Senate CIA report sheds light on Washington

- Published

US Senator Dianne Feinstein said CIA officials provided inaccurate information about an interrogation programme

A Senate report exposes details about a covert interrogation programme run by the CIA. It also shows how secrets are kept, and revealed, in Washington.

Dianne Feinstein, a California Democrat who heads up the Senate Intelligence Committee, spoke on Tuesday on the Senate floor. This committee oversees the CIA, and agency officials are required to tell committee members about their activities.

Yet she said the CIA officials misled her and others about the interrogation programme, keeping it a closely-guarded secret.

The real story is more complicated.

Then-CIA Director Michael Hayden said that Senate committee members were briefed about the programme

In Washington a secret is something you tell one person at a time. It's a joke, with some truth. The CIA's interrogation programme, for example, was a badly-kept secret.

People all over Washington knew what was going on. Condoleezza Rice, as President George W Bush's national security adviser, said she would "not object", according to the report, external.

Others at the White House followed suit.

As the report revealed, Mr Bush was not told where the CIA prisons, or black sites, were. In this way, he wouldn't inadvertently reveal their locations.

He may not have known the details. But like others in Washington, he knew the broad outlines of the story.

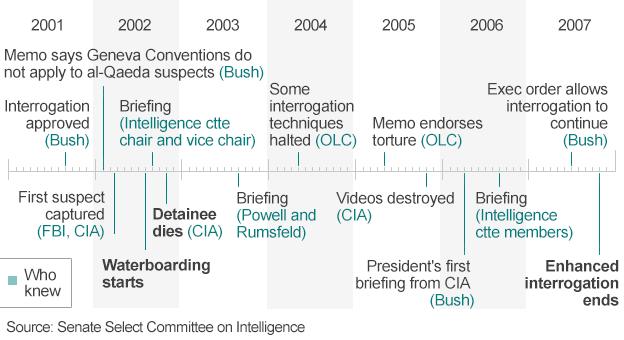

OLC is the Department for Justice Office of Legal Counsel

John Rizzo, who served as the CIA's chief legal officer, once told me about the way White House officials were worried about al-Qaeda in the months following the attack.

In this climate of fear Mr Rizzo and other CIA officials were grappling with the prospect of conducting interrogations for the first time in the agency's history.

Mr Rizzo paved the way for the harsh interrogations by ensuring they fell within the parameters of the law. He did it in the way a lawyer does: He got it in writing.

Between 2002 and 2005 the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel lawyers wrote several memos about interrogations, saying the methods could not be described as torture.

Mr Rizzo did more than ask for legal opinions, though. He was deeply involved in the interrogations.

In one instance he was on the phone with a Justice Department lawyer, asking for permission for methods such as "walling" so interrogators could push a detainee against a wall - stopping short of burying a detainee alive only because the lawyers could not confirm the technique was legal. (That would take more time).

Yet these were not the actions of a madman or the work of a rogue agency. They were official policy, done at the behest of the president.

Still as the report makes clear the CIA officials were not as forthcoming as they could have been.

In the spring and summer of 2002, shortly after a terrorism suspect, Abu Zubaydah, was captured in Pakistan, they did not tell members of the committee about their plans for his interrogation.

In September the CIA officials briefed committee members. When the members later asked to visit the black sites, though, the CIA "rejected this request", according to the report.

In addition the CIA kept things from people, including Secretary of State Colin Powell. "Powell would blow his stack if he were to be briefed," wrote Mr Rizzo in a July 2003 email, as Ms Feinstein said.

But as the report showed, CIA officials did reveal information about the programme. They spoke with people in Washington, including committee members and journalists.

One CIA officer said he thought it was better to stay quiet, according to the report, but it was a bit late for that.

Campaigners, such as this one in Lithuania , have pushed for more information about the CIA programme

"I don't like so much talk about EIT's," he said in a 2005 email, referring to the "enhanced interrogation techniques. "But that particular horse has long left the barn."

For these reasons it is hard to support the argument that the programme was administered entirely in secrecy. Some journalists published stories about the programme, relying in part on accounts by CIA officers. Other journalists knew about the programme but, for a variety of reasons, did not publish accounts.

Many of the people in Washington who knew about the programme under the Bush administration did not condemn it strongly during those years.

One thing is clear, though. The conflict between CIA officials and Senate committee members made things more difficult at a time when they should have been working together to protect the nation.

Mr Rizzo, who has since retired from the CIA, said he believes agency officials, as well as committee members, should be more accommodating, as he wrote in Politico, external.

Ms Feinstein said top CIA officials have mis-characterised the way committee members saw the programme.

According to the report, then-CIA Director Michael Hayden said: "every committee member was 'fully briefed,' and that 'this is not CIA's programme. This is not the president's programme. This is America's programme.'"

People at the White House knew what the CIA was doing. So did people in Congress, as well as lawyers and journalists.

For better or worse Mr Hayden was right. As the report shows, the programme belonged not to a single institution - but to the nation.