A muted Thanksgiving in Ferguson

- Published

Churches in Ferguson tried to brighten this Thanksgiving in the troubled suburb

Thanksgiving is the most family-centred festival in the American calendar, yet in riot-hit Ferguson, Missouri, it was a muted celebration.

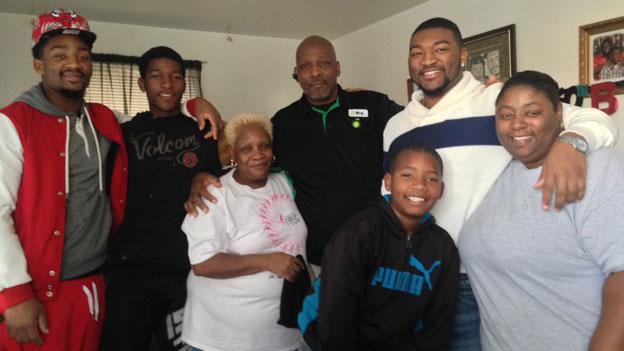

"Family is always first," says Pretrail Wyatt, 39, a single mother of six boys, who is celebrating Thanksgiving in Ferguson with her sons, her father and her aunt.

The family has gathered in the house that used to belong to her grandmother on a quiet street on the outskirts of the suburb.

This is the first time they are celebrating the holidays without their grandmother, who bought the home 30 years ago. She died in January last year and the family acutely feels her loss.

"I've cooked so much I've forgot half the stuff" says aunt Carolyn Rolland, 56. "I made sweet potato pies and just a lot of stuff my mom usually cooked for the holidays."

Joining the celebration is Ron G, 23, one of Pretrail's six sons. The boys were brought up without a father and Pretrail is immensely proud that Ron, like his brothers, has graduated from high school.

O'Marion flanked by brother Ron G on left and Darion on right

One family, one meal, three generations

In fact, Ron has gone further, finishing a qualification in communications from community college. He now works as a rapper and this year performed in Chicago and New York.

But earlier this week, he was back in Ferguson, on the streets with the protesters.

"I'm a part of the youth, 90s generation. As a man I feel I have morals and principals I stand for," he says. "It was necessary for me to be out there."

Rajini Vaidyanathan met one family as they celebrated Thanksgiving in St Louis

His mother, Pretrail, disagrees. "I kept calling him and texting him to make sure he was ok," she says. "I support them protesting, but I don't support them burning up businesses. That's people's jobs, their livelihoods."

Mother and son both feel the decision not to indict Officer Darren Wilson for the shooting of the unarmed teenager, Michael Brown, was unjust.

"I think they need to get these shady prosecutors out of there, I think they need to get rid of the shady police," says Pretrail.

The scars from the riots were still evident on Friday

But they differ on the method of protest. Pretrail says she has not joined one of the marches, not even in August right after Michael Brown was shot.

"I'm kind of on the fence with that one, because like my mom said, it's people's livelihoods," says Ron. "But in the same sense, there's no greater way to send a message. We want reparations, we want things to be done immediately of these things will continue to happen."

From the kitchen comes the sounds and smells of Thanksgiving dinner being prepared.

Pretrail's aunt, Carolyn has been cooking since Tuesday, concentrating on the food and not the drama unfolding on the streets nearby.

Carolyn remembers when her family was the first black family to move into what was, 30 years ago, a predominantly white neighbourhood.

"It's gone downhill since then," she says. "When other black families starting moving in, the police stopped patrolling here. They abandoned us."

Despite being able to move into the more affluent white neighbourhood, the family has seen hard times.

The family gathered at their grandmother's home

Ron G remembers growing up with his brothers when his mother was at work and unable to look after them.

"We would make meals out of anything - just one stick of baloney and a packet of noodles," he says.

"We'd cut up the baloney really small and share it out between six of us, then we would put a sheet of newspaper on the ground and sit on it to eat."

But those hard times are now over and this Thanksgiving, the kitchen table is loaded up high with Carolyn's lovingly prepared dishes.

With her mother's death this year, her brother Ronald Williams, 60, is now the oldest family member.

Carolyn has made his favourite food, honey glazed ham and noodles with meatballs, to help make up for her mother's absence.

"Being around as long as I've been around, I feel it has got better for black people to some degree," says Ronald who wears his uniform from his job as an attendant at a BP petrol station.

Pretrail was worried that her son was on the streets of Ferguson for the unrest

He remembers a time when he was young when he could not leave his black suburb without being harassed, beaten up or called names.

"Racism still exists. It's just shown differently to what it was shown when I was younger," he says. "They tried to hide it more now than bluntly put it out there. But if it didn't exist, we wouldn't be having the problems that we have."

Despite not taking to the streets to protest, his daughter Pretrail agrees.

"The police are going to stereotype my kids because they're young and black. They're going to grab them before they grab the white boy," she says.

The family nods in agreement. But even though they all feel targeted by the police, their youngest member O'Marion, 11, says he wants to become a cop when he grows up. "I just want to try to help people and that is kind of it," he says.

Although his brothers tease him, O'Marion tries to talk to policemen whenever he sees them.

"I feel safe but sometimes I feel scared because I don't know if those police are good police or bad police," he says.

As the family continue their preparations for dinner, O'Marion's grandfather Ronald quietly says that he will try to talk the boy out of his ambition.

The older man does not agree with the violence on the streets or the methods the protesters have been using, but he still thinks there is a war going on.