Baltimore's dual identity explains unrest

- Published

Baltimore fire-fighters battle a blaze in west Baltimore on Monday

Why Baltimore?

That's the question being asked after the city erupted into riots and looting on Monday. Since Michael Brown was shot dead by a police officer last year in Ferguson, Missouri, dozens of incidents questioning the use of force by police have emerged in cities and towns across the US.

But only Baltimore has seen unrest like Ferguson.

Baltimore is a thriving major city with black leadership. The thinking goes: This shouldn't be happening here.

To understand why you have to understand that Baltimore is actually two cities: One is a city mired in decline and poverty, made famous by the TV show The Wire. Another is a city on the rise with a shiny waterfront and increasing numbers of young affluent residents.

To keep the affluent Baltimore viable, city officials have pursued a laser-like focus on crime, ensuring its new up-and-coming neighbourhoods stay safe. Meanwhile, in sprawling low-income areas on the city's east and west sides, the police have been omnipresent. Sometimes their methods have bordered on draconian.

The success of the new Baltimore has never touched many parts of the city, most prominently the west side where this week's violence began. Take away the towering downtown, the waterfront and other affluent enclaves and Baltimore suddenly looks a lot like Ferguson - poor, harassed and angry.

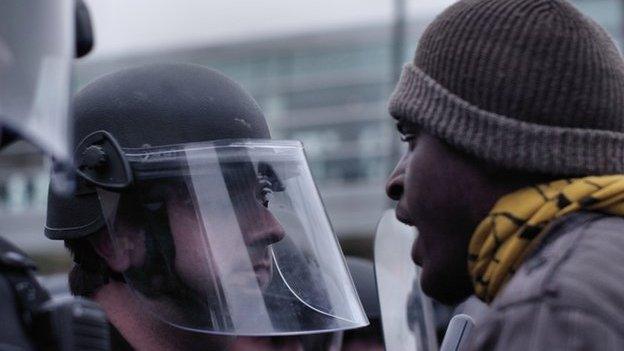

Police said many of the rioters were teenagers who had just been released from school

In the 1980s and 1990s, Baltimore was haemorrhaging residents because of its high-crime rate, partly brought on by the city's massive heroin trade. David Simon, the creator of The Wire, worked then as a police reporter for The Baltimore Sun, making him an expert on the city's high-crime areas. Those experiences would later inform The Wire.

In the late 1990s, Martin O'Malley, the city's first white mayor after years of black leadership, adopted a get tough approach on crime. Mr O'Malley invested heavily in city police to turn around the fortunes of the once thriving city. He launched CitiStat, a statistics-based approach to crime fighting, sending police resources to exactly where the crime was.

His successors, Sheila Dixon and Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, both black women, maintained strong support for the police department.

For a time, the get-tough approach worked: the number of murders finally plunged below 200 in 2011. It had been over 300 several times during the 1980s and 1990s.

When budget cuts were required, police were spared while other parts of the city like the parks and recreation department felt the axe. While other cities stressed community outreach and gentler methods, Baltimore stayed the course with tough policing techniques.

But in recent years, crime has been inching back despite more and more effort from the police department. The Baltimore Sun, external published a special report last year showing the city paid nearly $6m (£3.95m) in recent years to victims of police beatings. The Justice Department has launched an investigation into those claims.

The civic pride that courses through Baltimore's new affluent areas is absent in west Baltimore. What remains is suspicion, unemployment, poverty and frustration.

Late on Monday, on social media, young residents of the new Baltimore posted messages like "this is not the city I fell in love with".

And in a way they were right.

Tim Swift , externalworked as an editor at The Baltimore Sun from 2001 to 2014. He is now a news editor for The BBC in Washington.

- Published28 April 2015

- Published26 April 2015

- Published23 May 2016