Sailor rescued: How do you survive 66 days lost at sea?

- Published

Louis Jordan on his boat Angel, before his ill-fated trip

A US sailor who was missing at sea for more than two months has been found alive and well, sitting on his upturned boat. How is it possible to survive so long adrift?

Louis Jordan, 37, set off from the marina at Conway, South Carolina, on 23 January, telling his family he was going on a fishing trip to "catch some big ones".

What happened next is unclear. At some point, the sailor told media, his boat "flipped" in the night during bad weather. The mast snapped in half and the boat began filling with water.

His family reported him missing, but the Coast Guard were unable to find him. Even his father, Frank, lost hope of ever seeing his son again.

But 66 days later, a passing German ship found him clinging to his capsized vessel, 200 miles (320km) off the coast of North Carolina.

Footage of the rescue was released by the US coast guard

Mr Jordan said he felt like he had been adrift for "100 days", but surprisingly he showed little sign of dehydration, sunburn or malnutrition, and appeared in rude health for a man who had apparently been surviving on raw fish and rainwater.

While not directly disputing Mr Jordan's story, the Coast Guard say the full story of what happened is still far from clear.

"We don't have any reason to believe anything he told the media is false," said spokesman Nate Littlejohn. "However, we don't know for a fact he was out at sea for 66 days. All we know is his family reported him missing on 29 January. We've not heard the whole story yet."

Louis Jordan's ordeal

23 January: Sails out of the marina in Conway, South Carolina, on his boat Angel

29 January: Reported missing by his father Frank, who told Miami Coast Guard his son had not been seen or heard from in a week

8 February: Search operation launched by Coast Guard

18 February: Search abandoned with no sign of Mr Jordan or his vessel

2 April: Found sitting on the hull of his capsized boat, 200 miles east of Cape Hatteras, off North Carolina.

Mr Jordan's two months at sea is a mere fraction of the 13 months that Mexican Jose Salvador Alvarenga spent cast adrift in the Pacific Ocean.

The bedraggled fisherman eventually washed up 6,000 miles away in the Marshall Islands after 440 days alone, telling reporters he had stayed alive by eating fish and drinking the blood of sea turtles.

"His story sparked a lot of debate - was this doable or not doable?" said physiologist Professor Mike Tipton of Portsmouth University, co-author of the book Essentials of Sea Survival.

"And when you think about it - he was drifting in an area of the Pacific with sufficient rain, where cold temperatures are not a threat, and he had plenty of experience catching fish. He had the combination of being the right kind of person and a lot of luck."

Louis Jordan looked well as he walked into hospital after his rescue

The hierarchy for survival, he says, is oxygen, circulation, body temperature, water and then, finally, food.

To drink, Mr Jordan says he collected rain water and rationed what he drank to about a pint (568ml) a day, which according to Prof Tipton is just above the daily minimum needed to stay alive (300ml-500ml).

"You need that to maintain the function of the kidneys and other vital organs. Without it you won't last more than a couple of days."

Another good source of hydration is the blood of turtles and seabirds - a 20kg (44lb) turtle can provide about a litre of blood.

The accounts of castaways who survived by drinking their own urine make no sense, Prof Tipton says, because urine hastens dehydration.

As for food, if you start with lots of body fat you can survive for a long time, Prof Tipton says.

Mr Jordan told reporters he ate pancakes and raw fish which he caught "with his laundry" after having no luck with his fishing rod.

But eating fish has a serious downside for extreme survival. "They're full of protein. And protein requires a lot of extra water to flush out the by-products of its digestion," Prof Tipton explains.

"You're better off with fats and sugars - and that's exactly what survival rations are made of. But of course you're unlikely to catch a bar of chocolate floating by."

The ideal meal for a drifting sailor is not fish but turtles - which have a lot of fat under their shells.

Famous castaways: Who survived longest at sea?

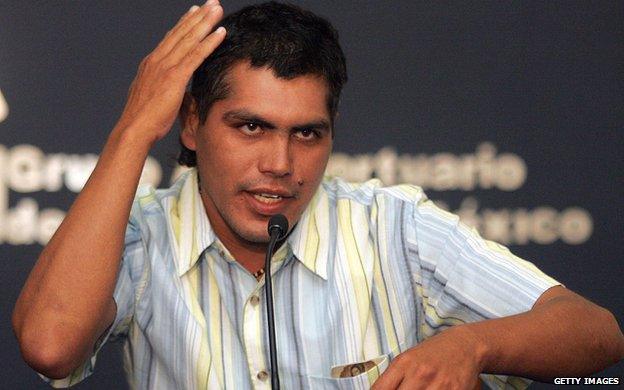

Mexican shark fisherman Jesus Vidana describing his crew's remarkable story of spending 270 days adrift

Mexican Jose Salvador Alvarenga endured 440 days drifting across the Pacific Ocean until he was found in the Marshall Islands, emaciated and wearing only his underpants, having swum ashore.

Poon Lim, a Chinese sailor during World War II, set a record for the longest survival on a life raft. He survived 133 days alone in the Atlantic

In 2006 Mexican shark fisherman Jesus Vidana and his crew spent 270 days adrift in the Pacific Ocean before a Taiwanese tuna fishing vessel rescued them off the Marshall Islands.

US adventurer Steven Callahan survived 76 days in a life raft in the Atlantic in 1982 after a whale rammed into the hull of his sloop, Napoleon Solo.

The fact that Louis Jordan was found sitting up out of the water is also highly significant - it could very well have saved him from hypothermia, says Prof Tipton.

"Your body cools six times faster in water. So you're better off out than in," he explains.

Even so - the unusually cold winter in North Carolina would have put the sailor in serious peril, depending how far from the coast he was drifting.

"If you plot the great sea survival stories on a map, they all tend to be in Equatorial waters," says Prof Tipton.

The hot, tropical sunshine may increase your danger of dehydration and sunstroke, "but you can avoid that if you create shade and collect enough rainwater", he says.

Hypothermia, he says, is much harder to battle. If Louis Jordan really has spent the last 66 days capsized drifting up and down the chilly Carolina coastline, he must have had excellent clothing or shelter to protect from the elements.

Jim Hench, professor of oceanography at Duke University, says that where Mr Jordan was found - 200km (124 miles) east of Cape Hatteras - meant the vessel would have benefitted from the warm currents of the Gulf Stream.

"Remember those waters come up from the Caribbean. At this time of year they could have been as warm as 20C-25C," he says.

However, Mr Jordan could not have been exclusively drifting in the Gulf Stream for 66 days, because if he had "he would have gone a lot further".

"The Gulf Stream flows at about the pace of a slow walk - which is actually very fast by ocean standards. You could move a long way in 66 days - perhaps even the width of the Atlantic Ocean," he calculates.

"When I saw where he was picked up, I was very surprised to hear he'd been drifting for two months."

It seems more likely that Mr Jordan spent that time drifting closer to shore, Prof Hench says.

Mr Jordan says that when first he saw the German container ship, he did not believe it was real.

But nevertheless, he knew what to do: "I waved my hands real slowly, and that's the signal: 'I'm in distress help me,'" he said.

He credited his faith with keeping him mentally strong throughout his lonely struggle, telling reporters that he read his Bible and prayed regularly.

He said he wasn't as concerned about his own wellbeing as he was for his family and friends who would think he was dead.

Prof Tipton says this psychology is typical of survivors. "Studies show there are attitudes people get themselves into in these extreme situations.

"They don't give up or feel hopeless - they focus on short term goals, surviving to the evening and setting themselves tasks. The explorer Shackleton was very good at that.

"The other thing people do is focus on their family. Those positive mental images are very important for survival.

"And I noticed - when he was finally rescued - Mr Jordan had a very emotional phone call with his father."

- Published3 April 2015

- Published3 April 2015