The Texas 'liberty cities' rebellion

- Published

Kingsbury residents hold the proposed boundaries of their incorporated town

Texas is known for its low taxes and limited government - but its big cities look a lot like big cities anywhere, with their own rules and regulations. As they spread across the neighbouring countryside, some unhappy rural residents are drawing a line in the sand.

There's not a whole lot to Kingsbury, Texas. In fact, it's not even really a town.

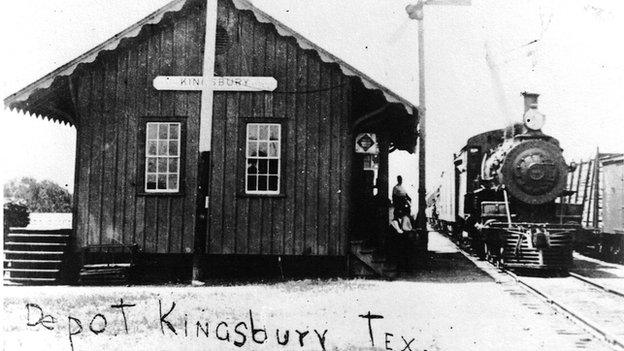

Technically Kingsbury is just part of Guadalupe County, in the central part of the state. It is a name and a postal code on a row of dilapidated buildings dating to the early 1900s, when the area had a bustling railroad depot, lumberyard and supporting businesses.

As with many old Texas settlements, however, the trains - the lifeblood of commerce - eventually stopped visiting. The lumberyard shuttered, the hotels closed and the bank burned down after the manager ran off with all the money.

Now all that remains of Kingsbury are a few shops, a volunteer fire department, a local cafe and houses dotting large pastures replete with grazing cattle. Lots of cattle.

That's just the way many Kingsbury residents like it, of course. They - or their forebears - did not come to the area to be part of the hectic city life.

"We wanted to be out in the country," says George Hext, a retiree who calls Kingsbury home. "It's nice and quiet."

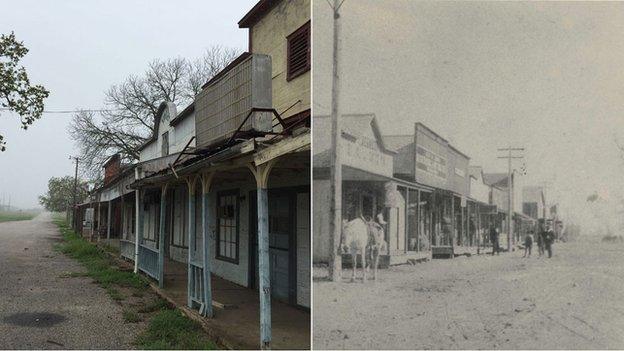

"The bank was the nicest building in town," says Bob Grafe, a Kingsbury resident

But while folks like Hext may not be keen on Texas cities, metropolitan Texas could be heading their way.

It is a fate familiar to a growing number of rural residents in this booming state.

Although it is known more for big skies than big skylines, Texas is swelling with people. The state as a whole saw its population surge, external by 451,321 - the most in the nation - from July 2013 to July 2014. Five of the 10 fastest-growing cities in the US in 2014, according to, external Forbes magazine, are located in the state.

Even the modestly sized town of Seguin, Kingsbury's closest neighbour, grew, external by more than 14% from 2000 to 2010.

Its population is now 27,000 - not big by any measure, but it's likely to keep booming, thanks to the arrival of a massive engine-manufacturing plant in 2014 and a global food-processing facility slated to open in 2016.

Shirley Nolen's mother (top right) grew up in Kingsbury

Shirley Nolen, a fifth-generation resident of Kingsbury, eyes Seguin warily. She says the town is laying claim to potentially lucrative real estate near Kingsbury, setting the stage for the kind of municipal regulation - and, eventually, taxation - that country dwellers like her had sought to avoid.

"We basically report to Seguin," says Bob Grafe, a Kingsbury resident. "It's regulation without representation."

Seguin's "city limit" signs are creeping ever closer to Kingsbury

And so Nolen, Grafe and a handful of residents in and around Kingsbury have come up with a plan. They want to incorporate what they can of Kingsbury and make it a low-tax, low-regulation symbol for other small towns battling big-city encroachment across the state.

"We want our downtown," Nolen says. "We want our churches. We want our post office. We want our community back, and we're not stopping."

The movement behind the town

Kingsbury's would-be founders are making their little piece of the Texas countryside the latest battleground in what's been called the "liberty city" movement.

It is a cause championed by Jess Fields, a policy analyst for the conservative Austin-based think tank the Texas Public Policy Foundation.

"The liberty city idea kind of goes back to the basic concept that people have a fundamental right to determine what kind of government they want to live under," Fields says.

He says the big Texas cities have veered far outside of the essential purpose of government, with lifestyle regulations that infringe on personal liberties - such as limits on the use of firearms, plastic bag fees, excessive building codes and punitive taxes.

"I don't deny that some of these regulations are well intended to promote public health and safety, but there's a point at which these good intentions are eclipsed by their clear, negative, unintended consequences," he says. "We don't want the government to tell you how to do every little thing with your property and what to do with your life."

Downtown Kingsbury, then and now

Earlier this year state Senator Konni Burton introduced "liberty city" legislation, SB710, external, which would lower the hurdles to incorporation for small towns - if they agree to a "bill of rights" that includes the right to bear arms, religious practice and free speech, and protection from unreasonable searches, "including the collection of data, surveillance and forceful search methods". It also requires that any change in property taxes are approved by at least 60% in a public vote.

According to Art Martinez de Vara, Burton's chief of staff, the guarantees would ease concerns of wary rural residents who think that, despite assurances to the contrary, newly minted local governments will eventually become as power hungry as their more established counterparts.

He says the legislation has been well-received, although it may take time for enough politicians to get on board.

"It's a really good experiment in democracy," he adds.

Liberty City on a hill

De Vara is a particularly well-qualified advocate for liberty cities, as he is also the mayor of Von Ormy, a small town near San Antonio that is held up as the shining example of what a liberty city can be.

When Von Ormy was founded in 2008, it had a minimal real estate property tax. That tax has now been completely abolished, and the limited city government is funded from business fees and a sales tax.

Every city service that can be outsourced - such as trash collection - has been. The fire station is mostly volunteers. The police force? Mostly volunteer as well, serving as a supplement to the county sheriff department.

"Other cities have a police department, and they don't want the sheriff in their town," he says. "They have high taxes. We try to do it differently."

Mayor Art Martinez de Vara runs the "liberty city" of Von Ormy

He notes that the city has no gun restrictions and no smoking prohibitions, and is the only town in the county without a fireworks ban.

"You can buy cigarettes, carry them in a plastic bag, then smoke them in our town," he says. "We don't promote it. We don't not promote it. It's the free market."

He adds that they do have building safety codes, although inspection fees are minimal.

"We're not anarchists," he says. "We just believe in limited government."

Most big Texas cities have gone deep into debt to fund major infrastructure projects, as well as benefits - such as pension plans and healthcare - for city workers, he says. The only way to balance the books without raising taxes - and putting themselves at a disadvantage compared to other cities - is to expand.

It is a short-term solution, he says, but it is unsustainable. More than that, cities are grabbing only the most economically viable of the outlying areas, leaving the rest with a minimal income base and little or no services.

"They're cherry-picking," he says, pointing to the example of Kingsbury.

"Is Seguin going to annex Kingsbury proper anytime soon? Probably not. But they're certainly going to pick around it, to the point where if Kingsbury were to wait 10, 15, 20 years to incorporate, there wouldn't be anything of value that they could make into a sustainable city. It's basically forcing them into generational underservicing."

For the residents of Kingsbury, however, it comes down to a simple goal. "We're here to keep Kingsbury alive," Nolen says.

A vote among the 166 registered voters will be held on 9 May, and a simple majority is enough to put Kingsbury, officially, on the map.

"This is home," Nolen says. "It may not be a lot to look at for other people, but to us it's home."