Fees, petitions and 'extortion' make getting on US ballots a challenge

- Published

Donald Trump wrote a personal cheque for South Carolina's primary filing fee

All it takes to officially run for the Republican presidential nomination is a one-page form, external sent to the Federal Election Commission, the US government entity in charge of overseeing campaign laws.

That's the easy part. So far this year, 213 would-be commander-in-chiefs have done exactly that, external.

The hard part is everything that comes next.

Announcing one's candidacy, and making it official with federal paperwork, gets a name on exactly zero ballots in the state-level primaries and caucuses that are the key to winning enough delegates to secure the presidential nomination at the Republican National Convention in July.

Qualifying for those ballots is a state-by-state slog, with different rules and regulations for each. It takes time and money - and lots of it. Only the most organised, professional campaigns can manage the task.

For instance there's a $1,000 (£600) price tag, external attached to getting on the ballot in New Hampshire - the early-voting state that has made, and broken, many a candidacy.

That's nothing, however, compared with South Carolina, the third state in the nominee selection process and a battleground for Republican candidates looking to build momentum as the Southern states hold their votes.

To have a shot at winning there, Republicans by Wednesday had to cut a cheque for $40,000 (£26,500) to the state's Republican Party - half of which is passed along to the state government for administrative costs. The other $20,000 goes straight to the party's coffers.

"It's extortion," says Richard Winger, editor of Ballot Access News, external. And it may not even be legal.

In 1972 the US Supreme Court unanimously held, external that a fee of up to $8,900 to run for a local office in the Democratic Party primary was unconstitutional.

"Many potential office seekers lacking both personal wealth and affluent backers are, in every practical sense, precluded from seeking the nomination of their chosen party, no matter how qualified they might be and no matter how broad or enthusiastic their popular support," Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote.

The case speaks directly to fees like the one in South Carolina, says Winger. "I think it's unconstitutional. If all these states started doing this, pretty soon it'd be up to a million dollars."

Many candidates, like Senator Lindsey Graham, turn filing for South Carolina's primary into a campaign event

And South Carolina and New Hampshire are just the start. Eight other states have primaries with filing fees, mostly in the $1,000 range. Arkansas, which holds a primary on 1 March, charges $25,000 - payable by 9 November. Want in on the caucuses in Kansas, external or Kentucky, external? Those will cost $15,000 apiece.

Complicating all this is the fact that filing fees have to come directly from the candidates or their campaign funds - which have maximum contribution limits and strict reporting requirements - not from friends, relatives or the allegedly "independent" Super PAC entities that can raise unlimited amounts of money from deep-pocketed donors to support candidates.

South Carolina's prohibitive amount is said to have helped convince, external former Texas Governor Rick Perry to end his cash-strapped quest for the presidency in mid-September. Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker paid the fee only to drop out the following month. His campaign was reportedly more than $750,000 in debt by the time it folded.

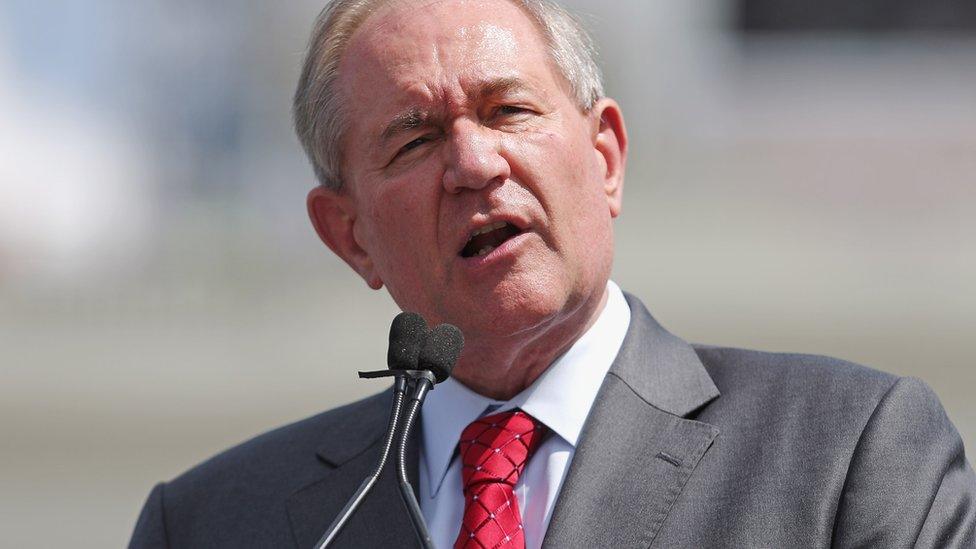

Despite this high bar, no one has stepped forward to challenge the fee in court - and all 15 remaining Republican candidates anted up in South Carolina. Some, like New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, former New York Governor George Pataki and that longest of long-shots, former Virginia Governor Jim Gilmore, filed within days - or even hours - of the afternoon deadline. Everyone, it seems, is content to just sign the cheque and not rock the political boat.

Democrats have their share of fees too, of course, but they're generally much lower. In South Carolina, for instance, candidates like Hillary Clinton will have to pay $2,500 to the state party, which then is responsible for covering the remaining $20,000 to the state for election administration costs out of its own funds.

Scott Walker paid the South Carolina filing fee and later dropped out of the race

Money isn't the only obstacle, either. Many states require candidates to gather up to 5,000 signatures from in-state registered voters - a task that demands a strong national organisation with a motivated volunteer base or the funds to pay professional signature-gatherers to pound the pavement.

In 2012 Virginia ballot-seekers had to hand over petitions with at least 10,000 names - and only two, eventual winner Mitt Romney and libertarian Ron Paul, managed to qualify. Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and former Senator Rick Santorum - each with earlier primary wins under their belts - failed to make the cut.

For the 1 March, 2016, balloting, Virginia has reduced that signatures amount to 5,000, due by 10 December, but at least 200 of those names have to come from each of the state's 11 congressional districts. Many states have similar district-by-district requirements, where the failure to gather enough signatures in even one district will keep a name off the ballot.

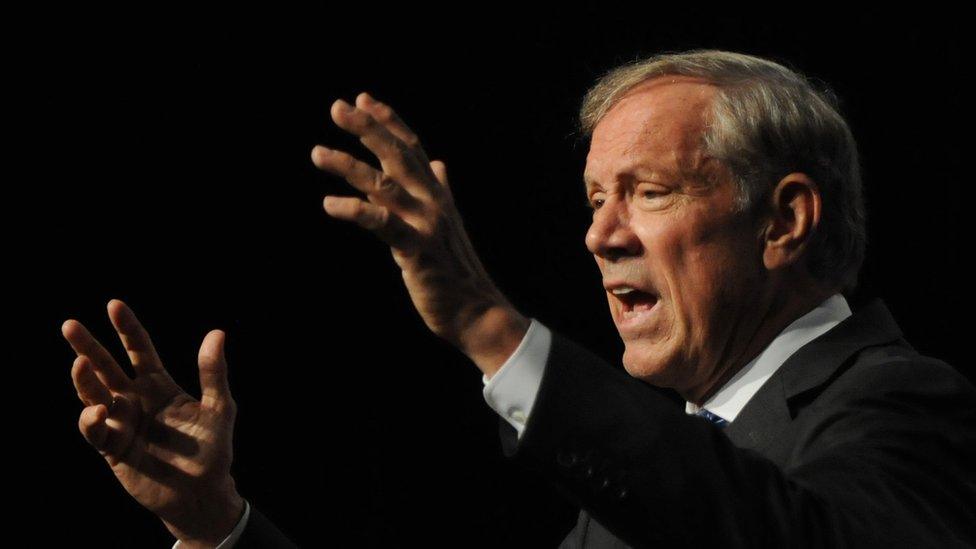

Jim Gilmore, who didn't qualify for the last month's Republican debates, will appear on South Carolina's ballot

Some states give candidates a choice. To qualify for the 1 March primary in delegate-rich Texas, external, for instance, presidential aspirants must either pay a $5,000 filing fee or submit the signatures of 300 registered voters in at least 15 of the state's 36 congressional districts.

Florida, not surprisingly, is a bit unusual, external. Candidates can cut a cheque for $25,000, gather at least 3,375 volunteer-obtained signatures from across Florida or commit to attending the Sunshine Summit - a presidential forum hosted in Orlando by the state Republican Party in November.

That summit could be a big money-maker for the party, which expects to sell, external 2,500 tickets to the event - and is charging, external $200 for a two-day pass and $1,000 for "premium reserve seating" (all major credit cards happily accepted).

George Pataki was the last Republican candidate to announce he was filing for the South Carolina primary

Then there's first-in-the-nation Iowa, which has no petition requirements, filing fees or, for that matter, ballots. Voters can support whomever they please in the caucuses, and if enough likeminded individuals show up to do the same, the candidate will be on his or her way to winning prized delegates.

But then the state's caucus system presents challenges of its own. Getting Iowans to turn out on a cold February weekday and spend an evening singing the praises of their politician can be a logistical effort that makes South Carolina's $40,000 price of admission seem like chump change.

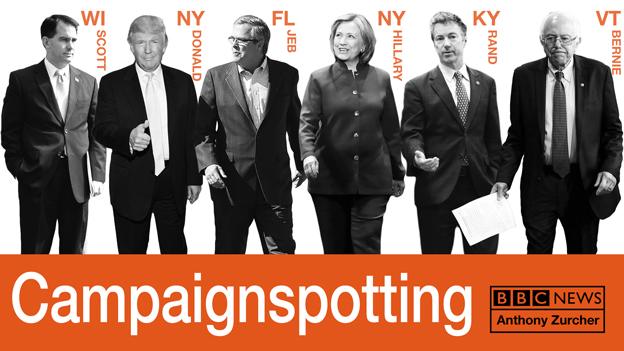

Candidates in (and out of) the Republican presidential field