New York bombing: What next in the investigation?

- Published

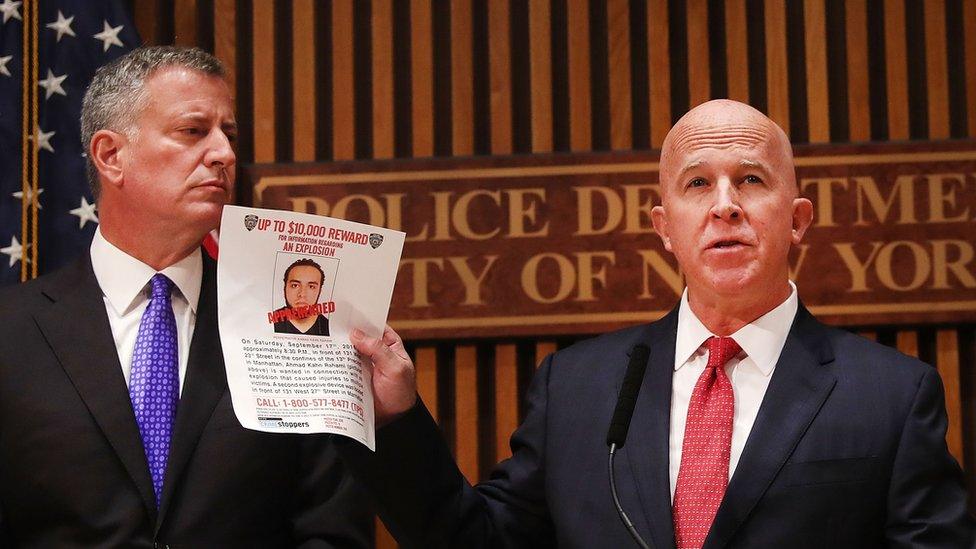

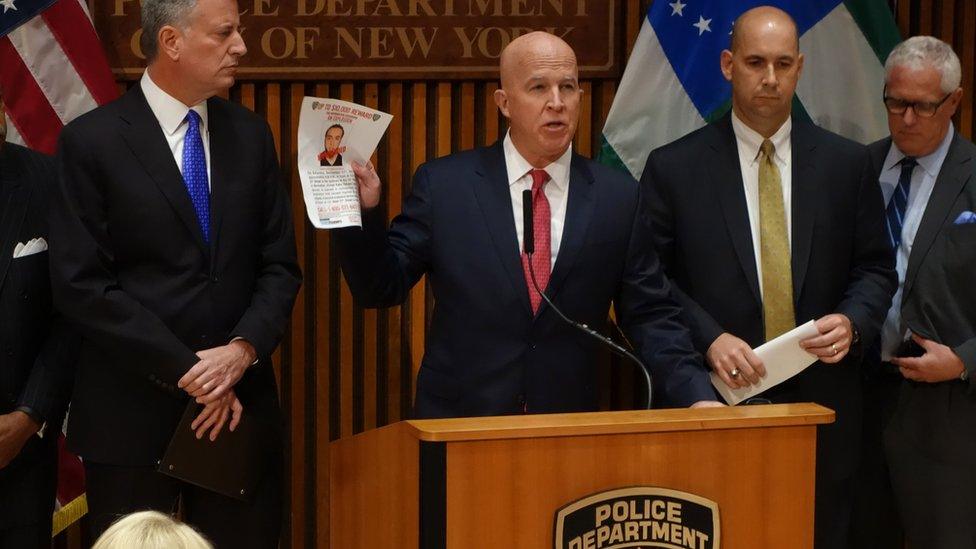

NYC Mayor Bill De Blasio and Police Commissioner James O'Neill appealed for help in finding Mr Rahami

The man suspected of planting bombs in New York and New Jersey, Ahmad Khan Rahami, has been taken into custody. So what happens next?

Fifteen years after the al-Qaeda attacks on the US, New York and other cities are fortified with armed guards, surveillance cameras and barricades. Setting off a bomb - and terrorising people - is harder than it used to be.

A device exploded in a Dumpster on Saturday night in Chelsea, sending shrapnel into the air and injuring 29 people. It could have been worse.

"This was a failed attack," said Fordham Law's Karen Greenberg, the author of Rogue Justice: The Making of the Security State.

Other attacks have killed dozens, even thousands. In the wake of these atrocities, federal agencies were created to protect the homeland - and new laws were written to give officials more authority to prevent terrorism.

Police officers, shown where Rahami was arrested in New Jersey, look for evidence

The impact of the Chelsea bombing was muted. Rather than mayhem and chaos in the wake of the explosion, New Yorkers saw a well-organised manhunt.

First law enforcement officials said Rahami may have been responsible for the Chelsea bombing. They also said he appeared to be linked to explosives found at West 27th Street and in Elizabeth, New Jersey.

After a burst of gunfire, he was taken by police. He was brought to a hospital so he could be treated for a gunshot wound, and he's been charged with the attempted murder of police. But building a case on the terror allegations will take longer.

He'll be questioned as soon as possible, says Jeffrey Ringel, a former Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent who's now director of a security consultancy, the Soufan Group. The agents will have to wait until he's no longer under sedation, though, or they won't be able to use his statements in court.

Afterwards he's likely to be held in the Metropolitan Correctional Center, which is located on Pearl Street in lower Manhattan. Then he'll be put on trial if they have enough evidence.

Rahami's photo, shown by Police Commissioner James O'Neill, says he was apprehended

Law enforcement officials are now trying - in a cool, methodical manner - to build a case against him. They're working together on a joint terrorism task force, which was designed to help them prevent future terrorist attacks and to track down suspects who've crossed borders.

A "force multiplier", as Ringel describes it, the joint terrorism task force has offices in New York City and Newark, New Jersey. These officers are now trying to collect biometric evidence, such as fingerprints and DNA, from the site of the explosion in Chelsea.

The bombs themselves are being analysed. One was made of a cooking utensil and a mobile phone.

Spike Bowman, who used to head up the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)'s national security law unit, said investigators will also look at Rahami's phone, doing "link analysis", to see who he's friends with.

Mr Rahami is originally from Afghanistan. Officers in New York will speak to those who are stationed in Kabul, trying to see if there are connections between him and international groups.

Gov Andrew Cuomo said during a CNN interview on Monday that he thought the attacker - or attackers - might be linked to an international militant group.

That may be true. But so far no-one overseas has claimed responsibility for the attacks.

In this way the case of the Chelsea bombing underscores the way militant leaders operate today - compared to how al-Qaeda commanders carried out attacks.

The al-Qaeda attacks were choreographed - and catastrophic, with nearly 3,000 people killed in 2001.

It's not clear whether the Chelsea bomber had ties to an international group. But other attackers in the US have claimed allegiance to the Islamic State group (IS).

IS commanders tell followers to carry out their own attacks. They're expected to learn how to build bombs and to choose targets.

"This may not be the JV team," says Greenberg, making a reference to the president's misguided claim a couple of years ago that IS was not a serious problem. "But the ability of Isis to recruit and organise and train is not comparable to al-Qaeda."

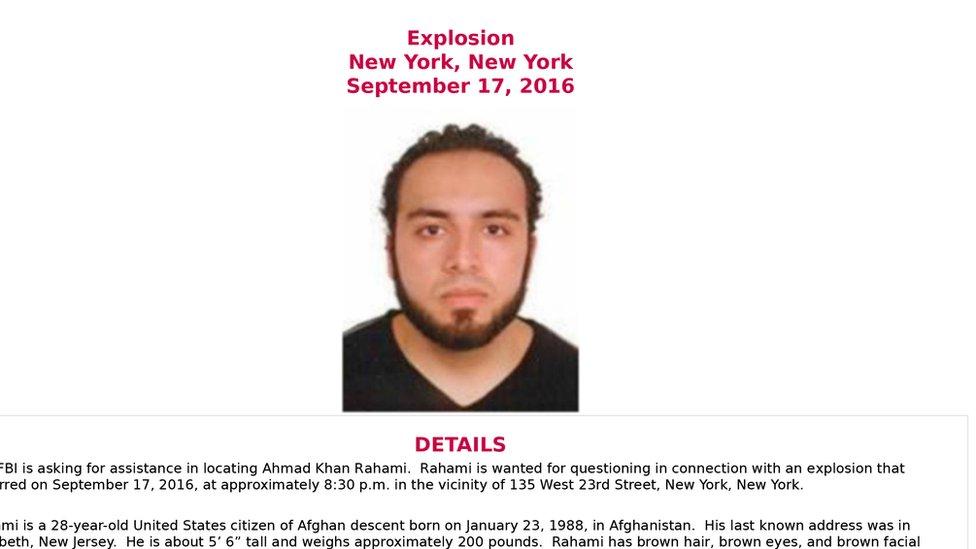

"Armed and dangerous", Ahmad Khan Rahami was taken into police custody

In the Chelsea bombing, the attacker chose West 23 Street as a target. It's hardly an iconic location. It's possible that the attacker knew someone there or had a grudge against the neighbourhood.

There's another possibility: Chelsea may have been chosen because it was easier to get to - and simpler to attack - than a famous monument.

In the past, militants had a wider choice.

One of them, Faisal Shahzad, left explosives in Times Square in 2010. Describing himself as a terrorist, Shahzad tried to set off a bomb there (it fizzled).

Al-Qaeda, of course, went after Wall Street and the Pentagon.

Today places like Times Square, the Statue of Liberty and other well-known sites in New York are carefully guarded. Cameras are mounted here and in other places to reduce crime - and to make things harder for militants.

Even in Chelsea, cameras are posted. That's how law-enforcement officials were able to tell New Yorkers about Rahami.

In the video, he's wearing a jacket and has a bag slung over his shoulder. Law enforcement officials put out an alert, asking people to help find him.

The officials showed excellent tradecraft. Rahami's tradecraft, however, was weak. He was caught within 48 hours. Someone saw him asleep in the doorway of a New Jersey bar.

Follow @Tara_Mckelvey.

- Published19 September 2016

- Published19 September 2016

- Published19 September 2016