In US, murder masterminds are put to death while killers live

- Published

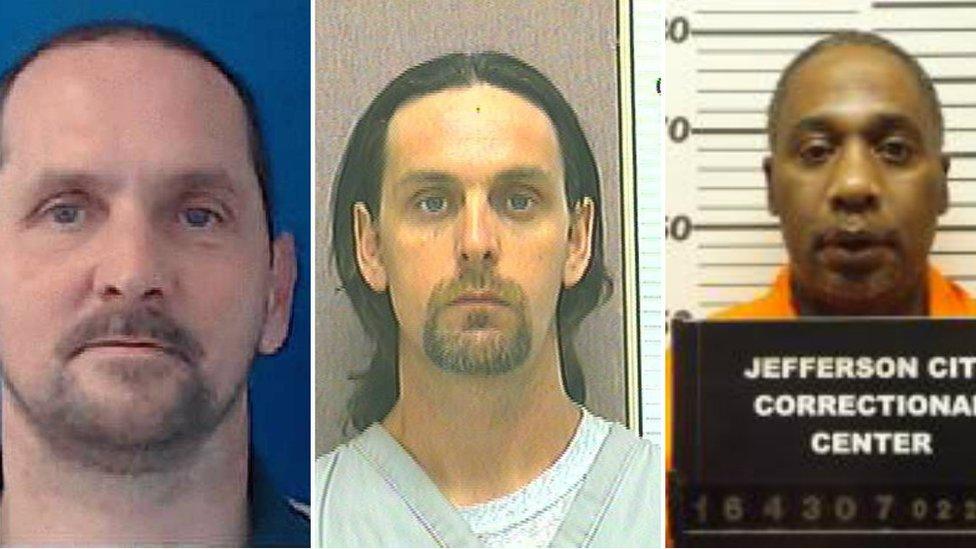

Kelly Gissendaner, Richard Glossip and Kimber Edwards

Three recent death penalty cases have exposed concerns about executing those convicted of planning a murder - especially when the actual killers receive a lighter punishment.

On 7 February 1997, Douglas Gissendaner was kidnapped at knifepoint from his home, driven to a secluded woods and forced to walk to a muddy patch. Douglas - a mechanic and former serviceman in the US Army - was bludgeoned with a night stick, then stabbed repeatedly in the neck and back. His body was not discovered for two weeks.

Kelly Gissendaner was sentenced to death for her husband's murder. On Tuesday, nearly 20 years after the killing, the state of Georgia executed her by lethal injection.

No-one contests that on the night Douglas was killed, Kelly was nowhere near the woods. She was out at a nightclub with friends.

It was her boyfriend, Gregory Owen, who lay in wait for Douglas, marched him into the woods, then left him face down in the mud after stabbing him. Kelly set Douglas up: she and Owen wanted to be free of her husband, as well as cash in his life insurance policies.

During the investigation, Owen testified against Kelly in exchange for a life sentence with the possibility of parole after 25 years.

Before she was executed, Gissendaner's lawyers argued, external that Owen, the actual killer, will be eligible for parole in seven years while she was set to die, evidence of "arbitrary, capricious and discriminatory" application of the death penalty. They wrote that such disproportionate sentencing violated the Eight Amendment, which bars cruel and unusual punishment.

On Wednesday this week, Richard Glossip was scheduled to be put to death in Oklahoma for orchestrating the fatal beating of his boss. The execution was stayed at the last minute, external by Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin.

Next week in Missouri, Kimber Edwards will receive a lethal injection for paying a man to shoot his ex-wife.

Neither Glossip nor Edwards were present for the murders, yet they received much harsher sentences than the men who carried out the killings.

According to Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, capital punishment for proxy murder is very rare. He says only 10 inmates, external have been executed for orchestrating a killing.

But critics say these cases speak to inherent problems in how the death penalty is meted out. Each state has individual laws about what types of murder are eligible for the death penalty - and within those states, similar crimes might be treated much differently depending on the prosecutor.

"The death sentence is considered to be the maximum, the harshest sentence society can impose. If that's going to be justifiable it can only be in circumstances where the person on the receiving end of that punishment is justifiably classified as the worst of the worst," says Keir Weyble, associate clinical professor and director of death penalty litigation at Cornell University Law School.

"Very often we end up in what sure looks to any regular person to be disturbingly disproportionate sentencing outcomes. That is something people should pay attention to."

Gissendaner in 2011, receiving a certificate of theological studies at Lee Arrendale State Prison, in Alto, Georgia

One man paying attention is former death penalty advocate, retired Georgia Supreme Court judge Norman Fletcher.

"In this state, there are judicial districts where the death penalty is rarely if ever sought. And then there are other districts where the death penalty is sought in nearly every case. That just shows how arbitrary is," he says.

"If it's a place where they've got plenty of resources, a district attorney determined to make some big name for himself, they'll seek it in every case."

Fletcher says it is this type of arbitrariness that results in killers getting plea deals and so-called masterminds receiving death. He now wants the death penalty abolished.

While on the bench Fletcher actually ruled that Gissendaner's death penalty sentence was appropriate.

Then he read a post-conviction affidavit, external from Gissendaner's boyfriend admitting that he lied when he said Gissendaner provided him with the murder weapon and came to the scene after Douglas was dead. The affidavit also revealed for the first time that there may have been a third killer whom Owen has never named.

"The system's broke," Fletcher says.

Gregory Owen killed Todd Gissendaner, Justin Sneed killed Barry Van Treese, and Orthell Wilson killed Kimberly Cantrell

In Missouri, where Kimber Edwards awaits his 6 October execution, Orthell Wilson is serving life without parole for the murder of Edwards' ex-wife. Wilson told police Edwards wanted his wife dead because she was going to testify against him in a child support hearing, and Edwards gave Wilson $3,500 (£2,300) to break into her apartment and shoot her.

Edwards initially denied any involvement, then confessed after extended interrogation - a confession he has since recanted, saying it was coerced.

Fifteen years later, in an interview with the St Louis Post-Dispatch newspaper, Wilson revealed that Edwards was not involved in Cantrell's murder.

"Him and I never had that conversation about him trying to kill his wife," Wilson told the reporter, external. "I'm just telling you point blank."

Wilson went even further in an affidavit filed by Edwards' lawyers seeking clemency.

"I alone shot and killed Kimberly Cantrell. At the time of her death, Kimberly and I were in a secret romantic relationship that began after her divorce from Kimber Edwards," Wilson wrote.

"We had a heated argument about my drug addiction and constant need for money and its effect on our relationship. It was this argument that led to me shooting her, an act I regret to this day."

Edwards' attorneys have filed motions seeking to halt his execution based on this late confession by Wilson.

If he fails to earn a stay, Edwards will be the first man executed in Missouri for a contract killing.

There are similar issues at play in Richard Glossip's case in Oklahoma. Hotel owner Barry Van Treese was beaten to death with a baseball bat in 1997 by Justin Sneed, a drifter handyman who was staying at the hotel. But Sneed testified , externalthat Glossip, the hotel manager, put him up to it.

Sneed received life without parole. Glossip has always denied involvement, and Sneed's daughter allegedly wrote an email to the Oklahoma parole board saying that her father wants to exonerate Glossip, but is too afraid of the death penalty, external to do so. Sneed's former cellmates have also given affidavits alleging that Sneed has spoken about framing Glossip, external.

The Oklahoma Court of Appeals denied Glossip's most recent request , externalfor a stay of execution, saying that Sneed's reliability has already been held up in previous court proceedings.

Critics argue that when a prosecutor is willing to play one defendant against the other in murder-for-hire or proxy murder case, it creates an unavoidable incentive to lie.

"It becomes a race to the deal table. The person who gets there first very often is in the position to make the deal, and that deal takes death off the table. That dynamic is fraught with the opportunity for, shall we say, impeding the search for truth," says Weyble.

"If you're facing a death sentence and you're being offered the chance to point the finger at someone else and say, 'Yeah, I did it, but he put me up to it,' that's a pretty powerful incentive."

But some legal experts say that people who organise a murder more than meet the "worst of the worst" definition.

"The hired killer who kills for a living, all things equal, deserves to die. The one who hires them from a motive of greed - that is, to collect an insurance or inheritance - deserves to die," says Robert Blecker, a New York Law School professor.

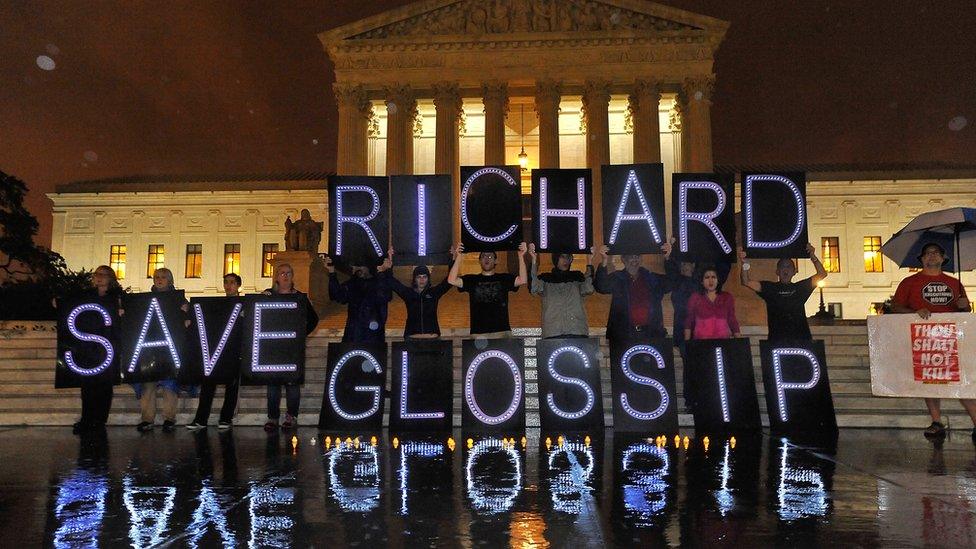

Protesters outside the US Supreme Court on 29 September

Douglas Gissendaner's parents agree. They issued a statement earlier this week asking the public not to forget their son amid the highly-publicised effort to spare the person who conspired in his murder.

"Kelly planned and executed Doug's murder. She targeted him and his death was intentional," they wrote in a statement, external. "As the murderer, she's been given more rights and opportunity over the last 18 years than she ever afforded to Doug who, again, is the victim here. She had no mercy, gave him no rights, no choices, nor the opportunity to live his life. His life was not hers to take."

Just before her death, Gissendaner made a short statement.

"Tell the Gissendaners I am so, so sorry that an amazing man lost his life because of me. If I could take it all back, I would," she said., external

She died singing Amazing Grace.

On Wednesday, Glossip had exhausted his appeals and was moments from execution when Governor Fallin sent word she was granting a 37-day stay. The delay is due to the fact that Oklahoma may have procured the wrong drug for the execution, and has nothing to do with Glossip's possible innocence or sentencing issues.

Edwards is scheduled for a 6 October execution.