UN focuses on refugees - will it be enough?

- Published

A woman walks past hundreds of refugee life jackets collected from the beaches of Chios, Greece, on the edge of the East river in New York to call attention to the refugee crisis

This week the centre of attention for the global refugee crisis shifts from the beaches of Greece, the refugee camps of Jordan, the shoreline of Libya, the fatal waters of the Mediterranean and the battlefields of Syria to the riverside home of the United Nations in New York.

The worst human displacement problem the United Nations has ever confronted will be the focus of two major events here aimed at galvanising worldwide action. As this film shows, the scale of the problem is immense:

Millions of people have been displaced - more than at any time since World War Two

The first event, held on Monday, is a UN refugee and migration summit. The following day Barack Obama will convene his own refugee event on the fringes of the UN general debate, the annual diplomatic jamboree held in New York that draws leaders from all over the world.

At the UN event, world leaders will adopt the New York Declaration, a document enshrining certain principles, such as a commitment to share responsibility for the refugee crisis more equitably between member states and to combat racism and xenophobia.

Despite its grandiose title, however, the "outcome document", external is a classic UN fudge. To secure the backing of UN member states, it has been written in often vague and generalised language and lacks binding, concrete commitments.

Absent from the document, for example, is a clear commitment to resettle 10% of the world's refugees.

A clause on the detention of children was watered down - and one country that pressed for that was the US, which detains undocumented children crossing its southern border from Mexico.

Rather than saying that detention should be prohibited, it reads detention "is seldom, if ever, in the best interest of the child".

More from the BBC

A Syrian refugee sits inside her family's tent on the island of Chios in Greece

At a time when populist politicians like Donald Trump have fuelled anti-immigrant sentiment, western governments have been reluctant to make fresh commitments and to adopt tougher language.

The New York Declaration will launch two years of further negotiations aimed at producing two new compacts, one focused on refugees, the other on migrants. But again, this feels like kicking the can down the road. UN officials have defended the summit, claiming it has the potential to be a "game-changer".

They also point to meaningful language in the New York Declaration on combating exploitation, racism and xenophobia, saving lives en route, and guaranteeing that border procedures adhere to international law.

Even putting down on paper the need for more responsibility-sharing between nations is seen as an advance, given that just ten countries host nearly 60% of the world's refugees.

While welcoming parts of the declaration, NGOS have been critical overall. Oxfam has called it a disappointing outcome.

"World leaders will meet in New York for speeches, dinners and flashy events," says Josephine Liebl from Oxfam's Global Displacement Campaign.

"Sympathy about this global crisis will be voiced, but words need action." Oxfam would like to see rich countries offer more resettlement places, to expand safe and legal routes to protection and support poorer countries financially.

"The declaration agrees to responsibility sharing in theory, but does little to ensure responsibility sharing in practice," says Josephine Liebl.

The United States decided to host its own summit, partly due to frustration that bureaucratic infighting between the UN's various agencies was undercutting the organisation's response.

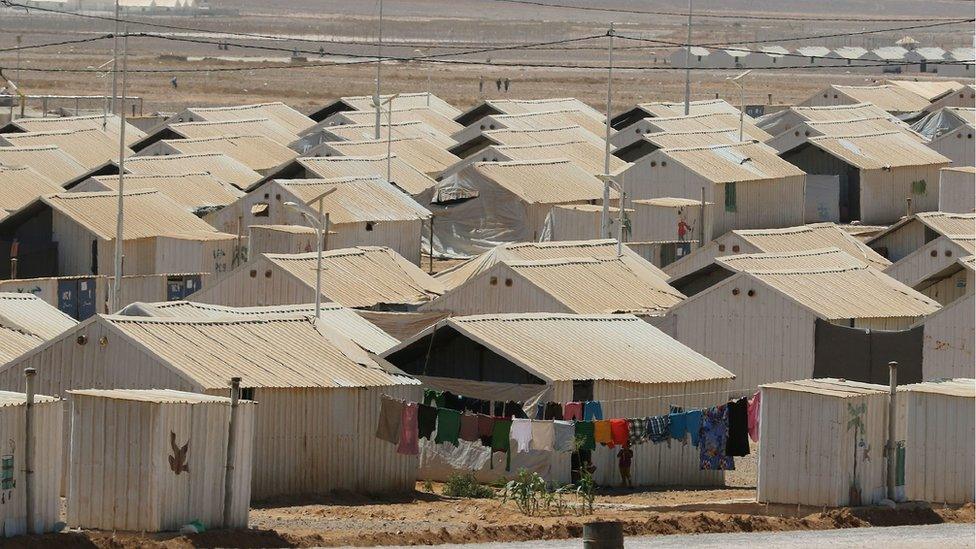

A Syrian refugee camp in Azraq in northern Jordan

Aiming to get more concrete commitments, it has made its own gathering a "pay to play" event. Only countries that have made significant new commitments get a seat at the table.

Broadly the aims are threefold. First, to secure regular contributions from at least ten new nations, and to get a 30% increase in funding for global humanitarian appeals, from $10bn (£7.6bn) in 2015 to $13bn this year.

Second, to urge countries already admitting refugees to double the global number of resettled refugees. Third, to increase the number of refugees in school worldwide to one million.

In practical terms, the Obama summit will be the more significant of the two events. Substantive pledges are sure to come from it. At least 45 countries have paid to play, and US officials are already confident they will reach or exceed their targets. Yet as Josephine Liebl from Oxfam notes: "It's a one-off event with no follow-up mechanism."

The scale of the problem, which has been brought into such heartrending focus by the refugee crisis in Europe, is immense. But the international response has been inadequate. In 2015, the UN refugee agency projected that 960,000 refugees were in need of resettlement, but that only 81,000 people had been resettled.

Some of the world's richest countries have a very poor record of admitting refugees.

Children play in a tent in the "Village All together" in Lesbos

In 2015, Japan admitted just 19. Brazil welcomed thousands of athletes for the recent Rio Olympics, and hundreds of thousands of tourists, but only 6 refugees. As for Vladimir Putin's Russia, it has admitted none at all. The burden is being borne disproportionately by poorer countries. Almost 90% of the world's refugees are hosted in developing countries.

The UN also faces a funding crisis that rich countries have done little to alleviate. The UN aid appeal for Syrian refugees is currently only 49% funded. And that's good compared to the appeal for South Sudan, which stands at 19%, and Yemen, which is only 22% funded.

Human rights groups have also condemned some of the harsh, inhumane policies that countries have adopted towards refugees. Human Rights Watch says its has documented Turkish border guards firing on civilians who appeared to be seeking asylum.

It has accused Pakistan and Iran of coercing Afghanistan refugees to return to their war-torn countries, in violation of international law.

Hungary, which built a barrier on its border with Serbia and Croatia, has used tear gas and water cannons against migrants trying to enter the country.

Australia's offshore detention centre on the remote Pacific island of Nauru frequently comes in for strong criticism. The United States, Italy, Mexico, and Greece also detain asylum seekers.

Ban Ki-moon reflects on time as UN secretary general

"This is not just about more money or greater resettlement numbers," according to Kenneth Roth, the executive director of Human Rights Watch, "but also about shoring up the legal principles for protecting refugees, which are under threat as never before."

New York, this great polyglot city, is a highly symbolic setting for a summit on refugees and migration.

Over the years, it has been the entry point into America for millions fleeing wars and persecution, who have landed on these shores seeking safer and more abundant lives.

In many ways, it is the ultimate city of new beginnings.

The criticism of the New York Declaration is that it will not do enough to alter the status quo.