Clinton crime bill: Why is it so controversial?

- Published

A 1994 federal crime bill passed by former President Bill Clinton has become a problem for Hillary Clinton's campaign. But what did it actually do?

The crime bill in question is the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, external, an enormous $30bn (£21bn) package that was the largest crime-control bill in US history. Critics say the bill decimated communities of colour and accelerated mass incarceration. Proponents say it contributed to the precipitous decline in violent crime in the US that began in the mid-1990s.

So who is right?

1. What was the 1994 Crime Bill?

The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act was a lengthy crime control bill that was put together over the course of six years. Its provisions implemented many things, including a "three strikes" mandatory life sentence for repeat offenders, money to hire 100,000 new police officers, $9.7bn in funding for prisons, and an expansion of death penalty-eligible offences. It also dedicated $6.1bn to prevention programmes "designed with significant input from experienced police officers", external, however, the bulk of the funds were dedicated to measures that are seen as punitive rather than rehabilitative or preventative.

Then-President Clinton signed the bill with the support of First Lady Hillary Clinton.

2. Why was it passed and who supported it?

At the time, violent crime was seen as out of control in the US. Starting in 1987, the homicide rate, external in the US was increasing by 5% each year, peaking in 1991 with 9.8 deaths, external per every 100,000 people. Many of those victims were young African Americans. Robbery and assault rates had exploded beginning in the late 1960s, and the crack cocaine epidemic was devastating the nation's urban centres.

The bill had bipartisan support, and easily passed both the House and Senate. The Clintons have pointed out that both black politicians and community leaders backed the law, and in general supported increased law enforcement in order to help quell street violence destroying communities.

But a recent New York Times op-ed, external calls this a "selective hearing" of what African American leaders were asking for and points out that members of the Congressional Black Caucus asked for provisions in the bill that were left out.

"Policy makers pointed to black support for greater punishment and surveillance, without recognizing accompanying demands to redirect power and economic resources to low-income minority communities," according to the piece, written by three Ivy League professors of history and African American studies. "When blacks ask for better policing, legislators tend to hear more instead."

3. Did it cause mass incarceration?

No. But many believe that it may have amplified effects that were already under way.

Historians point out that there had already been decades worth of punitive crime control laws that ramped up the rate of incarceration in the US, including the Ronald Reagan Anti-Drug Abuse Acts which established mandatory minimum sentences for drug possession, or Lyndon Johnson's Safe Streets Act of 1968, which increased the flow of federal money to local and state police. Many pieces of punitive crime legislation pre-dated the 1994 bill, on the federal, state and local levels. The prison population had tripled in the two decades that preceded the act.

"The feds are very much a reactor in criminal law, not a creator. Much of this was already well under way," says John Pfaff, professor of law at Fordham University, who argues the actions of local prosecutors are a better starting point when tracing the roots of mass incarceration.

The 1994 crime bill's sentencing guidelines also only applied to those charged with federal crimes. The vast majority - an estimated 87% - of the country's prison population is housed in state prisons. However, in the 22 years since the bill was passed, the federal prison population more than doubled, external. In 1994, the Bureau of Prisons held 95,162 inmates; today that number is 214,149.

The bill did attempt to incentivise states to pass tougher sentencing laws by offering up additional federal dollars, but Pfaff says only a handful of states, external took advantage of that.

At minimum, says Marc Mauer, executive director of The Sentencing Project, the bill reinforced the popular thinking that the solution to crime was harsher punishments.

"This was a national bill, it got an enormous amount of attention at the time," he says. "I think it very much helped to solidify the 'tough on crime' movement."

4. Did it cause the precipitous decline in crime that began in the 1990s?

Mr Clinton said at one point the 1994 crime bill caused "a 25-year low in crime, a 33-year low in the murder rate". That is probably not true, though the causes of the drop in crime have puzzled academics for years.

By the time the crime bill was passed, violent crime had begun its decline in the US. It would continue to plummet throughout the 1990s before levelling out in the early 2000s. Crediting a single piece of federal legislation is a stretch, says Mauer, and furthermore, the White House should have taken the decrease in crime rates that was already happening into consideration when it drafted the bill.

"We couldn't know then how much [the crime rate] would go down, but there should have at least been some recognition of that before jumping on this 'tough on crime' bandwagon," he says.

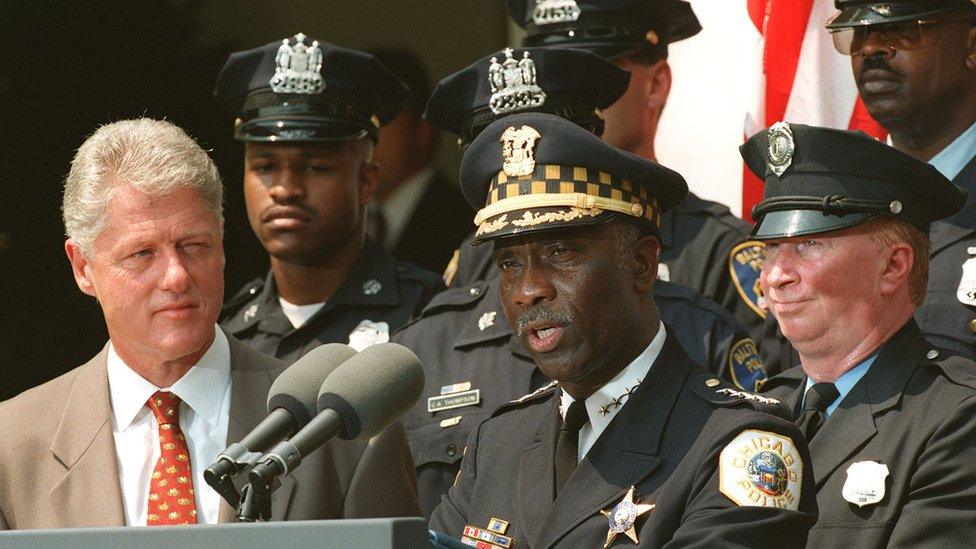

Clinton signs the "One Strike and You're Out" policy

5. What effect will the bill have on Hillary Clinton's legacy and her bid for the presidency?

Hillary Clinton has already admitted that the 1994 bill went too far. She apologised for her use of the term "superpredator", external when referring to a supposedly new kind of remorseless juvenile criminal that ultimately never emerged. She has spoken repeatedly on the campaign trail about ending mass incarceration. Her platform promises, external to make the Fair Sentencing Act retroactive and to reduce nonviolent drug crime mandatory sentences.

But other policies enacted by the Clintons had detrimental effects for communities of colour and former inmates returning to society, even if they did not directly cause mass incarceration. One part of the Crime Bill stripped all Pell Grant funding for college education for prisoners, even though education is now seen as an effective tool against recidivism. President Clinton championed a "one strike, you're out" policy for evicting public housing tenants if they or their guests were involved in any criminal activity, causing a jump in evictions and making it more difficult for former inmates to find housing.

When the 1994 Crime Bill was being drafted, Elizabeth Hinton, assistant professor of history and African and African American studies, says that the US Sentencing Commission already knew that punitive criminal control and prison policies were disproportionately affecting people of colour. That, she says, is what people should make a note of when deciding whether Mrs Clinton still should pay a political price for the policies of the 1990s.

"Part of this is not just reckoning with the Clinton legacy, but reckoning with the policy choices that both Democrats and Republicans have made since the Civil Rights Movement - replacing social welfare policies with punitive measures," she says.

"The Clinton administration knew that the criminal justice system was deeply unfair and biased against African Americans, and chose to expand that system."