John Nash's ground-breaking contributions to maths

- Published

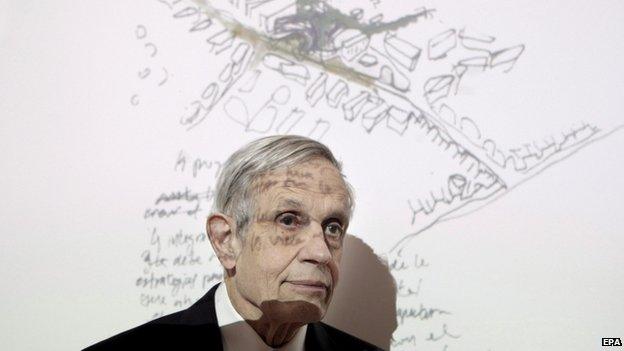

Nash made his name in game theory but made other contributions to maths too

Genuinely new, genuinely brilliant ideas in mathematics are hard to come by.

Undergraduate maths, for example, contains few topics imagined after 1950.

That John Nash made ground-breaking contributions in mathematical areas as diverse as games, geometry and topology, and partial differential equations therefore establishes his place in history.

Much more striking, though, is the continuing resonance of his ideas.

Just last week, as Nash was in Oslo collecting the prestigious Abel Prize, colleagues of mine began applying his famous concept of equilibrium to help address one of society's much more contemporary problems - that of supplying electricity cheaply, reliably and cleanly.

Great new mathematical ideas have a balance to strike - they must be precise enough to allow detailed conclusions to be drawn, and yet sufficiently loose that they can be useful in a wide range of problems.

His advances in game theory have influenced everything from computing to biology

Nash equilibrium is just such an idea, and was a fundamental contribution to the nascent mathematical theory of non-cooperative games - situations where one player's fortunes depend on the actions of others, and everybody tries to do as well for themselves as possible.

Nash's definition of equilibrium was definitely loose enough: "A configuration of strategies, such that no player acting on his own can change his strategy to achieve a better outcome for himself."

Indeed it had so much slack that John von Neumann, the originator of game theory, reportedly told Nash in person that his work on the concept was "trivial".

Crucially, though, the Nash equilibrium offered something truly new - the ability to analyse situations of conflict and co-operation and produce predictions about how people will behave.

In addition to its obvious range of applications in politics and economics, the depth of the idea is illustrated by the traction it gained at the Rand corporation, the top secret US Cold War think tank.

While Rand had already identified game theory as a promising secret weapon against the Soviet Union, before Nash their analysis was "zero sum".

In other words their existing version of the theory was one of pure conflict in which the two sides shared no common interests.

There was a growing appreciation at Rand that this assumption was not realistic.

Since Nash's equilibrium concept is wide enough to allow the analysis of non-zero sum situations in which some goals are shared, he was immediately hired by Rand on completing his PhD in 1950.

Nash's other mathematical contributions should not be underestimated.

Indeed he always considered himself to be a pure mathematician, in contrast with the applied nature of game theory.

John von Neumann, who invented game theory, once called Nash's work "trivial"

In the 1950s, Einstein's theories on the relationships between time and space led to a growing interest among mathematicians in high dimensional geometry.

In this context Nash's Embedding Theorem resolved a long-standing open problem among pure mathematicians, and the manner in which he proved it caused no little incredulity and controversy among his contemporaries.

His major contribution to the theory of differential equations may have led to the award of the prestigious Fields Medal, had his contemporary Ennio de Giorgi of Pisa not proved the same result just months earlier by different methods.

Nash's famous equilibrium, though, has grown to be perhaps the most important idea in economic analysis and has found application in fields as diverse as computing, evolutionary biology and artificial intelligence. More recently it has been used in studies of corruption and also name-checked amidst the Greek financial crisis.

It has of course been criticised, questioned and varied. Perhaps fittingly for an equilibrium, though, it is the balance between precision and generality which has made this beautiful and natural concept endure.

- Published24 May 2015

- Published24 May 2015

- Published18 February 2015