Why Texas is closing prisons in favour of rehab

- Published

The US is known for its tough criminal justice system, with an incarceration rate far larger than any comparable country. So why is it that Republicans in Texas are actively seeking to close prisons, asks Danny Kruger, a former speechwriter for David Cameron.

Coming from London to spend a couple of days in Texas last month, I was struck most of all by how generous and straightforward everyone was.

Talking to all sorts of different people about crime and punishment, the same impression came across: We expect people to do the right thing and support them when they do. When they don't we punish them, but then we welcome them back and expect good behaviour again. It's not naive, it's just clear.

For years that straightforward moral outlook translated into a tough criminal justice system. As in the rest of the US, the economic dislocations of the 1970s, compounded by the crack epidemic in the 1980s, led to a series of laws and penal policies which saw the prison population skyrocket.

Texas, for instance, has half the population of the UK but twice its number of prisoners.

Then something happened in 2007, when Texas Republican Congressman Jerry Madden was appointed chairman of the House Corrections Committee with the now famous words by his party leader: "Don't build new prisons. They cost too much."

The impulse to what has become the Right on Crime initiative was fiscal conservatism - the strong sense that the taxpayer was paying way too much money to fight a losing war against drugs, mental ill-health and petty criminality.

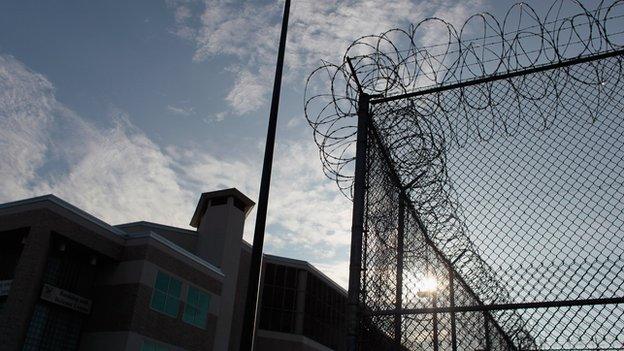

The Right on Crime inititative has seen three prisons close

What Madden found was that too many low-level offenders were spending too long in prison, and not reforming. On the contrary, they were getting worse inside and not getting the help they needed on release.

The only response until then, from Democrat as well as Republican legislators, was to build more prisons. Indeed, Mr Madden's analysis suggested that a further 17,000 prisoners were coming down the pipe towards them, requiring an extra $500m (£320m) for new prisons. But he and his party didn't want to spend more money building new prisons. So they thought of something else - rehab.

Consistent with the straightforward Texan manner, the Congressional Republicans did not attempt to tackle what in Britain are known as "the causes of crime" - the socio-economic factors that make people more disposed to offend. Instead, they focused on the individual criminal, and his or her personal choices. Here, they believe, moral clarity and generosity are what's needed.

Though fiscal conservatism may have got the ball rolling, what I saw in Texas - spending time in court and speaking to offenders, prison guards, non-profit staff and volunteers - goes way beyond the desire to save money.

The Prison Entrepreneurship Programme, for instance, matches prisoners with businesspeople and settles them in a residential community on release. Its guiding values are Christian and its staff's motives seem to be love and hope for their "brothers", who in turn support the next batch of prisoners leaving jail.

The statutory system is not unloving either. Judge Robert Francis's drugs court in Dallas is a well-funded welfare programme all of its own - though it is unlike any welfare programme most of the 250 ex-offenders who attend it have ever seen.

Clean and tidy, it is staffed by around 30 professionals who are intensely committed to seeing their clients stay clean and out of jail, even if that means sending them back to prison for short periods, as Judge Francis regularly does when required.

Every week the ex-offenders attend court and take a drugs test. Then, in the presence of 50 of their peers, they tell the judge what they've been up to before receiving a round of applause from the crowd.

Graduates of the 2014 Prison Entrepreneurship Program receive their certificates

Immediate, comprehensible and proportionate sanctions are given for bad behaviour, plus accountability to a kind leader and supportive community. This is the magic sauce of Right on Crime.

Far from having to build new jails for the 17,000 expected new inmates, Jerry Madden and his colleagues have succeeded in closing three prisons.

I visited one by the Trinity River in Dallas, now ready for sale and redevelopment. They spent less than half the $500 million earmarked for prison building on rehab initiatives and crime is falling faster than elsewhere.

This, then, ticks all the boxes - it cuts crime, saves money and demonstrates love and compassion towards some of the most excluded members of society. It is, in a sense, what conservatives in America and Britain dream of - a realistic vision of a smaller state, where individuals are accountable for their actions and communities take responsibility for themselves and their neighbours.

It is a more positive version of the anti-politics - anti-Washington, anti-Westminster - tide that seems to be sweeping the West.

I hope that Right on Crime will catch on in Britain. Already there are positive steps towards establishing drugs courts, expanding rehab and opening up our prisons to the community groups which can make such a difference.

This is part of a major reform of outsourcing - some call it privatisation - of prisons and probation, which involves handing huge contracts to private companies who will, it is hoped, subcontract to the little guys.

The danger is that people distrust big corporations as much as they distrust central government. The ideal is a criminal justice system that is genuinely community-led - not directed by profit or by politics, but by local people and the professionals accountable to them.

Danny Kruger is a former speechwriter for David Cameron and now runs Only Connect, a charity for young people involved in, or at risk of, crime.

Republican Rehab broadcasts on BBC Radio 4 on Monday 1 December at 20:00 GMT - or catch up online.