Boston bombing: The day when the victims confronted the bomber

- Published

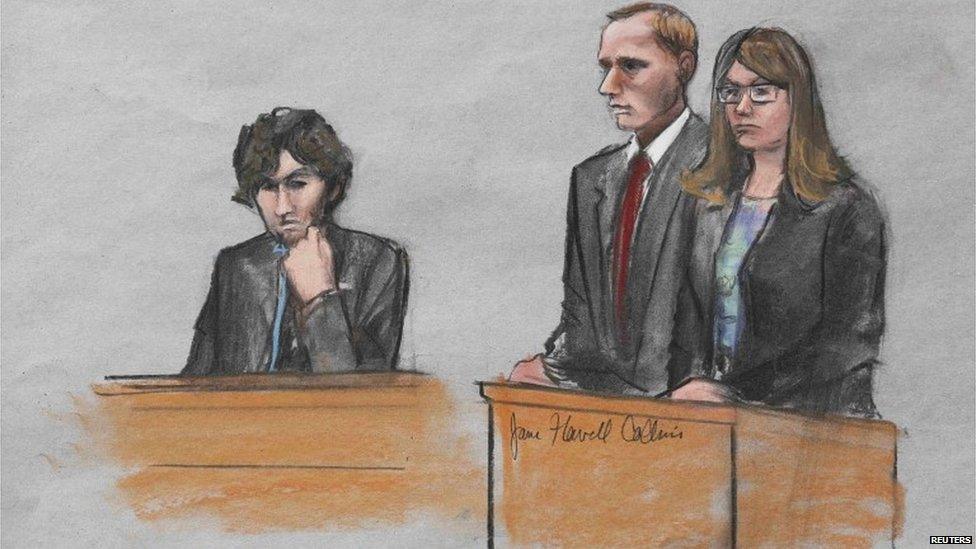

Bill and Denise Richards give evidence as Tsarnaev listens

The crime had seemed impersonal and chilling - the bombing of a crowd of spectators. Yet it led to a strangely personal day, with the bomber and his victims speaking up for the first time.

It was an "extraordinary case", Judge George O'Toole Jr said in Courtroom Nine in the John Joseph Moakley Federal Courthouse in Boston.

It was also revealing - in a profound sense.

People shared details about their lives in a way they would never do under ordinary circumstances.

Through so-called victims' impact statements, more than 20 men and women talked about their experiences after the bombings, describing wounds, loves, break-ups, dreams and what they thought of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev

They'd got to know him well.

They'd personally experienced what he and his brother, Tamerlan, had done.

They also knew the stories of the dead.

Martin Richard, eight, a student at Neighborhood House Charter School, was killed in the explosions.

So were Krystle Campbell, 29, a restaurant manager, and Lingzi Lu, 23, a graduate student at Boston University. In addition, the bombs maimed 16 people and injured 260 others.

Mr Tsarnaev and his brother, Tamerlan Tsarnaev, later shot and killed Sean Collier, 27, a police officer.

The victims

Restaurant manager Krystle Campbell, 29, had gone to watch a friend complete the race

Chinese graduate student Lu Lingzi was studying statistics at Boston University

Eight-year-old Martin Richard was standing with his family, cheering the runners

Police officer Sean Collier was shot by the Tsarnaev brothers as they tried to evade arrest

Besides knowing about his crimes, they'd heard about his life during the trial. They had also been watching him for weeks.

In their prepared statements - some were still editing their remarks as they sat in the courtroom - they recalled jokes he made with his lawyers in the courtroom and how he looked ("smirking", said one person).

They also spoke to him about the sentence that had been imposed - death.

"My hope and desire," said Jennifer Kauffman, who ran a coaching business and suffered neck and back injuries in the bombings, was he would be "willing to forgo your right to appeal so we can all move forward in peace".

Another woman, Karen McWatters, had lost her friend, Krystle Campbell, in the attacks. She looked at him. "Why didn't any of us who sat in the courtroom for that long trial see any remorse?" she said.

"Your friends have abandoned you," she told him, "and you will die alone in prison."

Marathon survivors Karen McWatters (left) and Heather Abbott leave court

And then he spoke.

People stared at him as he got to his feet. Then they listened.

"I am sorry for the lives that are taken," he said.

The idea of victims may have been an abstraction when he was planning the attacks. But now he knew their names - as well as "their faces", he said.

His voice was quiet. He stood up straight - and shifted his weight from one foot to the other.

He talked about "all those at that podium" - and waved his hand towards a section of the room where victims had spoken, including some who'd told him they wanted him to die.

"I pray for them and for their healing," he said.

Victims had spoken before in court, but only about what happened, not how they felt

After he sat down, everyone, the jurors, the people who had read statements, journalists, leaned back in their own seats.

The room was silent.

One woman, Erika Brannock, who lost part of her left leg in the explosions, shut her eyes for a moment.

Another woman pulled out a tissue.

Johanna Hantel, 55, who said she'd promised herself she'd keep running the marathon even though she'd received shrapnel wounds, looked over to people beside her as if to say - what should we do now?

Survivors said the Tsarnaev apology was not genuine

Not everyone was uncertain about how they felt, though.

"Sure, I heard him," said one man after the courtroom emptied out. He was wearing a baseball cap - and was holding a bouquet of flowers for a friend who'd also watched the trial.

"I don't care what he says," he said. "It's dead man walking as far as I'm concerned."

Another man who had got to know Tsarnaev had equally strong views - though his conclusions were different.

In his prepared statement, Bill Richard spoke clearly. His voice carried across the room as he spoke about his son, Martin.

In a photo taken before his death, Martin holds a poster board: "No more hurting people - peace." Today it became clear where he got that worldview.

In the courtroom his father wore a navy blue suit and neatly pressed trousers. He stood at the podium and talked about Tsarnaev.

"He could have changed his mind," he said. "He chose to do nothing.

"He chose hate. We choose love, we choose kindness. This is our response to hate. That is what makes us different from him."

Follow Tara McKelvey @Tara_Mckelvey, external on Twitter.