Netanyahu win gives Obama a headache

- Published

Israeli Prime Minister's election victory means more headaches for the Obama administration

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's election victory provides a headache for the White House, writes PJ Crowley.

President Barack Obama had hoped that an alternative remedy might help him alleviate some of the Middle East pain he and his administration have felt in recent months.

Alas, the test results are back - the pain is not going away and will actually become more acute and more difficult to manage during his remaining time in office.

A major source of the pain is well established - Mr Obama's problematic relationship with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who pulled out a hard-fought electoral victory and appears to have the inside track to form a new Israeli government.

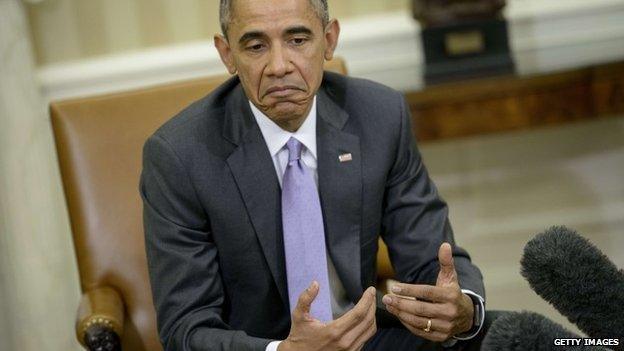

Mr Obama did not meet Mr Netanyahu during in Washington trip, citing the closeness of the election

The campaign produced complications that will undermine a crucial pillar of American policy in the Middle East, but in a different area than was anticipated just two weeks ago.

Heading into the elections, the foremost issue for Israeli voters appeared to be the rising cost of living and expanding gap between rich and poor.

Beneath the surface was the palpable tension between the Israeli prime minister and the US president, as well as its implications for the US-Israeli relationship and the broader region.

US media reaction on Israeli election

The New York Times' opinion page harshly criticises, external Mr Netanyahu's last-minute moves in the campaign - "Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's outright rejection of a Palestinian state and his racist rant against Israeli Arab voters on Tuesday showed that he has forfeited any claim to representing all Israelis."

Slate's Joshua Keating likens the outcome, external to the 2013 Israeli election and Mr Netanyahu's split with former rival that set up this election - "In other words, while Israeli voters may have chosen continuity, there's a good chance they'll be voting again pretty soon."

Danielle Pletka of the American Enterprise Institute writes at CNN, external that Mr Netayahu's re-election will make it more likely President Obama make "even more concessions to ensure a deal between Tehran and Washington".

Confronting a tougher political battle battle than he anticipated, Mr Netanyahu made the election about security, primarily the threat posed by Iran.

Breaking political protocol, he bypassed the White House and gave a controversial yet compelling speech before the US Congress regarding the danger of a "bad deal" from the ongoing P5+1 negotiations with Iran.

Instead of an arrangement that would leave Iran with an active civilian nuclear capability and what he viewed as an unacceptably short leap to a weapon, Mr Netanyahu advocated for the status quo - keep sanctions on Iran until it started acting like a "normal country".

Reaching a nuclear agreement with Iran has arguably been Mr Obama's highest foreign policy priority.

Israeli voters expressed concerned about the country's high cost of living

The president does not see the current situation as sustainable, with indefinite isolation or confrontation making an Iranian nuclear weapon more likely, not less.

Mr Netanyahu's election does not materially impact the prospects of an agreement.

They are complicated enough in their own right as Washington and its negotiating partners attempt to thread an incredibly tight needle while overcoming decades of mistrust on all sides.

Given that Mr Obama was already confronting bipartisan scepticism and is constructing a prospective agreement that Congress can criticise but not stop - even with the documented opposition of 47 senators - Mr Netanyahu will ultimately have to live with whatever Mr Obama does.

From an American standpoint, Mr Netanyahu should have stopped there. He didn't.

Over the weekend, he made explicit what many, particularly the Palestinians, had long believed.

The negotiations between the West and Iran are unlikely to be changed by Mr Netanyahu

As long as he is prime minister, there will not be a Palestinian state. He even acknowledged that his administration used settlement construction to undermine the process.

These statements sent a moribund peace process into freefall, calling into question the future of the Oslo process.

But in his political desperation, Mr Netanyahu gave some unexpected (and from an American standpoint profoundly unhelpful) ammunition to Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas.

The Palestinians have long argued that, notwithstanding Mr Netanyahu's 2009 speech at Bar Ilan University grudgingly accepting the two-state solution, that he had no intention of ever reaching an agreement with the Palestinians.

Assuming Mr Netanyahu forms a government, that becomes Israel's de facto policy.

The European Union has called for a resumption of the peace process, but there is no longer a credible foundation for such a step.

Palestinians will likely use Mr Netanyahu's comments to push against Israel in the United Nations

This leaves the Palestinians free to challenge Israel through various United Nations organisations.

Attempts to de-legitimise Israel through the UN scores political points but doesn't move the Palestinians closer to an actual state.

This further isolates Israel internationally, but it is at present a price it consciously decided to pay.

The deadlock leaves Mr Obama with a chronic pain that, as with his recent predecessors, he will bequeath to the next occupant of the White House.

PJ Crowley is a former US Assistant Secretary of State and now a professor of practice and fellow at The George Washington University Institute for Public Diplomacy & Global Communication.

- Published18 March 2015

- Published18 March 2015