Why interrogators prefer the soft approach

- Published

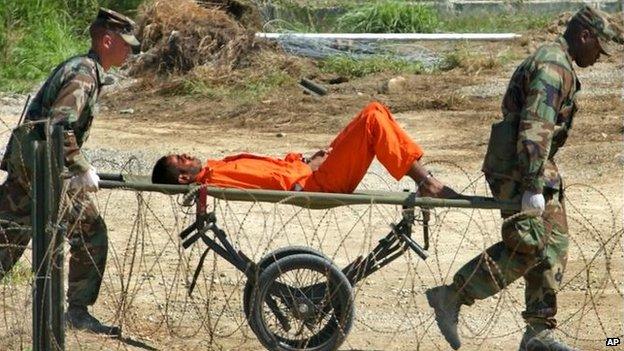

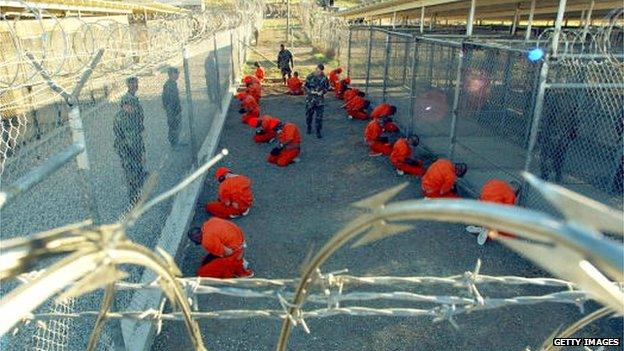

Guantanamo Bay was one of many sites where captives were interrogated harshly

Amidst the appalling catalogue of abuses, mistakes and oversights committed by the CIA on detainees in the early 2000s, one thing stands out in the Senate Intelligence Committee's report like a beacon.

"At no time did the CIA's coercive interrogation techniques lead to the collection of imminent threat intelligence, such as the hypothetical ticking time bomb," says the report.

In other words, all that mistreatment, all those hours of waterboarding, of dragging people hooded and shackled, up and down corridors, depriving them of sleep for days on end and subjecting them to white noise, did not actually yield any real information that stopped a terrorist attack.

Not true, says the CIA's current director, John Brennan. In a riposte to the report, he said: "Our review indicates that interrogations of detainees on whom Enhanced Interrogations Techniques were used did produce intelligence that helped thwart attack plans, capture terrorists and save lives."

Wasted days

But the Senate committee spent five and a half years going through a staggering six million pages of documents. They did not reach these conclusions lightly.

The CIA's brutal interrogations did produce results, but they were frequently false leads. Humans, like animals, will do anything to make extreme pain stop.

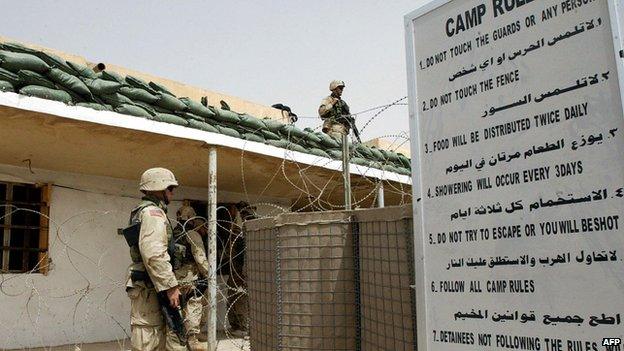

Suspects captured by the US military were passed on to CIA interrogators

Countless days and dollars were wasted, on top of the distress suffered by detainees, as CIA investigators chased worthless leads given out in extremis by desperate prisoners.

Unlike some of the hapless Afghan civilians who ended up in Guantanamo Bay by mistake, or were sold to US agents by unscrupulous middlemen, the men the CIA held in their "black sites" were in many cases dangerous, hardened terrorists.

Some did hold key information in their heads and in the case of men like Abu Zubaydah, al-Qaeda had reportedly trained them to resist interrogation.

Hungry for affection

So was there a better way for the US government to acquire this information without risking breaking international law and committing a moral outrage?

Yes there was. Talk to almost any trained British army interrogator and they will tell you that in the long run it is the "logical friendly approach" that yields the best results.

This does not mean treating the prisoner like some precious VIP. An experienced British army interrogator, who questioned high-value Iraqi POWs, says when a detainee is seized, often as a result of a violent struggle or firefight, there is the inevitable shock of capture and the fear of what is going to happen to them.

Often they imagine the worst - remember the Royal Navy sailor who broke down in tears when he and his crew were captured in the Gulf by an Iranian patrol boat and briefly held in 2007.

"They are hungry for affection," says the former interrogator about prisoners he questioned. "Eventually, they will be willing to co-operate in exchange for safety and comfort."

Many interrogators believe that a gentler approach can yield the best results

It does not work every time but there are numerous documented cases of both military prisoners and suspected terrorists being actually relieved to "unburden" themselves of information, thereby ensuring their own safety and relative comfort.

But this approach, of course, takes time and patience and judging by the Senate committee's report, the CIA deployed some totally unsuitable people for the task.

"The CIA deployed individuals without relevant training or experience," it said. "CIA also deployed officers who had documented personal and professional problems of a serious nature - including histories of violence and abusive treatment of others."

Even the two outside contract psychologists lacked "any experience as an interrogator, nor did either have specialised knowledge of al-Qaeda, a background in counter-terrorism, or any relevant cultural or linguistic expertise".

With such blunt instruments in their armoury, it is little wonder the CIA's interrogation programme appears to have gone so badly astray.

- Published9 December 2014

.jpg)

- Published9 December 2014

- Published9 December 2014