Lengthy election could be recipe for Canadian chaos

- Published

- comments

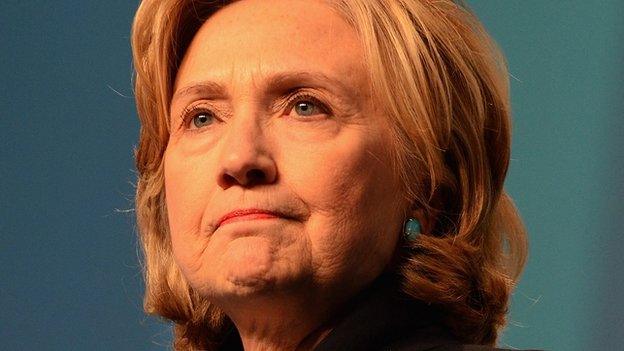

Stephen Harper says Canadians should "stay the course"

The Canadians are off and running in what will be the nation's longest general election campaign since 1874.

Over the weekend, Prime Minister Stephen Harper formally launched the nation's electoral season, which will last a whopping (by Canadian standards) 78 days, before voters in 338 electoral constituencies, called ridings, head to the polls on 19 October.

(That sound Canadians may hear is laughter from US presidential candidates, who take 78 days just to come up with a catchy name for the "independent" committee they'll use to rake in millions from rich donors.)

The decision to kick off the race so early - previous campaigns have lasted about five weeks - is seen as a tactical move by the Conservatives, who can bring the most financial resources to bear over a lengthier campaign season that has strict spending caps (cue more laughter from the Americans).

Mr Harper started his quest to become the first prime minister in more than 100 years to win a fourth consecutive term with that familiar trope for incumbents everywhere: "It is time to stay the course and stick to our plan".

But such rhetoric may not fly this time. Thanks to the bottom dropping out of the global energy market, Canada's oil-and-gas-dependent economy has hit the skids. The nation's gross domestic product has been shrinking all year, and its dollar - which usually trades at near parity with the US dollar - is currently worth only 78 cents.

Add several political scandals in the Conservative ranks, and the kind of concerns about stagnant wages and growing income inequality that are familiar to much of the Western world, and it's a recipe for electoral upheaval.

Justin Trudeau has the famous last name, but can he attract Canadian voters like his father?

It was just a few months ago that the Conservatives lost a provincial election in Alberta, a right-wing stronghold for more than four decades. As some wags, external put it, the resulting political shockwaves were akin to what would happen in the US if Republicans were to lose a major election in a solid conservative state like Texas.

There's also dissatisfaction in some quarters with Canada's robust - some would call it overly assertive - foreign policy under the Conservatives and concerns about balancing domestic security and civil liberties.

While the disillusionment with Mr Harper's party is real, however, Canadians seem legitimately uncertain about which opposition party to support. The Liberals have been the traditional left-leaning party in Canada, but their leader, Justin Trudeau - eldest son of Liberal legend Pierre Trudeau - is viewed by some as young and untested. Many disaffected progressives are turning to Thomas Mulcair and the New Democrats, which pulled off the upset in Alberta.

Both centre-left parties are polling, external alongside the Conservatives at around 30%. Throw in the Greens, the Strength in Democracy Party and the Bloc Quebecois - the francophone separatist party that once had Canadians fearing an impending national disunion - and the end result is a muddle that may stretch well past election day.

New Democrat leader Thomas Mulcair hopes his party's win in Alberta foreshadows general election success

Given Canada's first-past-the-post voting system, it's entirely possible that the Conservatives could hang on to the government without the support of a majority of the nation's voters. Or Canadian voters could fall in line between one of the opposition parties and push it over the top.

If all this seems like a bit of deja vu for fans of English-speaking parliamentary democracies, it should. The dynamics at play here are sneakily similar to those in the recently concluded UK general election. Remember when pundits saw the incumbent British Conservatives fighting to hold onto power and issued grim forecasts of a hung Parliament with multiple left-leaning parties led by politicians of questionable abilities attempting to cobble together a governing coalition?

It didn't work out that way, of course. The Conservatives cruised to majority rule, the Scottish National Party sundered Labour and the Liberal Democrats were left licking their prodigious wounds.

So maybe all this talk of a close race will be for naught. Or maybe, just maybe, it will be the most exciting thing to happen in Canada since Ted Cruz.

- Published3 March 2015

- Published6 November 2016