Canadian mum flouts cannabis law for treatment

- Published

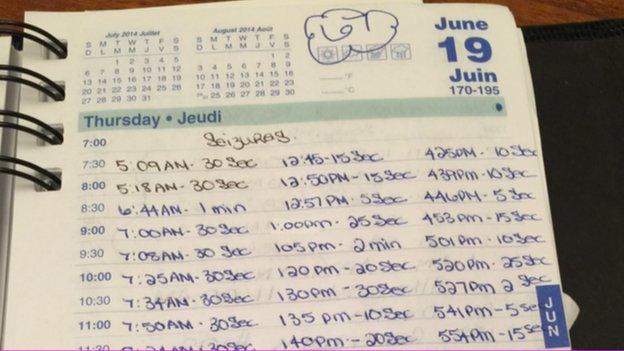

Liam has had far fewer seizures using cannabis oil

The mother of a boy with severe epilepsy refuses to give her son his medical marijuana in the form the law dictates he should get it - through smoke or vapours.

Six-year-old Liam McKnight is always the first in his family to run to the door. His mum Mandy says he loves to see who is visiting.

The McKnight family, in Ottawa, Canada, has a constant flow of people coming through the house - between members of their daughter's dance community, and the many therapists - speech therapists, physiotherapists, listening therapists - who come to visit Liam.

Liam has Dravet Syndrome, a severe form of epilepsy. But after debilitating seizures and pharmaceutical trials and errors throughout his life, Liam is doing much better, now that he is on a medical cannabis oil regimen.

In June of this year, the day before Liam began using the oil (made from a particularly effective strain of marijuana), he had 67 seizures.

In the 10 days after, he had one.

The problem is, Liam's treatment is criminal. Using medical marijuana is legal in Canada, but only in the dried form that can be smoked or vaporised. That, says Mandy, is not realistic for such a young child.

"Who's going to expect a six-year-old to smoke weed?"

As early as 2001, Canada approved the use of medical marijuana, allowing people with severe conditions to use the drug to ease symptoms.

But there haven't yet been clinical trials to prove oil is safe to use so there's a restriction limiting patients to the use of dried medical marijuana.

In 2012, the British Columbia Supreme Court struck down this restriction.

The province's high court gave the federal government one year to change the law. Instead, the government appealed against the ruling.

In August of this year, the BC Court of Appeal ruled in agreement with the BC Supreme Court. Within a month, the federal government appealed against the decision again, taking the case to the Canadian Supreme Court, which means the restriction still holds today.

Mitch Earleywine, a researcher in addictions at University of Southern California, says smoking cannabis poses risks that are absent in other forms of medical marijuana.

"Unfortunately, smoking - lit, burning material - does release some respiratory irritants," said Mr Earleywine.

"Oil doesn't have the rapid onset that [vaporising or smoking] would have, but there's no data suggesting ingesting oil is any less safe."

Liam is not developmentally capable of using a vaporiser, and Liam's mum says his dose can be more accurately measured in oil form.

After Mandy McKnight wrote to the government of her family's predicament, Health Minister Rona Ambrose responded in a letter dated 1 August.

"I am sorry to learn of Liam's struggles with epilepsy. I can understand how this would have a profound impact on you and your family.

"To date, no marijuana oil product has been authorized for sale in Canada," Ms Ambrose wrote, adding any researchers interested in a clinical trial should contact Canadian officials.

Health Canada responded to the BBC's inquiry with a similar response.

"The risks and benefits of using unapproved marijuana products (e.g. salves, oils, creams made with extracts) are unknown," Sara Lauer, a spokeswoman for Health Canada, wrote.

Parents in the US with severely epileptic children are turning to cannabis for treatment. The BBC went to Colorado, the US state which has legalised the drug, to meet the self-described 'marijuana refugees'.

Earlier in November, New Democratic Party MP and health critic Libby Davies appeared with Mandy on the Canadian Broadcast Corporation's news show Power & Politics, explaining current legislation and Parliament's committee report Marijuana's Risks and Harms - a committee Ms Davies sits on - that points to holes in Canada's law.

"We have a government that's focused on an ideological position when it comes to marijuana, instead of a realistic pragmatic evidence-based position marijuana," Ms Davies said.

Ms Davies has been supportive of her family, asking Parliament to amend regulations and allow edibles for kids like Liam.

There are at least nine families using medical marijuana oil to ease Dravet symptoms in Canada, says Patti Bryant, chair of Dravet.ca, a Canadian network for families dealing with Dravet.

In the Unites States, the laws surrounding the use of medical marijuana vary by state. In Michigan, the laws are similar to Canadian law. In New York, smoking is not allowed.

"In recent years, the trend has been to have more variety available to patients, but it depends on the state," said Karen O'Keefe, director of state policies at the Marijuana Policy Project in the US. "There isn't a ton of clinical research."

Many families move to states where access is legal, says Ms O'Keefe, and over 12,000 American families are on a waiting list for a strain of medical cannabis oil that treats children without the classic high of marijuana.

But while the laws support the use of medical marijuana in 23 states and the District of Columbia, these have not met the needs of all families.

Last month, Minnesota mother Angela Brown was charged for medicating her son with cannabis oil. She faces up to two years in prison and $6,000 (£3,800) in fines.

The use of medical cannabis oil was approved under Minnesota law in May, but the law does not come into effect until July 2015.

Medical marijuana laws vary in the United States

With the risks in mind, Mandy McKnight says breaking the law is a concern for her family.

"Am I scared that I'm breaking the law? Yes, I am. But I'm more scared for Liam if we don't. I'm scared if we don't do anything, what would happen to him."

Within the family's Dravet Syndrome support group 14 children died last year, she says.

"Cannabis was a last resort for us. We don't have time to wait for clinical trials."

So, every day at dinner, Liam eats about a tablespoon of cannabis mixed with coconut oil.

- Published7 May 2014