US election: Under the skin of Trump country

- Published

Donald Trump stunned the political world by storming the primary contests to become the Republican Party's nominee for president. And one county in the key battleground state of Virginia offers some answers as to how he did it - and why so many people want him rather than Hillary Clinton to be the next resident of the White House.

If the sun is shining down on the verdant hills of Henry County, Virginia, chances are that Janice Merkel can be found on the side of the road somewhere, waving at the traffic from a lawn chair under a giant sign: "TRUMP GEAR".

On a sweltering day in early July, she sits just feet from the traffic hurtling past in front of a motorcycle shop. Truckers blast their horns in approval as they thunder past.

"I've noticed a shift, I'm getting more honks and waves," says the 48-year-old mother of two. "I'm actually disappointed I'm not getting flipped off."

Since she began selling six weeks ago, Merkel has become something of an unofficial pollster for the people who stop to peruse her selection of (unofficial) Trump T-shirts and hats emblazoned with slogans like, "Build That Wall" and "Finally Someone With Balls".

Janice Merkel says she gets plenty of love at her roadside Trump gear stand

"The main viewpoint is they just don't want Hillary," she says. "That is the biggest comment. We just have to get rid of Obama, we have to get rid of the Clintons. And they'll vote for Trump just to get rid of her."

The people of Henry County - hundreds of miles away from the increasingly Democratic-leaning parts of northern Virginia closer to Washington - have long memories. They remember the heyday of the local economy in the 1960s and '70s, when there were so many manufacturing jobs that you could quit one in the morning and have another by after lunch, as the local saying goes.

But then came globalisation, the North American Free Trade Agreement - ratified by potential first husband, former President Bill Clinton - and the textile plants and the furniture factories packed up for Mexico or went belly up. Unemployment hit 20%. When the US was declared officially in a recession, external in 2008, Henry County residents grumbled that they'd already been in one for 10 years.

Today, some locals would dearly love to stop bemoaning the job losses and the empty factories, which at this point have been shut so long an entire generation has grown up never knowing what it was like when the area was booming. But locals have yet to forgive the Clintons.

"No way I'd vote for Hillary Clinton," says Andy Turner, a cemetery owner who drops by Merkel's stand to buy two Trump yard signs. "If she was running by herself it just wouldn't happen."

"Buddy", a 69-year-old Vietnam veteran, says he would never vote for Clinton

"I'd vote for the devil before I'd vote for her," says Buddy, a white bearded veteran who rode up on a gleaming purple Harley Davidson.

Merkel calls all her customers "sweetie" and sends them off with a promise to "tell everyone" that she's here. She is proud of her salesmanship, but admits she would prefer a full-time job with health insurance. The Trump job is by its nature temporary, and she has a chronic health condition that requires expensive medication.

Although she voted for Obama the first time, she says he lost her support because of the Affordable Care Act.

"You're working close to minimum wage and yet you're still supposed to have insurance - how?" she asks. "I am one of the poorest of the poor."

When she arrived in the area 11 years ago, Merkel says she was fleeing an abusive marriage in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, with her two young sons in tow. She struggled to start over from nothing in an economically depressed area. Unable to find a job doing administrative work in an office, she worked at a tyre shop for roughly minimum wage.

Despite all that, she is optimistic about her future, especially now that her two boys are grown and "excelling" at the local community college. When she talks about her hope that Trump can bring the country "back" she transitions almost seamlessly into her own personal story.

"I was just making ends meet, but I raised two really great kids," she says. "I'm back to being what I used to be prior to my husband - that go-getter. That 'I'm not going to take anything from anybody' person again.

"It's great to be back. To have me back."

More on Clinton v Trump

Eight years ago, when Merkel voted for Obama, he held a campaign event at an automotive warehouse in Martinsville, the seat of Henry County, and told the crowd, external, "I will wake up in that White House thinking about the people of Martinsville and the people of Henry County, and how I can make your life better."

But eight years later, Merkel is still poor. She is still under-employed. For years, state and national politicians have used Martinsville as a backdrop to launch their campaigns promising new jobs. Their failure to deliver has left the residents numb and disillusioned.

Few residents have forgotten that at a 2008 campaign event, then-Senator Obama promised to "wake up in that White House" every day thinking about Martinsville

"The average person who has been hurt the most by the way the global economy has changed hasn't seen a lot of change in Washington or a lot of benefit in their own personal lives," says Max Hall, a middle school teacher. "Around here people blame Nafta, they blame the World Trade Organization - it's all different faces of the same trend which is globalisation and I think that's what's driving all of this."

This is the appeal of Trump, the non-politician, the businessman who promises to renegotiate our trade deals and reign in currency manipulation by countries like China. Indeed, in national polls, Trump was seen as the candidate who can better "handle the economy", external. Henry County rose to prominence thanks to small businessmen and Trump supporters would rather put the country in his untested hands rather than trust a lifelong politician whose husband played a direct role in the decline of their local economy.

To Merkel and others like her, Trump's message is not about fear or isolationism. It's a message of hope.

"He's standing up for those who can't," she says. "I really believe Trump can bring back some business to America, get people working again, give them a reason to get up in the morning. Take pride in themselves again, because they can get off the system, they can make it. They can do it."

Martinsville Speedway has become an affordable 4 July tradition for local families for 18 years

On race days at the Martinsville Speedway, a paperclip-shaped Nascar track dubbed the "half mile of mayhem", the population of the area temporarily triples - the grounds behind the track fill up with camping tents and every hotel is booked.

But on the 4 July, the track shuts down and a stage is erected on the finish line. Big name country music acts play before a huge fireworks display - this year the performer is the Gatlin Brothers. Outside the stadium, a miniature carnival springs up, with bounce houses and a small Ferris wheel. Everything is free, paid for by a pool of 40-50 local businesses.

"When we were growing up as kids, a family could still afford to maybe go to the beach or for a long weekend for Fourth of July," says Jeb Bassett, who fundraises for the event. "[Twenty years ago,] the economy just wasn't what it had been. Families couldn't afford to take a vacation, so we wanted to continue the celebration."

This year, as the stands begin to fill, Martinsville Mayor Danny Turner is glad-handing near the stage when a man excitedly taps him on the shoulder, mistaking Turner's cap for one of Trump's "Make America Great Again" hats. The man leans down toward a tiny boy at his knee - his great grandson - and asks who he's going to vote for.

"Trump!" the boy squeaks. Turner chuckles.

All the rides are free on 4 July

Mayor Turner is a gregarious retired United Parcel Service employee who has lived in Martinsville all his life and knows all of its quirks - that a 1939 Buick that survived the attack on Pearl Harbor without a scratch is parked in a garage somewhere in town, or that when President Obama last visited he allegedly skipped out on a $63 tab at a local restaurant (a White House official says there is "no reason to believe that the President skipped paying the bill", though the restaurant stands by the story).

Turner is also a lifelong conservative and a Trump supporter, albeit a pragmatic one - his typical observation on the candidate is: "I just wish he'd shut the hell up."

He's not alone. Brad Parker, a staunch conservative and one of many local business owners who plans to vote Trump, agrees that the candidate often goes too far.

"What I don't like about Trump is his stand on minorities," says Parker. "I hope he was just saying that to get to where he is today, but he said some things recently that has given me some doubts about whether he can ever separate himself from those racist comments."

Parker says that if Trump's rhetoric gets too extreme, he will just stay at home on election day - he refuses to vote for Clinton.

Over and over again, Trump is described by people there as the "lesser of two evils".

"Donald Trump has got everybody scared," says Turner. "These are absolutely the two worst possible candidates."

Taking a stroll outside the Speedway stadium, he runs into a former schoolmate named Ronald "Cotton" Emerson. Emerson is also a Trump supporter for one reason - bringing back jobs.

"It got to the point where here I am, 58 years old now, nobody will say this, but nobody wants to hire me at this age," says Emerson.

The ruins of a former furniture factory in Martinsville

"A man's worthless once he's about 52," says Turner. "Worthless."

It is easy to find men and women like Emerson, who can rattle off a long list of former employers. The region was known as the "sweatshirt capital of the world" and the saying goes it was home to more millionaires per capita than any place in the country.

"It was the manufacturing powerhouse of the whole state," says Beth Macy, author of Factory Man, a profile of one of the local furniture manufacturing families that has been optioned for a film version by Tom Hanks. "The speaker of the house was from there … the whole place just had a lot of power in the '60s."

The textile factories began going to Mexico after the implementation of Nafta in 1994. Five years after Bill Clinton signed the deal, an estimated 2,600 Henry County residents were unemployed.

Hillary Clinton and Nafta

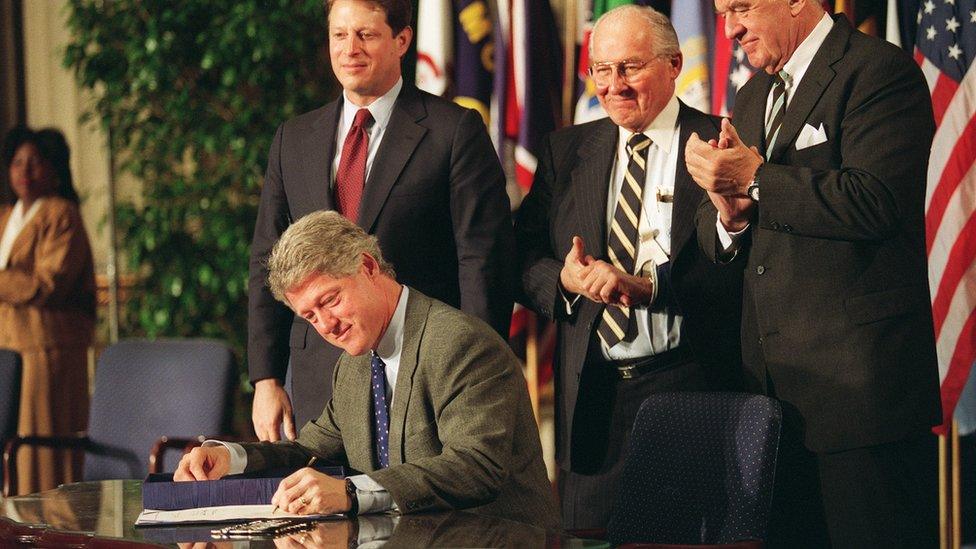

Bill Clinton signs Nafta on 8 December 1993

Nafta disintegrated tariffs and other trade barriers between the US, Mexico and Canada

Brokered by President George HW Bush but signed into law by President Bill Clinton in 1993

Hillary Clinton spoke favourably of the deal in its early days, saying it was "proving its worth", external

Although some economists argue Nafta was a net positive for the US, manufacturing towns like Martinsville disproportionately felt the brunt of job losses when companies moved to Mexico

In 2008, Clinton said Nafta had "hurt a lot of American workers", external and she had been "a critic of Nafta from the very beginning"

She is now critical of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Obama's free trade agreement between the US, Japan, Mexico and nine other countries

Says she will "level the global playing field for American workers and manufacturers"

And wants to spend $10bn on US manufacturing to discourage outsourcing

Once Chinese manufacturers began producing cheap furniture, the local family-run companies like Hooker, Stanley and Bassett furniture began lay offs and plant shut downs too.

But things are not as bad now. Unemployment has decreased to about 6%, though that is at least in small part because many have stopped looking for work. The population of the area has also decreased, bobbing along at just under 14,000.

According to Angeline Godwin, president of the Patrick Henry Community College in Martinsville, this past year she had only a single student paying tuition on Trade Act funds, allocated specifically for people who had lost their jobs to international competition.

"That's a good thing, because it means we're not having plant closures," she says.

Before making his appearance at the Speedway, Mayor Turner took a drive around Martinsville, past the burned down furniture factory where his father worked, and points out a modern, low-slung building marked Eastman Chemical Company.

Mayor Turner helped restore the voting rights of Mellissia Jennise Giles after she lost them because of an old felony conviction

"In Martinsville, they make 40% of the window film in the world, supposedly - they're a success story," he says as the car rolls past. "Alcoa just has bought this place over here at the top - it's a titanium factory, brand new... this is one of the largest beef jerky places."

The plants are smaller, there are fewer jobs and many require a higher skill level, something Turner says the area has lost in the "brain drain" that accompanied the economic recession.

Turner has high hopes that the widening of the Panama Canal , externalwill bring logistics jobs to Martinsville, thanks to the town's proximity to the Port of Virginia and Port of Savannah.

"I see an area that Nafta killed and international trade bringing this area back," he says.

Back at the Speedway, Turner's vice mayor Jennifer Bowles arrives. A 26-year-old political newcomer, Bowles is in many ways Turner's political opposite and recently endorsed Hillary Clinton in the local newspaper.

The pair say their working relationship has been good, and they often appear at events together. Although divisions between Democrats and Republicans seem to never have been deeper in this election season, Turner and Bowles don't have the option of vitriol in a small town.

"We all want what's best for Martinsville. So it's easier for us to agree," says Bowles. "When it comes to national politics, that's when it gets really, really complicated."

Uptown Martinsville

As the fireworks are exploding over the Martinsville Speedway, 26-year-old Eli Salgado is several miles away, drinking a beer with a friend at one of the town's popular Mexican restaurants.

"I notice not many Mexican people go," he says of the Speedway celebration. "They just celebrate with their families."

Salgado was brought into the country illegally from Mexico when he was four, but he was granted Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (Daca) status in 2012.

He is a student at the local community college, and says he actually quit his job as a machine operator in a warehouse in order to take more classes and finish his degree just before the election - in case Donald Trump takes the White House.

"If they were to take away Daca, I wouldn't have it for next year, fall term," he says. "I'm just not willing to take that chance."

While Henry County is 72% white, the city of Martinsville is very diverse - almost half white and half black, with a small Hispanic population that migrated to the area when jobs were plentiful. The city may actually go Democratic in the coming election, though the county - which has about three times the population of the city - is firmly Republican.

Liberals like Salgado don't think the resonance that Trump is having locally is colour-blind. In a former slave-owning area, the topic of race is never far below the surface, especially in an election where polls show voting is will go along race lines, external - black and Hispanic voters for Clinton, and white voters for Trump, though - again, not even her own supporters in Martinsville are overly enthused by Clinton.

"It's because of her husband and that damn Nafta. She needs to realise that Nafta ruined us," says Naomi Hodge-Muse, leader of the local chapter of the NAACP and a Bernie Sanders supporter who has switched her allegiance to Clinton. "Hillary does not inspire. She does not pull. That last name actually hurts her."

Hodge-Muse doesn't buy her friends' and neighbours' arguments that a vote for Trump says nothing about race - she thinks they just don't want to admit they're being manipulated by barely concealed racist rhetoric.

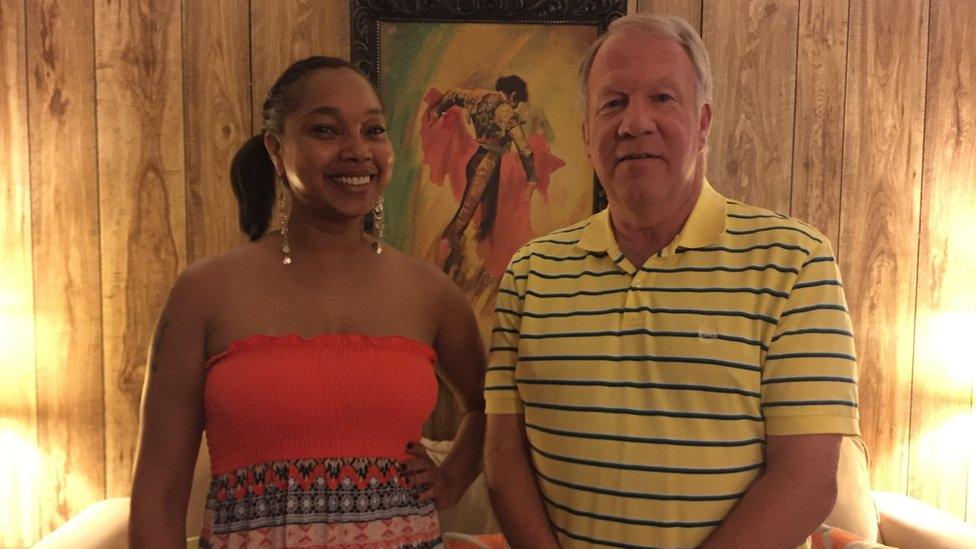

Naomi Hodge-Muse (left) says she will vote for Clinton - but isn't excited about it

"We're used to code words - we understand the code," she says.

According to Terry Smith, a professor of political science at Patrick Henry Community College and a lifelong resident of Martinsville, other social issues like abortion and gun rights can't be dismissed when explaining how Henry County turned from solidly Democratic to solidly Republican, especially in a deeply religious community that is still predominantly Southern Baptist.

"I think people started to view Democrats as too liberal or certainly more liberal on those issues," he says.

For voters like Joe Bryant, a small business owner and a member of the Henry County board of supervisors, those social issues make his decision to vote for Trump easy.

"I'm pro-life. I don't like abortion at all… I love my guns, the Second Amendment is heavy on me," he says. "Donald Trump, I think if he could just learn to control his tongue - but I think that's what people like about him."

Despite dramatic difference of opinions, Martinsville and Henry County is the kind of place where liberals and conservatives live and work together, and end up - occasionally - coming to understand each other's perspective.

Two years ago, a successful industrialist from Melbourne, Australia - who asked that the BBC not used his name - moved with his family into a stately mansion once owned by one of the area's most prominent furniture families. Since moving in, he says he tries to avoid talking politics, fearing his left-of-centre views might not endear him to his new neighbours.

But three weeks ago, he felt compelled to compose an email to likeminded friends in Europe and Australia. The subject line read "Shovelling Gravel".

The owner of this majestic acreage says one of his gardeners changed his perspective on Trump

"Today [I] had one of my gardeners resign, no idea why. Perhaps it was shovelling gravel for eight bucks an hour," he wrote. "He was 61, he did have a middle management job at Nabisco for 22 years (he looked and sounded like a CEO).

"He had done everything right in his life - went to college, got a good job, paid for his kids to go to college, paid his health insurance, went to church on Sundays … he is basically struggling."

The email concludes, "This is why Donald Trump's bizarre rantings resonate with so many people."

The Australian homeowner said that though he once thought Trump's popularity was fuelled only by ignorance, he's come to understand the phenomenon in a totally new light.

"I guess my opinion has changed just from being in this area. When you see how, I guess, disillusioned [people are] or you see certain areas of America have missed out on prosperity," he says.

"Everyone has a story really. That's just one of them."