Firefighting blamed for 'megafires' ravaging US forests

- Published

They're known as "megafires", and they're becoming increasingly common and destructive in the wildlands of the western United States. Could overzealous firefighting itself be to blame? BBC North America Correspondent James Cook investigates.

In a quarter of a century as a firefighter, Mark Hartwig has seen more than a few wildfires.

But as the years roll by, the San Bernardino County fire chief says the blazes are becoming tougher to tackle.

"There is no doubt that fire intensity is increasing in Southern California," Mr Hartwig says as he heads out to inspect the front line of yet another inferno that has taken hold in the mountains east of Los Angeles.

"We used to have a thing called fire season," he says.

Now, "fire season is year round".

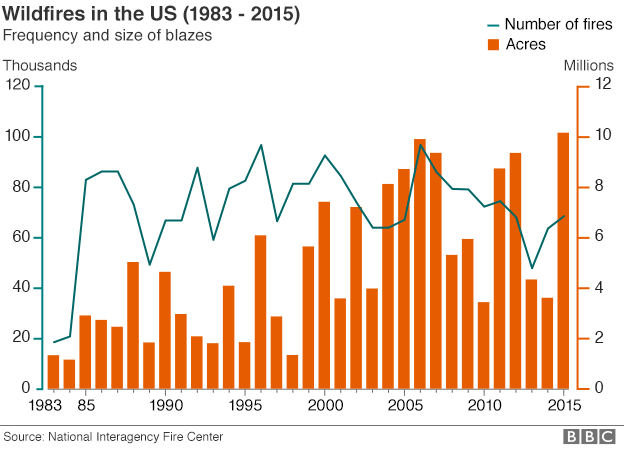

The results are devastating. The amount of land laid waste by wildfires, not just in California but across the United States, is rising.

From 1983 (when modern records began) to 1999, the total area burned annually by wildfires, external exceeded five million acres just three times.

But at the turn of the century, the destruction accelerated, with wildfires scorching more than five million acres in 11 out of the 15 years between 2000-2015.

How to stop megafires: Let some of them burn

In 2015, the figure topped 10 million acres, a record in recent history.

The challenge this poses, and the near constant battle against these blazes, makes it difficult to pause and take stock.

Fires make for dramatic television pictures, and reports on the evening news focus on the human tragedy of lives and homes lost, and the bravery of the men and women trying to bring them under control.

There is much less public discussion about what is driving these towering, terrifying conflagrations. But many scientists, foresters and firefighters think they know what is going on.

One cause of major wildfires is obvious - rising temperatures have resulted in tinderbox conditions across much of the American west, not least in California, now five years into a punishing drought.

When fire breaks out, whether through lightning, accidents or arson, it races through the parched passes and canyons at deadly speed.

However, another possible cause is far more surprising - it turns out that firefighting itself may be to blame.

"We are caught in this vicious circle," says Tom Fry, western conservation director for the American Forest Foundation, a non-profit group which seeks to represent some 11 million private and family landowners whose holdings cover an estimated 56% of all US forest.

"The forests need fire," he insists.

"Fire is as natural to a forest as sunshine and rain, and yet we can't have fire in our forests because of the population pressures and the unhealthy condition of the forest."

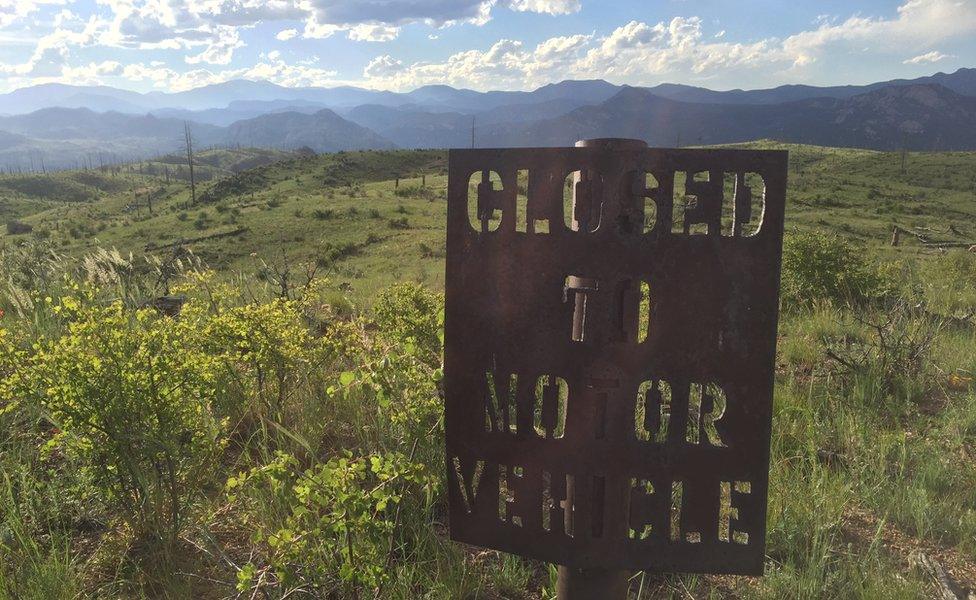

Mr Fry is standing in the middle of a landscape which makes his point for him, in a giant scar which cuts through the middle of the Pike National Forest in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, south west of Denver, Colorado.

The Buffalo Creek fire scar

Twenty years ago, the Buffalo Creek wildfire raced through here, the result of an unattended campfire driven by fierce winds.

It was a crown fire, meaning it burned ferociously to the very tips of the pines, sending flames hundreds of feet into the air, the blaze itself leaping from crown to crown of the trees.

The Buffalo Creek fire consumed nearly 12,000 acres in under five hours. There was little firefighters could do but watch it burn.

The intense heat baked the soil, leaving it slick and unable to absorb moisture from a huge thunderstorm that followed two months later.

The result was deadly flooding, catastrophic damage, and mountains of silt and debris washing into a reservoir which supplied much of Denver's drinking water, dramatically reducing its capacity.

War with wildfires

The city is still counting the cost of dredging the reservoir, which ran into many millions of dollars.

"It will take centuries for this burn scar to heal over," says Mr Fry.

He believes Buffalo Creek shows the folly of attempting to eliminate one of nature's elemental forces, and the importance of thinning out America's overgrown forests.

From its very early days at the dawn of the 20th century, the US Forest Service, the main federal wildfire-fighting agency, embraced the idea of fire suppression: preventing or immediately extinguishing all wildfires.

Inside Pike National Forest near Denver

The concept was not without its critics, but suppression became the dominant approach after the Big Blowup of 1910, external when hundreds of fires ravaged three million acres of Washington, Idaho and Montana in just two days, killing more than 85 people and leaving entire towns in ruins.

From that moment on, the Forest Service went to war with wildfires on federal land.

In 1935, the service introduced a "10am policy". The goal was to extinguish every fire by mid-morning on the day after it was reported.

This meant forcing ranchers and other stewards of the land to stop the practice of carrying out controlled burns, something Native Americans - and nature - had been using for centuries to manage the environment.

In the 1960s and 1970s, some scientists began to argue that fire suppression was causing more harm than good, stressing the crucial role fire plays in forest ecosystems.

But to this day the desire to allow certain fires to burn is tempered by the importance of preserving human life and settlements in the now rather-less-wild lands of the west.

"Today we have 44 million homes that are close to our national forest," points out Tom Tidwell, chief of the US Forest Service, which today manages 154 national forests and 20 grasslands across 44 states and Puerto Rico.

This human encroachment into the wilderness "has significantly reduced our ability to manage fire" he says.

A century of fire suppression has allowed the forests to become more dense and more combustible. Add the combined effect of drought and bark beetles that have left an estimated 66 million dead trees, external in the southern Sierra Nevada alone, and the burn is long from over.

"The number of megafires that we're seeing, that is the new norm," warns Mr Tidwell, who has previously described the policy of fire exclusion and suppression, external as "disastrous".

Still, the chief proudly points out that his teams manage to snuff out 98% of wildfires, which they decide to tackle at an early stage.

Doing so is not cheap. The Forest Service reports the proportion of its budget dedicated to firefighting has risen dramatically from 13% in 1991, to 56% today.

This in turn means federal foresters have far fewer resources to invest in thinning out forests and preventing devastating fires in the first place.

Of course the problem does not just extend to federal land. States, rural communities and individual home owners pay a heavy price, too.

Due north of Pikes Peak, 8700ft (2652m) above sea level, Nancy Zorensky looks out from her ranch on a view which would have a real estate agent in palpitations. It is a wild, isolated and beguiling place.

"When we first moved in, we looked out over that and thought, 'This is the most beautiful carpet of trees,'" says Ms Zorensky.

But all was not well in paradise. There are now no fewer than five big burn scars to be seen from her home, including a streak of pale green which marks the path of the Buffalo Creek wildfire.

The Zorenskys watched the wildfires race towards their property with terror. They had several uncomfortably close calls.

"We started seeing these fires and something was wrong. These crown fires just ate up the landscape very quickly."

With help from the American Forest Foundation, Ms Zorensky and her husband began to investigate what was going on. It turned out that the thick forest on their doorstep was not as wild and natural as it seemed.

Before the West was settled, say foresters, this area was made up of meadows and clusters of trees, with greater biodiversity and a preponderance of fire-resistant Ponderosa pine trees, rather than tightly packed, and in many cases dead or dying, Douglas Firs.

And so the Zorenskys set loggers to work restoring some 230 acres around their property to its previous state, better able to withstand fire and also, they hope, to make it healthier and more sustainable.

Nancy Zorensky on her land

Such treatment is expensive but the costs, say its advocates, are a fraction of dealing with the fall-out of megafires laying waste to the land, claiming lives and property, and turning forests into prairie.

The US Forest Service has also been using logging to thin out the forests. Chief Tidwell says between 2009 and 2015, the Forest Service treated around 12 million acres - all close to communities in order reduce the hazard of wildfire.

However, the agency is hampered by the budgetary squeeze and the pressure to keep fighting fires. Mr Tidwell reckons another 50 million acres is in urgent need of treatment.

He is calling for a radical rethink of funding for megafires, arguing that they should be treated like other natural disasters such as hurricanes, volcanoes or floods.

The "worst case scenario", he says, would be to "continue the status quo".

Doing so would mean continuing to lose homes and "as hard as it is for me to say", continuing to lose firefighters.

Mr Fry would agree with that sentiment. He argues that people need to allow fire to do its natural job of managing the environment.

"No one ever lost their job for fighting a fire as a fire manager or a policy maker," he says. "The far more difficult decision is to allow a fire to burn."

But he has a word of caution about the dangers of doing nothing.

"Mother Nature," he says, "bats last."