Could Hillary Clinton face the same fate as David Petraeus?

- Published

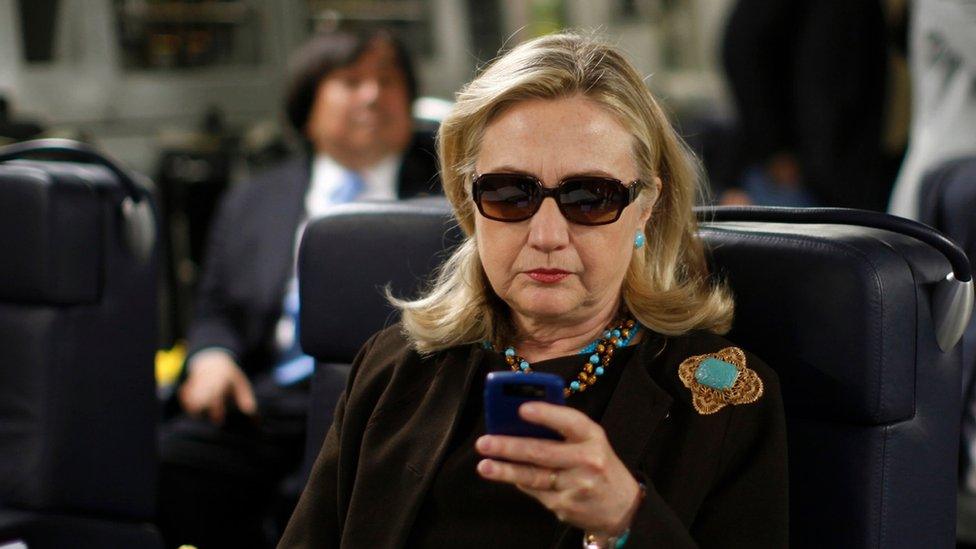

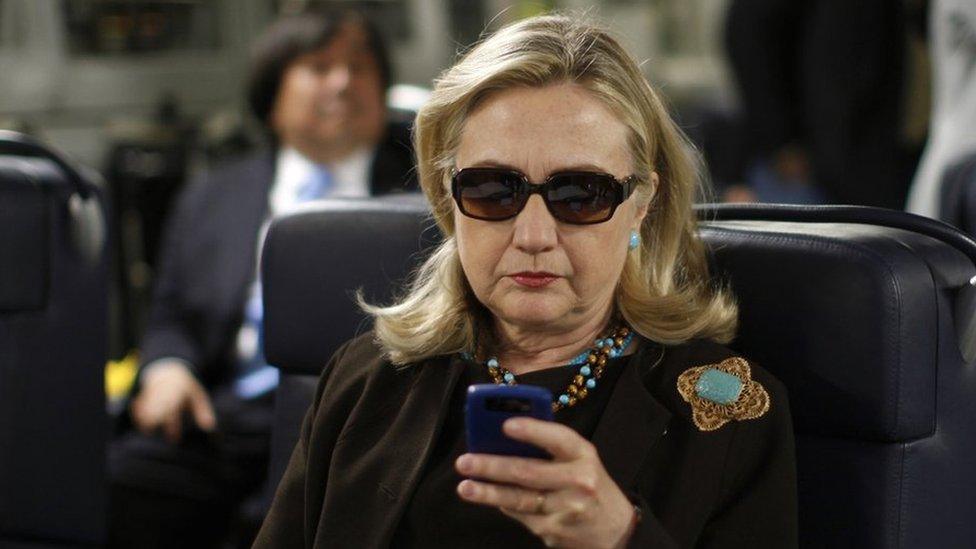

Mrs Clinton used a private server at her house while she was secretary of state, creating controversy afterwards

Could Hillary Clinton's handling of classified information while secretary of state sink her presidential hopes?

It's a question that has dogged her campaign for over a year - but opinions are divided over whether the allegations made against her constitute a crime or are just the latest partisan sideshow.

Perhaps the best way to look at the implications of her case is by considering the context of another high-profile legal drama involving classified documents that was recently resolved - that of former CIA director David Petraeus.

Petraeus pleaded guilty last year to a misdemeanour offence, mishandling classified information, after being accused of handing notebooks with classified information to his biographer-turned mistress, Paula Broadwell.

He was fined and placed on probation - a resolution that some have called a slap on the wrist.

In other cases people who have revealed classified information were sent to prison. In 2009 Stephen Kim, a former government contractor, was sentenced to 13 months for giving classified material to a reporter.

As CIA director, David Petraeus broke the law by revealing classified information

But Petraeus is a high-profile figure. He has been credited with implementing the US military "surge" in Iraq that helped bring stability to the nation - at least temporarily. When President Barack Obama tapped him to head the CIA in 2011, his name was kicked around by some Republicans as a possible presidential candidate in 2012.

His celebrated background has led critics to suggest that there is a double-standard in cases involving the mishandling of classified information - one making it less likely that Mrs Clinton will face repercussions for her actions.

Mrs Clinton used a private server at her house while she was secretary of state, and some of her emails appeared to have contained classified information, though it's unclear whether that information was classified at the time it was sent. Revealing classified information is a crime.

Yet the offence is treated in different ways, depending upon the circumstances. They're also tough cases to prosecute.

Government lawyers have to prove an individual knew what he was doing when he revealed classified information, for example, or that she was unusually sloppy when handling the material.

Petraeus handed over classified information to his mistress, Paula Broadwell

After initially denying any culpability, Mrs Clinton has acknowledged that using a private server at her house was a mistake.

"I should have used two email addresses, one for personal matters and one for my work at the State Department," she said on Facebook in September. "I'm sorry about it, and I take full responsibility."

One of her former aides, Bryan Pagliano, set up the private server at her house. He has reportedly agreed to co-operate with authorities in the investigation. According to the Washington Post, he's been granted immunity.

Officials refused to talk to me on the record about the matter. "I'll leave it to the leakers," Marc Raimondi, the justice department's national security spokesman says.

FBI agents may decide to question Mrs Clinton and more of her aides, both current and former, in the coming months.

The danger for Mrs Clinton's presidential campaign, even if she avoids criminal charges, is that it could play into the perception by some that the former secretary of state can't be trusted.

For conservatives hoping to defeat her in the general election and break the Democrats' eight-year hold on the Oval Office, that's good news. It also makes any discussion of the legal case fraught with political significance.

Every twist and turn in the case, such as revelations this week that one individual had agreed to co-operate with a federal investigation, is scrutinised.

Kurt Volker, a former US ambassador who's now executive director of the McCain Institute, says her actions are potentially worse than anything Petraeus did.

Though Petraeus willingly revealed classified information to his mistress, Mrs Clinton apparently sent email with classified information through a server without proper safeguards. As Volker sees things, the classified material became vulnerable to hackers.

"Everybody and their uncle can potentially see that information," he says. "That means Iranians, Chinese, whoever."

Volker believes she should be punished for her actions and that investigators are doing the right thing in their efforts to find out more about the case.

But he's sceptical about the outcome.

He believes that during an election year, with a Democratic administration in power, she's unlikely to be held accountable for what she did.

"I should have used two email addresses," said Mrs Clinton, answering questions about the server

FBI agents will pursue it as a criminal matter, he says, but he believes that justice department officials will "take into account the political context" (and that Mrs Clinton is a Democratic candidate for the presidency.)

His suspicions about political bias in the White House reinforce a universal truth - campaign season is a time of passion, paranoia and fiery rhetoric.

Few in Washington think that formal charges will be brought against her, however. And if they were, it's hard to see how she'd be sent to prison for committing the same kind of crime for which Petraeus received probation.

If she is charged and avoids any serious penalty, then FBI agents, federal investigators - and plenty of her political adversaries - would have reason to be angry.

"But as far as I can see no crimes have been committed," says Steven Aftergood, the director of the Project on Government Secrecy for the Federation of American Scientists. "So I don't see a place for that sort of frustration."

Like Volker, he sees the issue as political.

"We've been bombarded with accusations before any indictment has been filed," Aftergood says. "And for that reason it seems like a manufactured controversy."

And however you see the politics surrounding the case of Mrs Clinton's email, the controversy is bound to continue - at least until the election.

Follow @Tara_Mckelvey.

- Published9 September 2015

- Published30 January 2016