All you need to know about Uber

- Published

Uber says it "seamlessly connects riders to drivers"

The taxi-hailing app Uber has expanded rapidly since its launch and gained popularity with users as fares are generally cheaper than with traditional taxis.

However, it has faced fierce and sometimes violent opposition in various parts of the world.

In some of the latest trouble in South Africa, Uber drivers have complained of intimidation and harassment by their rivals for business.

Here is what you need to know about the upstart transport firm.

Uber connects customers and drivers

Uber's growth has been met by protests

Founded just six years ago, the San Francisco-based Uber "seamlessly connects riders to drivers", as the company puts it.

Users download an app which uses GPS technology to locate available drivers.

You tap the screen to hail a cab and pay automatically on arrival with a credit card. Fares are usually lower than with traditional firms.

It operates in 57 countries, but Uber's ambitions go beyond providing taxis - it has also trialled courier and fast food delivery services.

It makes big money

The firm is just six years old, but its expansion has been swift

Uber takes a cut of each fare. Since it does not directly employ drivers, or own the vehicles, costs are kept low.

Growth has been fast - some forecasts, external put revenues this year at around $2bn (£1.2bn).

It has also attracted huge amounts of funding. A recent valuation estimates the company as worth over $50bn (£31.7bn).

At this level, should Uber go public, it would be the biggest start-up flotation since Facebook.

You could be an Uber driver

The service needs a large pool of drivers to provide a reliable service, and is keen to stress how easy it is to join.

You will need your own car for starters, and to cover the costs of fuel and servicing.

The company also conducts background checks on potential recruits.

For drivers, despite the lower fares, there are obvious perks, such as being able to choose your own hours.

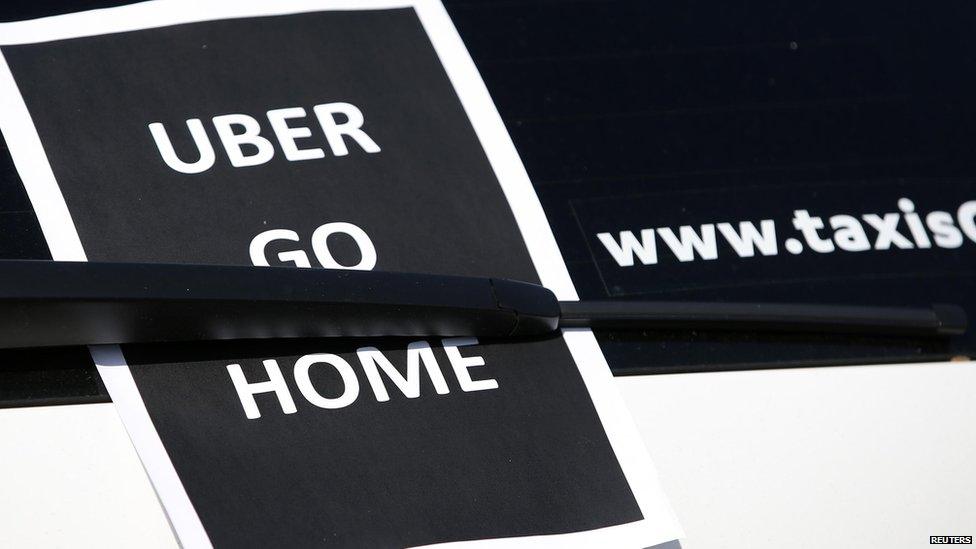

It has angered traditional taxi drivers

French taxi drivers overturned an Uber vehicle at a recent protest

Uber's growth has been matched by protests around the world. Canada, France, Hong Kong, India, South Africa, the US and UK have all seen demonstrations.

Such protests have brought gridlock to major capital cities. Occasionally, like in France, they turned violent.

The firm has had to provide security to protect its drivers in South Africa after threats from traditional drivers.

Broadly, taxi drivers accuse Uber of unfair competition, undercutting prices by allowing unlicensed drivers to escape regulation required for the professionals.

There have been other controversies too

Some of Uber's drivers have protested against working conditions

An Indian woman who says she was raped by an Uber driver in Delhi has filed a lawsuit against the firm, accusing it of failing to ensure her safety.

Uber said it was co-operating with the authorities. Its vetting process has also been put under the spotlight by allegations of sexual assaults by drivers in the US and Canada.

The company has been accused of aggressive business practices, including poaching drivers from rival Lyft.

And Uber executive Emil Michael said he was "plain wrong" for suggesting hiring researchers to dig up dirt on journalists who wrote negative reports on the company.

But it is most likely here to stay

Despite opposition, like this protest in London, Uber has proved popular

Uber's popularity makes it hard to see it disappearing soon. History has looked more kindly on disruptive technology than its critics, whether it be mechanised looms in the Industrial Revolution or audio downloads.

But the firm does face challenges. Local regulations could bite, raising fares - a court in California last month ruled in favour of an Uber driver who argued she was an employee, not a contractor, and so was owed expenses.

It has been banned in several countries. South Korea charged nearly 30 people linked to the company with running an illegal taxi firm.

Uber also faces competition from other cab-hailing services, such as China's Didi Kuaidi, which recently attracted $2bn (£1.2bn) in funding.

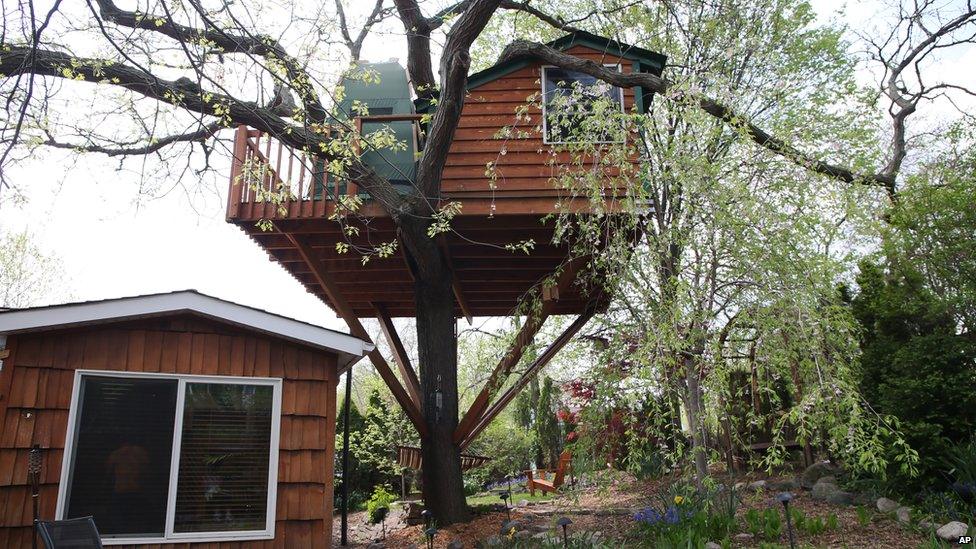

And the model is a winning one

Similar to Uber, Airbnb connects customers wanting accommodation to suppliers - like of this treehouse

Whatever Uber's future may be, it is part of a wider network of apps using similar business models.

At its core, Uber links customers to something they want - in this case a taxi - stripping away the need to make a phone call or even a Google search.

This can easily be adapted. Want somewhere to stay? Try Airbnb. How about a takeaway? Use Just Eat.

And it is this "interface" between consumer and supplier, as French media executive Tom Goodwin puts it, external, where "all the value and profit is".

- Published8 July 2015

- Published15 May 2015

- Published3 October 2014