Michelle Obama’s hashtag quest to rescue Nigerian girls

- Published

Michelle Obama, shown at a panel discussion, was outraged by the kidnapping of girls

Michelle Obama told Americans - and the world - about schoolgirls abducted by the extremist group Boko Haram in Nigeria. But the first lady's awareness campaign has failed - at least in part.

The incident was shocking, even for those who were familiar with stories of extremist violence.

Members of a militant organisation, Boko Haram, kidnapped 276 girls from a school in Chibok, Nigeria, on 14 April 2014.

Afterwards Michelle Obama posted an image of herself on social media, posing with a white sheet of paper that said: "#BringBackOurGirls".

The hashtag campaign, designed to bring attention to the kidnappings, had already reached 1 million tweets by the time Obama joined, but her statement still made a splash. She gave a public address several days later, talking about the kidnappings.

She said her husband was directing the US government do everything possible to help Nigerians bring the girls back.

Many people in the US who hadn't heard about the kidnappings - or weren't aware of Boko Haram - suddenly were.

And now that the first lady was involved, calling for their return, the Nigerian schoolgirls seemed to have a better chance at freedom.

On Wednesday, nearly two years after the abductions, Obama spoke about the girls during an event about education at the World Bank in Washington.

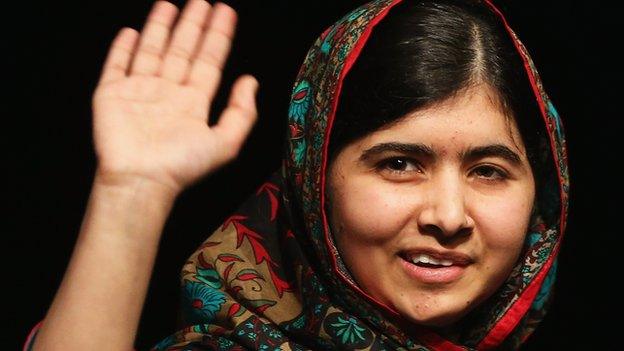

Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani education activist, rallied on behalf of the girls

Before Obama appeared at the podium, the World Bank's president, Jim Yong Kim, announced that the bank group was investing $2.5b (£1.76b) in girls' education projects around the world.

Then Obama spoke about her initiative, Let Girls Learn, that promotes education for girls.

Prime Minister David Cameron has joined her effort, creating a US-UK partnership that devotes $200m to girls' leadership camps and other programmes.

She's said, external in the past that she put the Let Girls Learn initiative together in part because she was disturbed by the story of the kidnapped schoolgirls.

In her speech, though, she mentioned them only briefly.

"Why, two years ago, would terrorists be so threatened by the prospect of girls going to school that they would break into a dormitory in the middle of the night?" she said, describing the crime.

Beyond that she didn't say much about the girls - and didn't talk about their fate, either.

Fifty-seven of the girls escaped from Boko Haram. The rest are still missing, with little hope of returning to their previous lives.

Obama once described it as an "unconscionable act". Like people around the world, she was outraged.

Angelina Jolie has called for people to help the Nigerian schoolgirls

The awareness campaign - the one that was designed to save the girls - had a star-studded cast.

Besides Obama, Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani education activist, spoke out on behalf of the girls. So did filmmaker and activist Angelina Jolie.

Yet the US effort - and impact - was minimal. Obama said Americans would help the Nigerians.

With that goal in mind, the US sent several dozen Air Force personnel to the region to use drones to help find the girls, reported, external the New York Times.

In addition a couple dozen Americans gave advice to Nigerian officials who were trying to save them.

At one point authorities found them. But as Andrew Pocock, who served as British high commissioner to Nigeria, explained in the Sunday Times, external, they didn't rescue them.

People could have been killed - possibly even the girls themselves.

"It's a tragedy," said Shiv Srikanth, natural-disaster risk-management analyst who works in the World Bank and came downstairs to see Obama.

"But I don't know - the White House has its own restraints on what it can and cannot do."

At the World Bank, Obama talked about "moral vision" and the need for girls around the world to be educated.

She said: "These girls are our girls - every last one of them." She described children around the world as "our responsibility".

She stood in a foyer with a glass ceiling thirteen stories above her showcasing a turquoise-blue sky. Natural light flooded the building, reflecting off floor tiles.

Economists, development experts, and gender-violence researchers cheered as she spoke. They were part of a global do-gooder scene that seemed unusual in button-down Washington.

One man carried a motorcycle helmet, and a woman had five long braids, with three falling down her back.

One of the bank executives, a man in dark-framed glasses, sat on a bench as a soundtrack played. The music included bird songs and tracks from Fleet Foxes, a pop-folk band.

"It makes me feel like dancing," he said.

Despite initial outrage and a humanitarian spirit, the first lady's campaign to tell the world about the kidnapped schoolgirls - in the hope they'd be saved - ultimately failed.

In retrospect, the public-awareness campaign seemed a little dreamy.

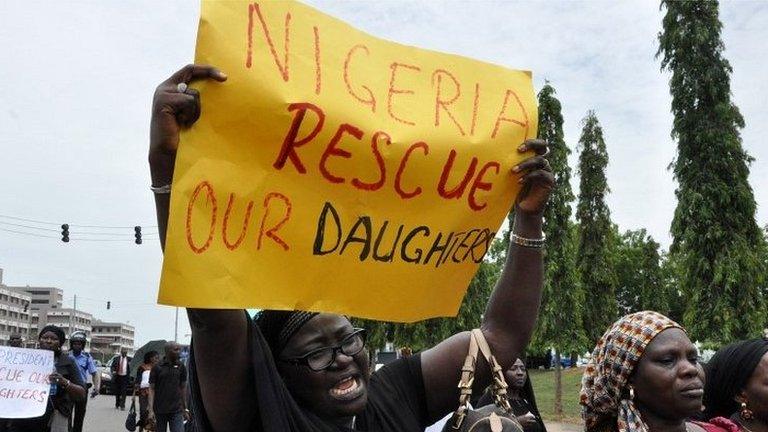

A South African girl, shown in 2014, called for the girls to be freed from Boko Haram

"What are the odds that Boko Haram is going to change their minds?" said Fait Muedini, who teaches at Butler University in Indianapolis and writes about Islamist groups.

Adam Mugume, a research director for the Bank of Uganda and a member of Obama's audience at the World Bank, said he was impressed with her effort to draw attention to the issue of Boko Haram.

Still the problem of violent extremism in Africa is deep. "You can't fix it from afar," he said.

In the two years since the girls were kidnapped, thousands of other children in the region have also disappeared, according to a recent Unicef report, external.

In order to show commitment to Boko Haram, boys attack their own families. Girls are forced to carry suicide bombs.

In the movies Americans swoop in and take care of things.

"People ask me: why doesn't the US send in special forces like in Zero Dark Thirty?" said Brandon Kendhammer, a professor at Ohio University in Athens who writes about Boko Haram.

But in real life US power - like hashtag activism - is limited.

The first lady's impulse to help the girls was understandable - and "very human", as John Campbell, a former US ambassador to Nigeria, told me.

"That is a very different thing from someone deciding to send American troops," he said.

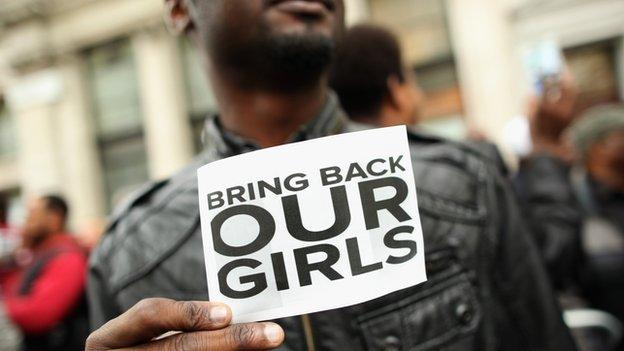

In London and around the world, people have fought to save the schoolgirls

He added: "You recognise sometimes there are situations you just can't solve."

Kendhammer said: "We like to feel that the stuff we do matters," he said.

Still as he pointed out: "Americans knowing about something is not enough to make it better."

With hashtag campaigns, people click and feel better. Mostly they forget about the whole thing. But not always.

Obama joined the campaign - and created a global initiative to educate.

Most of the Nigerian girls she tried to save will never finish school. But because of her efforts, other children will.

Follow @Tara_Mckelvey on Twitter.

- Published12 May 2014

- Published20 July 2015