Police accountability: Why body cam footage is not always released

- Published

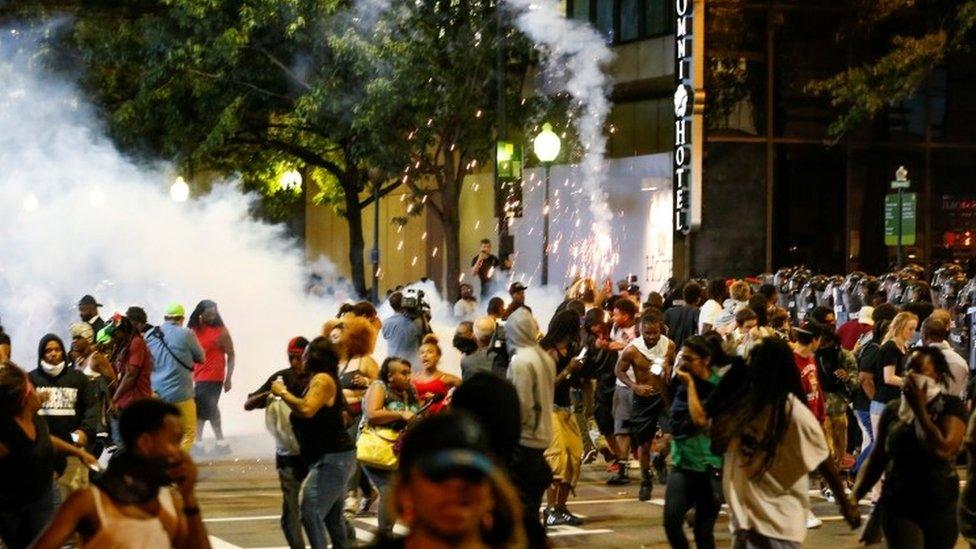

The killing of Keith Lamont Scott on Tuesday has led to violent protests

In North Carolina, a black man is shot by police. According to his daughter, he was unarmed and reading a book. The police say he was armed and refused to drop his gun. Police released bodycam and dashcam footage days after the incident following calls from activists and politicians.

How many US police departments use body cameras?

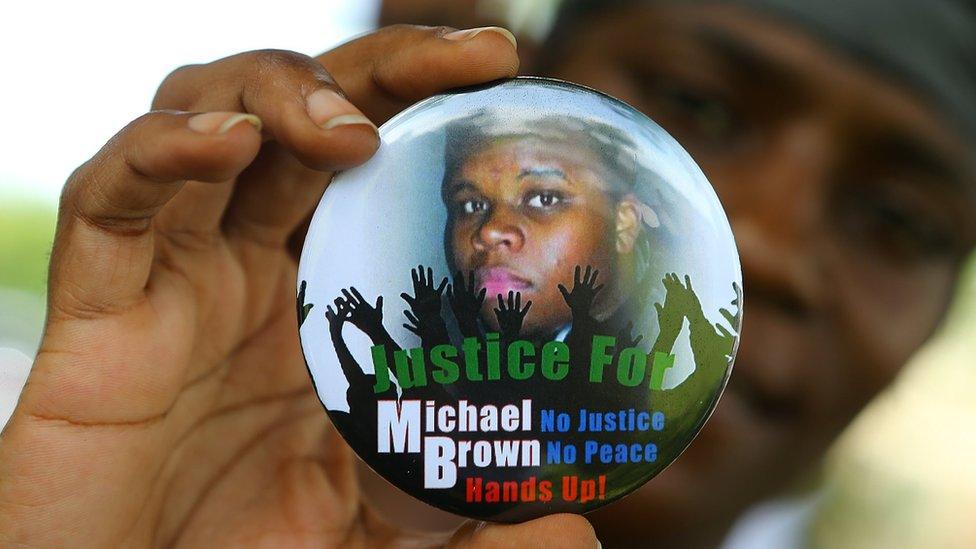

The use of body cameras has grown fast since the police killing of black teenager Michael Brown in 2014

As of August this year, 42 of 68 "major city" police departments in the US have body-worn camera programmes with policies in place, according to the activist group Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. , external

Following the police killing of black teenager Michael Brown and the ensuing riots in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014, the US justice department pledged $20m (£15.4m) of funding in grants for police forces to buy as many as 50,000 cameras across the nation.

The Leadership Conference points out accountability does not automatically follow: "Whether these cameras make police more accountable - or simply intensify police surveillance of communities - depends on how the cameras and footage are used."

So what is the policy, and is it the same across the United States?

Many police departments now have body cams, but the rules on when and how to use them vary hugely across the US

No. At the moment there is no standardised national approach to dealing with the increased volume of police footage.

There is a patchwork of practices across the country, with many police departments failing to have clearly-formulated policies.

For example, not all police forces have a set of rules about when officers must record, whether they need to provide justification for failure to record, and whether individuals filing police misconduct complaints have full access to all footage.

The Leadership Conference have produced a "rate card", external showing how well each department using body cams is doing in a number of civil rights areas, with some coming out better than others.

The police department of Charlotte-Mecklenburg does have a public policy, external, but does not perform well in all areas on the rate card.

Are police obliged to release body cam or dash cam footage?

No.

Although Brentley Vinson, the officer who shot Keith Lamont Scott, was in plain clothes and had no camera on him, three other officers did have theirs on.

Police department policies, where they exist, tend to specify all footage from the body cams are the property of the police department in question, and may not be released without the specific authorisation of the superintendent.

Some states have even passed laws making body cam footage exempt from freedom of information requests.

North Carolina, for example, has a new law restricting release of such footage without a court order, but the law does not come into effect until 1 October.

Why would police not release footage?

For more than a year, Chicago police released no more than a single frame of the dash camera video of Lacquan McDonald's killing by a white police officer

Red tape. Some police departments have strict guidelines on who can view the material, and a decision to release footage may need to pass some bureaucratic hurdles.

It is not conclusive. Different interpretations can be put on something seen from different angles. Even if the evidence shows the victim did have a weapon, police might worry that it provides ammunition for those who do not trust the police. For example, if the camera was switched on half way through the operation, some people might say the police were hiding what happened before the switch.

Legal reasons. Judges may block it because it could prejudice future trials. Or prosecutors could try to prevent it because it could taint a potential jury pool.

There are privacy concerns for bystanders who may have been recorded inadvertently.

It proves the police wrong. Perhaps the police account is not supported by the video evidence, as in the case of Laquan McDonald, a black 17-year-old who was shot 16 times by a white Chicago officer. The police department fought the public release of the footage for more than a year. The officer was charged with murder on the day the footage was released.

The body camera was not switched on at the time. There are many cases where no footage is available. Between September 2015 and May this year, three out of four fatal Charlotte-Mecklenburg police shootings were not recorded, external, according to the Mecklenburg Observer. Across the country, police forces are finding it harder to fund body cams for all officers.

The body camera does not show the incident. Most people remember the killing of Alton Sterling of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in July from mobile phone footage recorded by bystanders. Police footage is unlikely to be released, even after the investigation is completed, because body cameras worn by both officers allegedly "fell off" during the incident.

Why would police release bodycam video?

Milwaukee police was keen to release footage of the death of a black youth in August to prevent rioting, but the Wisconsin Justice Department did not agree

It might stop protests and riots.

In some cases, the police are keen to make the footage public if it shows the officer made the correct decision.

When Sylville K Smith was shot dead by police in Milwaukee on 13 August, the police chief, mayor and state representative called for publication of the police footage.

But the case is under the jurisdiction of the Wisconsin Department of Justice, which said it will not release the footage until after the investigation.

The killing was followed by two nights of protests and rioting.

Police departments can learn, too.

The Chicago police department now has rules which dictate that police must release video footage of a fatal police shooting within 60 days.

It released more than 300 videos of police-related incidents, in an attempt to restore trust between officers and black communities.

It also released nine body cam videos of the fatal shooting of 18-year-old Paul O'Neal in August, just days after the incident.

- Published22 September 2016

- Published14 August 2016

- Published25 November 2015