."

The house remains much as it was back in 1964, a rather dilapidated structure in beautiful surroundings - a testament to the Fletcher family's hard life.

Tom Fletcher's old cabin today in Inez, Kentucky

Although Tom re-trained as a car mechanic, he became ill and ended up drawing a disability allowance. There was tragedy, too. His second wife was convicted of murdering their two young children.

He died in 1994, a symbol not of the success of the War on Poverty, but of its limits.

Calvin didn't want to speak about himself or his father, but it was clear that life hadn't turned out well for him, either.

A few miles away in Warfield, I meet a family member with a more positive view of the events. Tom Fletcher's daughter-in-law Delsie Fletcher works for the Head Start programme that was established in 1965 as one of the battalions fighting the war on poverty.

War on Poverty

.jpg)

Launched by President Lyndon Johnson (pictured) in 1964

Legislation included the Equal Opportunities Act, the Food Stamp Act and the Social Security Act

Resulted in programmes including the Neighborhood Youth Corps, VISTA, Head Start, the Job Corps, Upward Bound, and the Community Action Program

It provides young children from low-income families with educational, medical and nutritional support - and it's still needed. The White House pledged an extra $500 million (£312 million) to Head Start this week.

"I would have been honoured to think the president kicked off the war on poverty on my porch, "Delsie tells me in the cabin in a school car park where Head Start has its office. "But the Fletchers were really embarrassed by it. Everyone saw them as the poorest family in the county."

Delsie Fletcher works for the Head Start programme in Warfield, Marin County, Kentucky

What about the policy itself?

"I think the war on poverty is being fought every day," she says, without hesitation. "I have parents coming in every day asking for food. And if we have to pull the money out of our own pockets, we'll go get the food for the families."

Earlier this year, The White House marked the 50th anniversary of the War on Poverty by launching a policy of Promise Zone - five impoverished regions that would qualify for special government aid if they showed they were willing to help themselves.

One of those zones is in south-east Kentucky, but Inez falls outside it. On the evening I spent there, I saw how local people were taking their own initiatives to fight one of the underlying causes of poverty - poor education.

In the gym of Inez community hall, a black-hatted witch was reading the Charlie Brown Halloween classic The Great Pumpkin to a circle of enthralled pre-school children, dressed in an array of comic book costumes, from Captain America to Donald Duck. It was a Love to Read event - a child literacy evening sponsored by a local shop.

The "witch", a teacher called Kristen Hale, explained how hard it was to convince the town's older children that they need new educational skills: "A lot of students are still saying they're going into coal. They haven't grasped that it's declined and is coming to an abrupt halt. They still have the mindset that coal will always be there."

Two hours south, in Clay County, they don't have that complacency problem. Last year, only 54 people there were employed by the once-dominant coal industry.

In the county seat, Manchester, it's estimated that as many as half the residents have to travel to other towns to find jobs. That makes it quite a challenge to keep people in a region ranked the hardest place to live in the United States in a New York Times study earlier this year.

Margy Miller isn't shrinking from the task, though. Apart from her work in Manchester city hall, she runs the Stay In Clay organisation. As the name suggests, its goal is to persuade the young generation not to leave.

Much of her work consists of trying to make the place look more attractive - from putting a pumpkin and flower display outside her office to painting murals on empty walls. She's also encouraging people to tell true folk stories in the local theatre. This is not an attempt to preserve a way of life, but to save a community from extinction.

.jpg)

Margy Miller shows James Coomarasamy a mural in Clay County, Kentucky

"There's something about being raised in the hills that you're used to the horizon, that you feel protected," she says proudly. "It's our home and we love it."

But, fifty years on from the war on poverty, does she feel she's getting support from the state or the federal government?

"Not really," she sighs. "They don't really know how to help us. We feel like the forgotten people."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.