Viewpoint: Ferguson and a new civil rights fight

- Published

The civil rights movement in the 1960s fought unjust laws. Can a modern movement brought on by the events in Ferguson, Missouri, take on a more ambiguous target? Journalist Ellis Cose examines the modern struggles of those protesting for racial equity.

We have been here far too many times - police confront black males, something goes horribly awry, and racial tensions roil the nation. All that changes are the details.

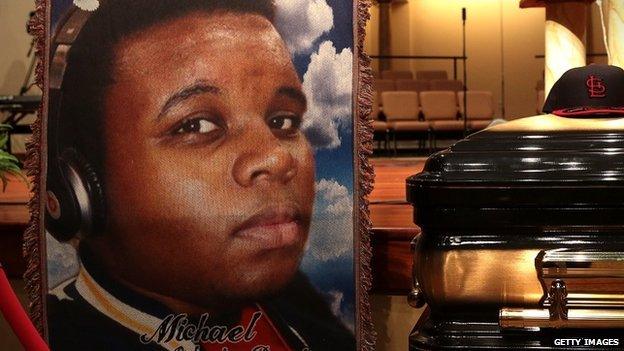

In this case, Michael Brown ended up dead as his companion ran in fear. Always, in the aftermath, there is agony and confusion as a community rises up demanding change that never fully comes.

Over the past half century or so, we have seen the pattern repeated countless times. So many of the riots of the 1960s - those uprisings that came to characterise the so-called long hot summers - were set off by encounters between police and civilians of colour. Those incidents continue to occur all too frequently, and all too frequently they end in death.

The journalism group ProPublica recently revealed that young black men were 21 times, external more likely than young white men of being gunned down by police.

Brown's father (centre) has called for peace, but he is also more likely to be stereotyped as aggressive

One obvious reason for the disparity is that blacks are more likely to live in high-crime neighbourhoods; so law enforcement officials are especially likely to feel threatened and therefore to draw their guns. An even more obvious reason is that black youths are more prone to be perceived as hulking brutes.

The election of Barack Obama gave rise to much talk of a post-racial society, of an America where blacks, Latinos, and other people of colours were no longer judged or hindered by race. There is something to that notion. Yet we continue to perceive race and racial differences in the same way we perceive differences - and make judgments - about other aspects of appearance and status. As a number of studies have made clear, external, even when job applicants present exactly the same credentials whites tend to be preferred.

This is not to say that race always rules. If someone looking like Barack Obama happened to be walking down a city street, virtually no police officer would see him as a threat worth shooting. His expensive suit and middle-aged status would merit a measure of deference. But for a young black man in casual clothes on a dark street in a presumably dangerous neighbourhood, reality would be quite different.

This country has a history of endowing such men with an almost mythical aura of menace.

To get some sense of how this plays out, one need only review the grand jury testimony of Darren Wilson, who defended killing Michael Brown by describing Brown as an inhuman, unstoppable beast. "It looked like he was almost bulking up to run through the shots, like it was making him mad that I'm shooting at him."

This stereotype of the hulking black brute, impervious to pain, capable of crushing strong white men with a single slap of his massive hand has been with us for a very long time.

More than a century ago, Clifton R Breckinridge, a former congressman who had been President Grover Cleveland's minister to Russia, observed that the black race was "the most negative and tractable of which we have any considerable knowledge" and went on to declare, "When it produces a brute, he is the worse and most insatiable brute that exists in human form."

What should Ferguson mothers tell their children?

Much as things have changed in America - and they have changed hugely since that analysis was published in 1900 - the image of the hulking, menacing black brute still haunts us; and it is getting young black men killed.

As rational human beings, we need to attack that stereotype with the same resolve and determination that Officer Wilson brought to his encounter with Michael Brown. Perhaps the protests spawned by Brown's death and Wilson's grand-jury exoneration are a sign that some among us are prepared to do just that.

But this movement is much more complicated than the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

What it shares with that movement is a sense that we have arrived at a moment when something has to change. Brown's death, after all, did not occur in a vacuum. It occurred on the heels of several arguably unjustified killings of black men by police or self-declared enforcers of order. Eric Garner was killed in Staten Island after being caught selling untaxed cigarettes. Trayvon Martin was shot by a gun-toting vigilante simply because he seemed suspicious.

Protests in Washington, DC, continued days after the grand jury decision in Ferguson

Bloody Sunday, in which a civil rights march in Selma, Alabama, culminated in a police riot, led directly to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

It would be great if this movement could bring about something similarly concrete.

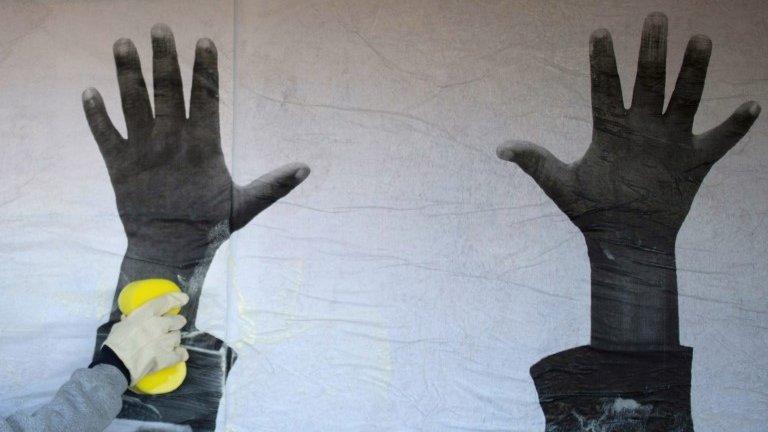

But how do you legislate against stereotypes, against people, some of them with uniforms and guns, acting on poisonous perceptions? Rather than the mid-century civil rights movement, this new movement is more akin to (and, indeed, can be seen as allied with) the Occupy Wall Street movement, or the anti-mass-incarceration movement.

It is a growing and collective howl of outrage raised against some things that are seriously wrong in the American system.

That outrage, I like to believe, is registering in some deep part of the American consciousness and will ultimately lead to self-healing.

But unfortunately, this sickness has no immediate remedy.

Ellis Cose, author of The End of Anger: A New Generation's Take on Race and Rage and numerous other books, is currently writing a memoir.

- Published1 December 2014

- Published27 November 2014

- Published18 June 2015

- Published26 November 2014

- Published24 August 2014