UN: Seventy years of changing the world

- Published

Nick Bryant explains what the UN General Assembly is - and why it matters

"The UN was not created to take mankind to heaven, but to save humanity from hell."

So often repeated are the words of the Swedish diplomat Dag Hammarskjold, the organisation's most beloved secretary general, they have come to serve as a mission statement of sorts.

Additionally, they function as a crude benchmark against which the work of the United Nations can be judged.

When the organisation was formed in 1945, in the aftermath of World War Two and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, "hell" would have been the outbreak of a third global conflict and nuclear Armageddon, neither of which has come to pass.

Ghastly failures

But in those post-War years, as the full horror of the Holocaust was uncovered, "hell" also meant genocide, a word which had only just been coined: the systematic massacre of thousands of people because of their ethnicity, religion, race or nationality.

Here, the UN has not always been able to halt the descent into the abyss.

To its member states' eternal shame, on some occasions it has been a bystander to genocide.

In any historical ledger, Rwanda and Srebrenica, external stand out as ghastly failures.

During the Rwanda genocide, UN peacekeepers deployed in the country concentrated on evacuating expatriates and government officials, failing to intervene as 800,000 Tutsis and sympathetic Hutus were slaughtered.

Thousands of Muslims were massacred in Srebrenica in 1995

In Srebrenica in July 1995, more than 8,000 Muslims, mainly men and boys, were massacred by Bosnian Serb forces, which barged past Dutch soldiers wearing the distinctive blue helmet of the UN peacekeepers as if they weren't there.

What made the massacre all the more horrifying was that the Muslims had sheltered in enclaves deemed "safe areas" under the protections of the UN.

In some conflicts, such as Yugoslavia, the UN was slow to respond.

In others, such as Vietnam and the Iraq war, it was sidelined.

Its efforts to broker peace talks during Syria's civil war, now in its fifth year, have always ended in failure.

Now, a third UN envoy, the Italian diplomat Staffan de Mistura, is trying, without success so far, to break the impasse.

Peace has also proved elusive in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, one of the UN's first major dilemmas following its formation in 1945 and a long-running bugbear.

Sometimes the UN has been part of the problem rather than the solution.

Blue-helmeted peacekeepers have been accused of a litany of sexual abuses, most recently in the Central African Republic.

In Haiti, peacekeepers from Nepal were the source, the evidence suggests,, external of a cholera outbreak that has killed more than 8,000 people - though the UN refuses to accept any legal liability.

Lack of democracy

While the UN sees itself as a force for democratisation, it is a ridiculously undemocratic organisation.

Dag Hammarskjold had lofty ambitions for the UN

Its locus of power is the Security Council, where the five permanent members - the US, Britain, France, China and Russia - still wield crippling vetoes.

The Security Council, like amber encasing an extinct insect, preserves the influence of the victors from World War Two, freezing a moment in a time.

Tellingly, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt coined the phrase the "United Nations," he was referring not to the countries of the world but rather the Allied powers.

Germany and Japan do not have permanent seats on the Security Council, nor do India or Brazil.

Though every country has a vote in the General Assembly, a less powerful body, almost 75% of the world's population is effectively disenfranchised in the Security Council.

There, preposterously, one veto-wielding power can thwart the will of the other 192 members.

All five veto powers have to agree, for instance, on the appointment of secretaries general, enabling weak, if well-intentioned, compromise candidates, like the present leader Ban Ki-moon, to reach the top.

Many positives

For all its shortcomings, however, the United Nations can look back on much of the past 70 years with pride.

It is credited with brokering more than 170 peace settlements, though it has proved better at preventing nation-to-nation conflicts rather than civil wars.

The Cold War never turned hot, although there were Cold War proxy conflicts in Korea, Vietnam, Nicaragua, Angola, Afghanistan and elsewhere.

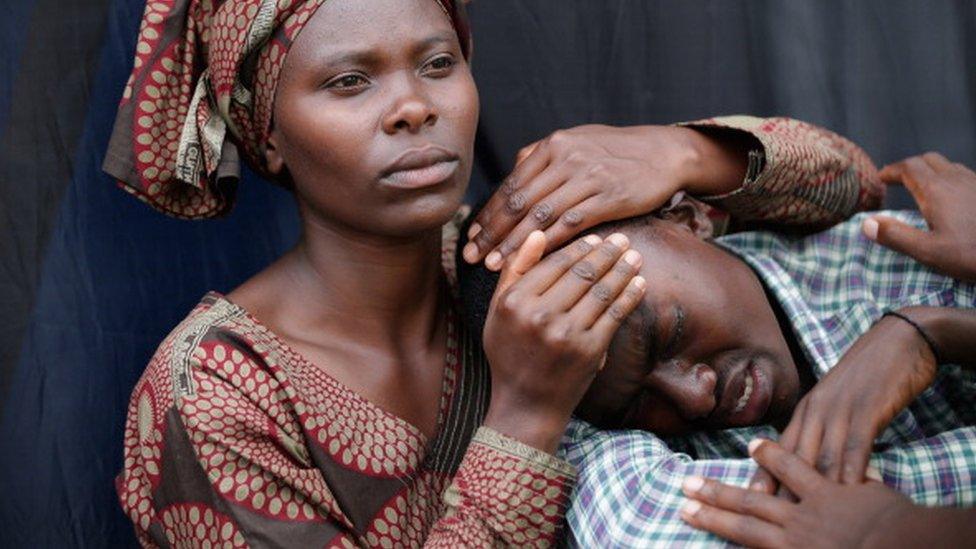

The Rwanda genocide provokes painful memories

The number of people killed in conflicts has declined since 1945.

Fewer died in the first decade of this century than in any decade during the last.

Its peacekeeping operations, which began during the Suez crisis in 1956, have expanded to 16 missions around the world, keeping and monitoring the peace in Haiti to Darfur, Cyprus to the Golan Heights.

The UN has codified a panoply of international laws and forged the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, external.

It has helped broker major international treaties, such as the landmark, nuclear non-proliferation treaty that came into force in 1970, and helped organise historic elections, such as the first presidential contest in Afghanistan in 2004.

United Nations:

Established on 24 October 1945, after World War Two, to prevent another such conflict

There were 51 member states. There are now 193

The headquarters is in New York City, with main offices in Geneva, Nairobi and Vienna

Financed by assessed and voluntary contributions from its member states

Objectives include maintaining international peace and security, promoting human rights, fostering social and economic development, protecting the environment, and providing humanitarian aid in cases of famine, natural disaster, and armed conflict

There are six principal organs: General Assembly, Security Council, Economic and Social Council, Secretariat, International Court of Justice and the United Nations Trusteeship Council (inactive since 1994)

UN agencies include the World Bank Group, the World Health Organization, the World Food Programme, Unesco, and Unicef

The work of UN agencies, much of it unnoticed and unsung, has been impressive, partly because they employ some of the world's leading experts in disaster relief, public health and economic development.

Not only are their staff expert, but often incredibly brave and dedicated.

Partly because of the efforts of Unicef, external, deaths of children under the age of five have declined from nearly 12 million in 1990 to 6.9 million in 2011.

The UN's refugee agency, the UNHCR, external, has helped 17 million asylum seekers and refugees, picking up two Nobel peace prizes, in 1954 and 1981, for its efforts.

The World Food Programme, external each year gives assistance to 80 million people in 75 countries.

Unesco has helped to preserve important sites, such as Machu Picchu in Peru

The preservation of 1,031 of the world's most beautiful sites, from the Serengeti National Park to Machu Picchu, is partly thanks to the cultural agency Unesco.

Its Millennium Development Goals, which will soon be superseded by the Sustainable Development Goals, have been described as the greatest anti-poverty drive in history.

Often, however, the work of agencies is hindered by a lack of funding from member states, which is often called donor fatigue.

There is a chronic shortfall in Syria, for instance, where only 38% of the funding requirements have been met.

Of the $4.5bn needed by the UN to confront the Syrian refugee crisis, only $1.8bn has been contributed.

The UN's convening power, the simple fact that it brings together 193 members, is obviously unique.

Controversial vetoes

Still, all too often its members deliberately hamper its work.

UN agencies would like to deliver humanitarian aid to Syria, to use one example, but for much of the past five years the Security Council has not mandated them to do so.

Russia, with the backing usually of China, has used its veto as a block to protect its ally, Syria's President Bashar al-Assad.

This kind of obstructionism and negative statecraft is common at the UN.

The UN runs the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan

Critics of Israel, a country that regularly complains of being unfairly vilified at the UN, bemoan the regular use of US vetoes to shield it from international criticism.

Often the UN doesn't solve the world's problems, but merely reflects them.

As the late US diplomat Richard Holbrooke once memorably said, blaming the UN is rather like blaming Madison Square Garden when the New York Knicks lose.

It is the players that count, and they who ultimately decide on whether the UN succeeds or fails as a multinational problem-solver.

Syria offers a case study of the UN at its best and its worst.

The deadlock in Security Council has stymied peace efforts, but the UN runs the massive Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan, external, the home to almost 80,000 displaced people.

That camp could never in any way be described as "heaven".

But it has saved those seeking shelter from "hell".