Why do US police keep killing unarmed black men?

- Published

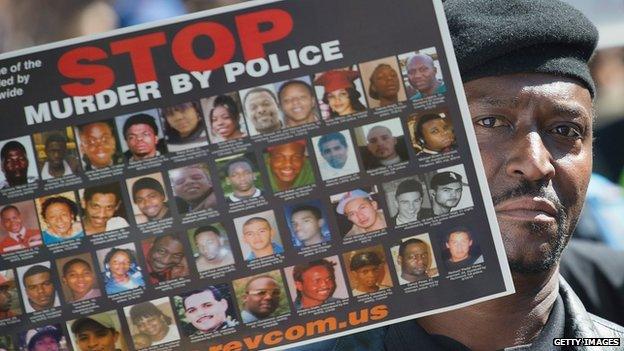

There have been large-scale protests against police brutality across the US

Recent high-profile cases of unarmed black men dying at the hands of the US police have sparked protests and civil unrest in several American cities.

The deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Walter Scott, and Freddie Gray are - some claim - evidence of long-standing problems with police racism and excessive violence.

Four expert witnesses talk to the BBC World Service Inquiry programme, including the head of President Obama's taskforce on police reform, Charles Ramsey.

Sam Sinyangwe: These are not isolated incidents

Sam Sinyangwe is a researcher and activist who started the Mapping Police Violence, external project.

Sam Sinyangwe was frustrated by the lack of official statistics on people killed by police officers

"I'm 24 years old. I'm a black man. It's incredibly depressing to see people just like me who have been killed.

"I started the project to provide answers in the wake of the shooting of Mike Brown. It's very heavy to read these stories, and yet it feels like the right work to do. It's important.

"There are statistics on all kinds of violent crimes. And yet, when it comes to people being killed by police officers, there's no data on that. So a light bulb went off in my head. I looked at two crowd-sourcing databases which collected all of the names. I then went through the media reports listing each of those people who were killed."

He counted 1,149 people of all ethnic groups killed by the police in 2014.

"I identified whether they were armed or unarmed. I identified them by race by looking at if there was an obituary or another picture of them online.

"In the aftermath of Ferguson [where the unarmed teenager Michael Brown was killed], there was this big question 'Is this a pattern, is this an isolated incident?' What [my data] shows is that Ferguson is everywhere. All over the country you're seeing black people being killed by police."

The youngest recorded was 12, the oldest 65. More than 100 were unarmed.

"Black people are three times more likely to be killed by police in the United States than white people. More unarmed black people were killed by police than unarmed white people last year. And that's taking into account the fact that black people are only 14% of the population here.

"It goes back to this question of how do they perceive young black men? There's something in the US called Vision Zero, a commitment by mayors to achieve zero traffic fatalities in a specified timeframe.

"We haven't seen mayors step up and make clear commitments to eliminate the level of police violence in their communities. I think that says a lot about the relative value that they place on those constituents' lives."

Lorie Fridell: Some police guilty of 'black crime implicit bias'

Lorie Fridell is an Associate Professor of criminology at the University of South Florida and was director of research at the Police Executive Research Forum.

Lorie Fridell cites research showing black people are often assumed to pose a higher threat

"I'm a white, middle-class professional woman. I enjoy a great deal of privilege. And I certainly have the black crime implicit bias: I am more likely to see threat in African Americans than I would Caucasians.

"Racial profiling was the number one issue facing police [in the 1990s], and I came to understand two things. Bias in policing was not just a few officers in a few departments; and, overwhelmingly, the police in this country are well-intentioned. I couldn't put those two thoughts together in my head until I was introduced to the science of implicit bias.

"We all have implicit biases whereby we link groups to stereotypes, possibly producing discriminatory behaviour - even in individuals who are totally against prejudice.

"The original 'Shoot, Don't Shoot' studies, external have a subject sitting in front a computer monitor and photos pop up very quickly, showing either a white or black man. That man either has a gun in his hand or a neutral object like a cell phone. The subject is told 'if you see a threat, hit the 'shoot' key and if you don't see a threat, hit the 'don't shoot' key'. "

The studies suggest that implicit biases affect these actions - for example in some studies people are quicker to 'shoot' an unarmed black man than an unarmed white man. A Department of Justice report released in March looking at the use of deadly force by Philadelphia police, external, supports the idea that police are susceptible to implicit bias:

"One of the things they looked at is what they called threat perception failure. The officer believed that the person was armed and it turned out not to be the case. And these failures were more likely to occur when the subject was black [even if the officers were themselves black or Latino].

"Officers, like the rest of us, have an implicit bias linking blacks to crime. So the black crime implicit bias might be implicated in some of the use of deadly force against African-Americans in our country.

"An important message in our training is that stereotypes are based in part on fact, and we have to recognise this because in our country, people of colour are disproportionately represented amongst the people who commit street crime.

"That does not give you licence to treat every individual in a group as if they fit the stereotype, that's where we go wrong."

Seth Stoughton: 'Warrior police' culture endangers civilians

Former policeman Seth Stoughton is now a law professor at the University of South Carolina.

Seth Stoughton argues police training should focus more on conflict resolution than the use of force

"The first rule of law enforcement is to go home at the end of your shift. The key principle is officer survival. That's what all training is designed to promote. But it ends up endangering civilians rather than preserving their safety.

"The warrior culture - the belief that police officers are soldiers engaged in battle with the criminal element - that has contributed to some shootings that were most likely avoidable.

"It starts in police recruitment videos that show officers shooting rifles, strapping on hard body armour, using force. That attracts a particular type of candidate, and the Police Academy further entrenches this.

"It teaches officers to be afraid by telling them that policing is an incredibly dangerous profession.

"Officers are trained to view every encounter as a potential deadly force incident: you walk up to a person who is loitering outside of a convenience store, their hands are in their pockets. You as the officer begin talking to them, and without saying a word they pull a gun out of their pocket and begin shooting you.

"Training involves an average of about 60 hours on deadly force - the use of firearms - and just over 60 hours on self-defence. Compare that to de-escalation conflict resolution training: the average there is only eight hours of training, and most of that is classroom-based.

"When the military is designing a mission, they have in mind the fact that they're going to lose soldiers. The police profession has strongly repudiated that notion. No officer fatalities are acceptable.

"If all of the states had the same approach and the same numbers of officer-involved homicides as the best states, the states that had the fewest, we could expect about 300 to 600 lives to be saved every year."

Charles Ramsey: We have to fix wider social problems first

Charles Ramsey is the Commissioner of the Philadelphia Police Department, and was asked by President Obama to run the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing, external.

Commissioner Ramsey argues that police officers are also the victims of violence

"We live in a society where everybody wants to point fingers, but we have a lot of deeply-rooted societal problems: poverty, education, poor housing stock.

"We've got to deal with the issue of extreme poverty. Philadelphia has the highest rate of poverty among US cities. You have an underground economy that supports many of these neighbourhoods - drugs, prostitution, illegal cigarette sales.

"Why are police in large numbers in some of these neighbourhoods? We have to deal with the reality that there's a disproportionate amount of crime occurring in many of these neighbourhoods.

"We've had several police officers shot and killed during the past seven years. I've had eight officers killed in the line of duty - five shot dead. So there is violence that takes place against police as well, and that needs to be taken into consideration."

To tackle the problem, he has divided Philadelphia into separate areas with their own teams:

"They have monthly community meetings to talk about crime and disorder. Cadets that come out of the academy are assigned to foot patrol right away, they don't automatically go into cars. So that they actually get to know people in these challenged communities, good folks that are there entrapped in certain conditions."

In response to the Department of Justice report criticising Philadelphia police's use of force, Commissioner Ramsey introduced new training that focuses on de-escalation, as well as armed response:

"Putting them in scenarios where they have to exercise good judgement and being able to critique that so that when they are in these real live situations, their reaction, their response, is really more consistent with what the actual threat is."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 1205 GMT/1305 BST. Listen online or download the podcast.

The link in this story to the "Shoot, Don't shoot" studies referred to by Professor Lorie Fridell has been updated to reflect more accurately the research.