'Killer clowns' in Canada: Why are these sightings spreading?

- Published

Clown sightings are also become a craze in the UK

After a wave of "creepy" clowns were spotted across the United States late this summer, the phenomenon seems to have migrated north to Canada. Why are these sightings spreading?

"Killer clown" sightings have been investigated by local police in Gatineau, external, Quebec, Halifax, external, Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, external and Bowmanville, Ontario, Toronto, and Ottawa. More reports have spread on Twitter and Facebook.

"I'm having a hard time thinking of anything quite like this phenomenon of evil clowns," says folklorist Prof Timothy Evans.

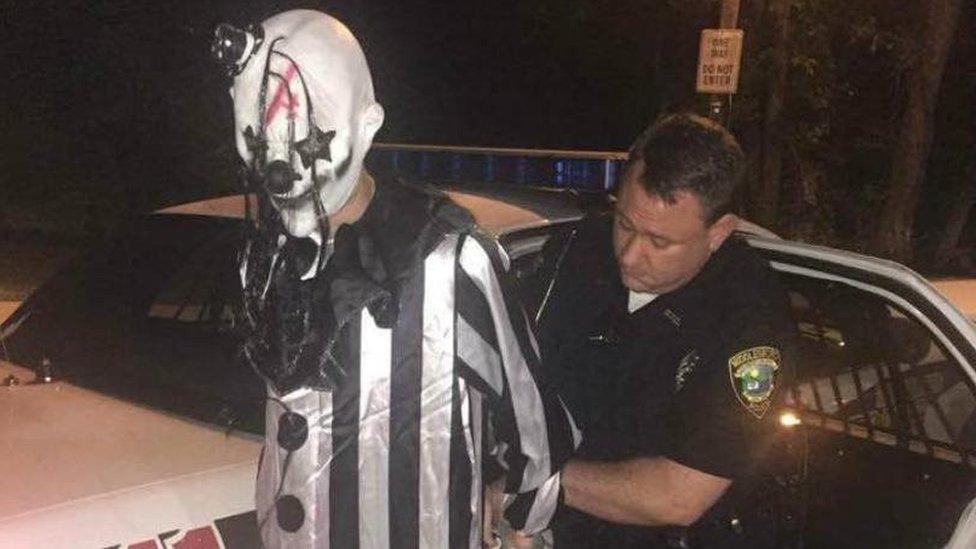

Since late last summer, "killer clowns" have been spotted from Alabama to Nova Scotia. Schools in Texas and Alabama have shut down, and police have made a handful of arrests - both for people making false reports and for people actually dressing up in clown costumes.

The paranoia has even reached the White House, where press secretary Josh Earnest had to field questions about the president's stance on "creepy clowns" during a press briefing on Thursday.

The president has not been briefed on this issue, Earnest said, but "this is a situation that local law enforcement authorities take quite seriously, and they should carefully and thoroughly review perceived threats to the safety of the community, and they should do so prudently".

The clown craze also seems to be spreading to the UK and Australia.

"It's straight out of Hansel and Gretel," says Benjamin Radford, who wrote a book about the clown sighting phenomenon. One of the first waves of clown paranoia that Radford uncovered was in the 1980s, when a number of schoolchildren from Massachusetts claimed a clown was trying to lure them into a van. Police never confirmed their reports.

Indeed, law enforcement officials note a rise of unconfirmed reports and hoaxes involving clown sightings. In Bowmanville, police found nothing suspicious after a Facebook post suggested a "killer clown" was stalking the community.

On Tuesday, Halifax police investigated after a picture of a clown standing near a high school was posted on Instagram. No clown was found near the area, says Halifax Regional Police spokesperson Wendy Mansfield, but the department has received at least 10 reports on social media that "creepy clowns" might be in the area.

No one has actually seen a clown in person, Mansfield says.

But some sightings do involve real people dressing as clowns in order frighten others.

This summer in Gatineau, Quebec, two teens were caught skulking around a playground wearing clown costumes in order to scare children. In Green Bay, Wisconsin, a local actor drew almost 12,000 "likes" on Facebook after he posed around town in a clown costume as part of a viral marketing stunt.

It's what folklorists like Prof Evans call "ostension," or the acting-out of urban legends.

A classic case of ostension might involve a group of high school students going to a cemetery they believe is haunted and "seeing" a ghost. But sometimes it can turn much darker, such as when two young girls in Wisconsin stabbed their friend in 2014 to appease "Slenderman," an internet meme turned folktale created by the artist Eric Knudsen.

Evans says Slenderman is the closest relative to these "creepy clowns."

While most urban legends - such as the classic tale of the "hook man" who preys on unsuspecting lovers parked in remote woods - have been around for decades and were passed down from person to person, Slenderman and "killer clowns" were born relatively recently and spread like lightning online, Evans says.

Radford traced the phenomenon of these "stalker clowns" to 2013, when a young filmmaker from Northampton, UK started dressing up as a clown and posting photos on Facebook as a viral social media experiment.

"They're just basically sort of doing a combination of prank and performance art," he said.

Soon, copycats spread across Britain, Ireland, France and the US. In 2014, French police arrested 14 teenagers who terrorized local residents by dressing as clowns and carrying weapons.

In Staten Island, New York, the clown turned out to be an elaborate marketing ploy for a local production company.

Clowns occupy a powerful place in our pop psyche, Radford said, as a symbol for both the terrors and joys of childhood.

"People love to have two sides of the coin, the things that make us laugh and the things that make us scream," he said.

Unlike classic urban legends, which tend to stick around for decades and are retold consistently over time, Evans says internet myths like "killer clowns" or Slenderman have a tendency to come in waves and then burn out.

Both Radford and Evans said sighting sprees, like the one we're having now, will likely peter out after Halloween.

But Radford, who's studied waves of sightings in 2013, 2014 and 2015, doubts they're ever gone for good.

"I guarantee you that within five or six years there will be another clown scare like this," he said.

- Published23 September 2016

- Published14 September 2016