State of the Union: How Obama changed over six speeches

- Published

Six years of speeches: President Obama from 2009 to 2014 (clockwise from top left)

Exactly six years after his inauguration, President Barack Obama offers Congress and the nation another State of the Union address. A look at these annual speeches reveals the rising and falling fortunes of the president's tumultuous time in office.

As Mario Cuomo, the two-term governor of New York who died earlier this month, once said: "You campaign in poetry. You govern in prose." If so, Mr Obama's 20 January, 2009, inaugural address was the final speech of the historic 2008 presidential campaign, emphasising hope and opportunity over specific policy goals.

"On this day, we gather because we have chosen hope over fear, unity of purpose over conflict and discord," Mr Obama said from the steps of the US Capitol. "On this day, we come to proclaim an end to the petty grievances and false promises, the recriminations and worn-out dogmas that for far too long have strangled our politics."

In an address to a joint session of Congress Mr Obama made a month later - a State of the Union in all but name - the president made a more workman-like effort, setting a tone and style he would largely follow in all of his congressional addresses. He talked of the need to rebuild the economy, then in the midst of a severe downturn, and touted the $787bn [£518bn] stimulus spending law the Democratic-controlled Congress had just passed.

In those early months of his presidency, Mr Obama was at the height of his power. With approval ratings in the mid-60s and sizable majorities in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, he and his party firmly controlled the levers of power.

During his February speech the president laid out an ambitious agenda. He endorsed financial regulation reform, an overhaul of the nation's health insurance system and a cap-and-trade plan for regulating greenhouse gasses. He also pledged to end the US war in Iraq and close the Guantanamo Bay detention centre.

Mr Obama again addressed Congress in September of 2009 to help push healthcare reform through Congress, but by his first formal State of the Union Address in 2010, storm clouds were on the horizon.

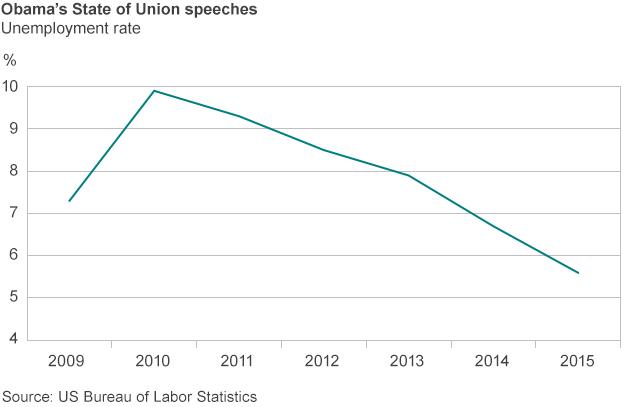

The public was wary of the increasing budget deficits and an economy that was still reeling. While the recession had officially ended in June 2009, the unemployment rate wouldn't come down from its peak of 9.9% until April 2010. The president pledged a government spending freeze and cuts to unaffordable or unnecessary programmes.

Although later that year the Democrats narrowly passed healthcare and financial sector reform, it would be the last legislative achievement for Mr Obama's party. Cap-and-trade was all but dead, and Republicans blocked action on Guantanamo. The grass-roots conservative Tea Party movement was growing in strength, and it would sweep Republicans to control of the House of Representatives in the 2010 mid-term elections

The president's next two State of the Union addresses, and a September 2011 address to Congress on jobs legislation, would be more reactive in nature. His proposals would remain largely unpassed.

After winning re-election the president in his 2013 State of the Union address called for an increase in the minimum wage, more funding for college education and climate change legislation. The speech was dominated by talk of firearm regulation, however, on the heels of the attack that left 20 children and six adults dead in a Newtown, Connecticut, elementary school.

With Republicans still in control in the House, however, none of these policy items would become law.

By his 2014 State of the Union address, the president seemed resigned to the fact that none of his legislative priorities would be endorsed by Congress. His approval ratings had sunk to new lows, thanks in part to a botched rollout of the healthcare.gov website the previous autumn.

The president's speech focused primarily on things he could accomplish without congressional approval, such as limited immigration reform and greenhouse gas regulation. The "unity of purpose" the president spoke of in 2009 seemed a distant memory.

Critics say President Obama is less keen on working with Congress

Now, exactly six years after his first inaugural address, the president - his dark hair now generously peppered with grey - speaks to the US people, and Congress, again. For the first time in his presidency, thanks to his party's rout in the 2014 mid-term elections, he faces a legislature wholly controlled by his political opponents.

Perhaps counter-intuitively this development may more clearly define the president's remaining power. Where over the past four years he could count on the Democratic Senate to snarl Republican plans hatched in the Republican House of Representatives, the chance that legislation he finds unappealing reaches his desk is now considerably greater.

He may finally find it necessary to wield one of the most powerful weapons in the presidential arsenal, the veto.

The president's standing with the American people may be on the upturn, as well. His approval ratings have rebounded from the lows that helped seal his party's fate last year. The employment rate continues to decline, reaching 5.6% in December.

The US Capitol in Washington where Obama will address both houses of Congress

The president is now fully on the defence in Congress, but he appears willing to counter-punch, with revamped proposals to make higher education more affordable and reform the tax structure. Whether it makes any difference to how the Republicans go about their agenda over the next year remains to be seen, however.

The reality is that this likely is the last real chance the president has to use a high-profile speech to put his imprint on US politics and policy. He has one more State of the Union address to give, in January 2016, but by then the race to succeed him in office will be in full swing. Both parties will be in the midst of choosing new standard-bearers, and legislative action will grind to a halt.

By then all eyes will be focused on the identity of the next person who will speak to the nation from the steps of the Capitol.