What can Trump learn from a wrestler and an action hero?

- Published

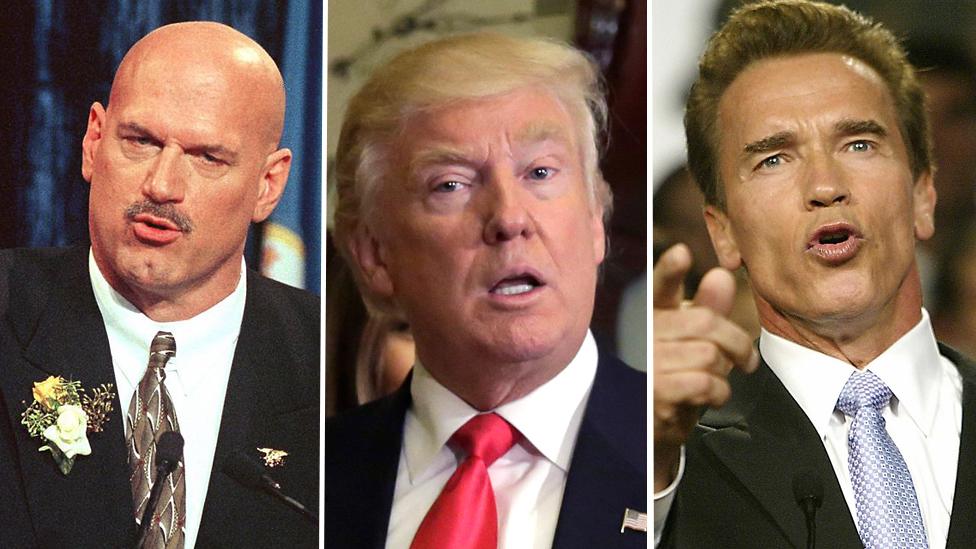

Jesse Ventura (left), Donald Trump and Arnold Schwarzenegger

In January Donald Trump will become the first person sworn in as US president without prior experience in elective office or at the highest levels of the military. While his accomplishment is unprecedented, two modern governors who used their fame as a springboard to public office could serve as guides - and cautionary tales.

Dean Barkley remembers what professional-wrestler-turned-politician Jesse Ventura said moments after learning that he had won his upstart independent bid to be governor of Minnesota in 1998.

"Now what the hell do we do?"

Barkley, who served as the Ventura campaign chair, says he was equally flummoxed. At one point during the evening, he went looking for the briefing books put together by the current governor's office that laid out the post-election transition process.

They were buried, unread, in the trunk of his car.

Mr Ventura's victory was the culmination of an improbable campaign, where the man who goes by the nickname "the Body" prevailed despite being vastly outspent by his Democratic and Republican rivals.

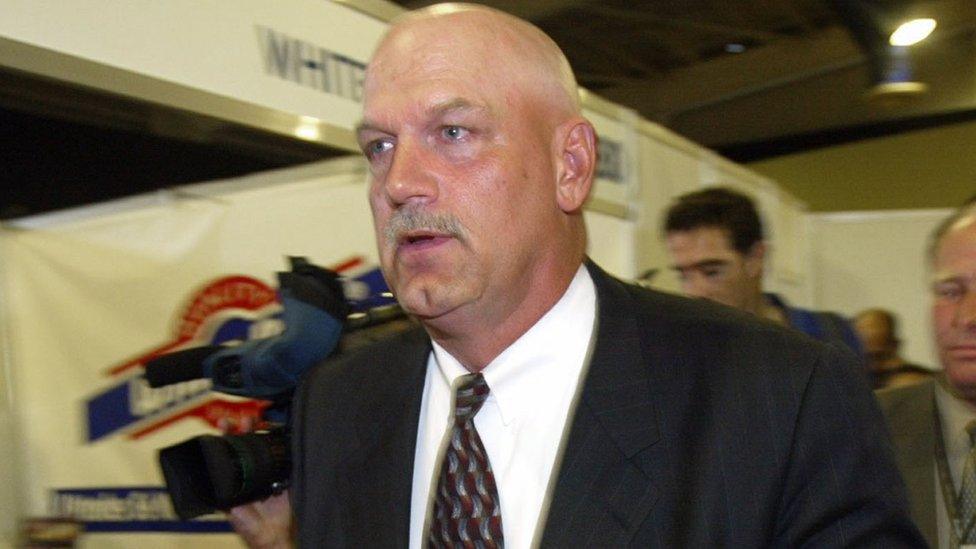

Dean Barkley chaired Jesse Ventura's campaign - and the governor would later appoint him to an open US Senate seat

He ran as the straight-talking outsider, gaining national attention with a memorable television advertising campaign, external featuring Mr Ventura as a children's action figure fighting lobbyists and corrupt politicians.

When he first launched his bid, Mr Ventura was laughed off as a joke. As election day approached, few gave the outsider, anti-establishment candidate any chance of winning. And on election night, even Ventura's own staff was caught flat-footed, unprepared to face a reality that voters had handed their man the reins of power.

"It dawned on me that absolutely no-one knew what to do beginning the next day," says Bill Hillsman, the media consultant who came up with the action-figure advert.

Although he wasn't a governing expert, at 3 am on election night Hillsman found himself alone in a Denny's diner with a sheet of legal paper, making a list of all the things he could think of that the nascent Ventura administration had to do when the sun came up.

And when daylight broke, the phone started ringing off the hook.

"It was a lot of unions, a number of trade groups, people who had business with the government," Hillsman said. "Nobody knew how to go about getting hold of the governor-elect. We were the only connection they could figure out."

In other words, it was situation not unlike the one that reportedly unfolded in Trump campaign headquarters two weeks ago, as aides and advisors scrambled to bring order from the chaos of an improbable victory.

"For the first week or two it was pretty chaotic, just trying to get our feet on the ground of what to do because we didn't have any political insiders to guide us," Barkley says.

He and former congressman Tim Penny hired a team of human resources experts to screen resumes for government positions, then forwarded the top four to Mr Ventura for consideration. They issued a ban on lobbyist involvement and, per the governor-elect's instructions, made selections based on qualifications and not party affiliation.

It's the same advice Barkley says he would give Mr Trump, who he says "pulled off a miracle" by winning the presidency.

"Trust your instincts," he says. "They got you where you are. Don't get side-tracked by political insiders who basically just want you to do their bidding. Pick the best and the brightest regardless of whether they supported you or didn't support you."

So far, that hasn't seemed to be the strategy Mr Trump is following, as he has opted to tap faithful advisors Jeff Sessions for attorney general and Michael Flynn for national security advisor. If he's going to pursue the Ventura model, he'll have to cast a wider net.

According to Hillsman, Mr Ventura's status as a political independent was an advantage that Mr Trump, who often campaigned with little help from members of his own party, should be maximising.

"If you don't owe anybody, you can absolutely pick the best people for the job," he says.

Jesse Ventura's fortunes turned in the last two years of his governorship

The Ventura administration's goal was to strike a non-ideological balance between the Democratic and Republican parties in the state, Barkley says - and for the first two years of his four-year term, it seemed to work. Mr Ventura had campaigned as a no-nonsense outsider, and he was able to win legislative support for a sales tax rebate, property tax reform and increased funding for mass transit programmes and public schools.

The second half of his term, however, was typified by Mr Ventura's recurring feuds with the media and political dysfunction in the legislature, as an economic downturn led to budget deficits. He moved out of the governor's mansion to live in his private house. He drew sharp criticism for the kind of unscripted remark that had been shrugged off during his campaign and the heady early days of his administration but served as a lightning rod when his fortunes turned south.

Mr Ventura announced he would not run for re-election, which Barkley - who had taken a high-level job in the administration - said made Democrats and Republicans solely focused on the race to replace him.

"No one wanted to give him credit anymore for anything," he said. "The whole mindset changed, and it was basically a nightmare - nothing got done."

As Mr Ventura's political star was setting in Minnesota, in California another unconventional politician was about make his move.

Blockbuster action-film star Arnold Schwarzenegger had always entertained the idea of a political career, but it took a strange confluence of events - the recall election of the unpopular Democratic Governor Gray Davis - to elevate him to the California governorship in 2003.

Arnold Schwarzenegger drew legions of fans to his political rallies that celebrated his unconventional campaign

Like Mr Ventura before him (and Mr Trump years later), Mr Schwarzenegger campaigned as the renegade outsider who would clean up a corrupt political system. He travelled around the state with a broom and took the stage at his rallies to Twisted Sister rock anthem We're Not Going to Take It (a song Mr Trump adopted in 2015 until the band leader asked him to stop playing it).

"Arnold Schwarzenegger drew huge crowds around the state due in large part to his celebrity, along with the frustration people had with government and the status quo," says former Congressman David Dreier, who co-chaired the Schwarzenegger campaign and served as the head of his transition team.

Mr Dreier adds that Schwarzenegger rallies had much of the same drama and excitement that characterised Mr Trump's presidential campaign. For instance, during one rally, the actor-turned-candidate dropped a wrecking ball on an old car to demonstrate his opposition to a car tax imposed by the current governor.

"Arnold Schwarzenegger in many ways blazed the way for Donald Trump," he says.

Mr Dreier says Mr Schwarzenegger and his wife, Maria Shriver, asked him to head the governor-elect transition team at a Starbucks coffee shop about a week before election day. They told him they wanted someone with government experience - but without ties to the state capital in Sacramento.

"I could count probably on two hands the number of times I've been to Sacramento," Mr Dreier says.

Mr Dreier, who is now advising the Trump transition team, says the most important thing an outsider candidate can do during his transition is to use it to set the administration's priorities and bring in veteran political hands - something that Mr Trump did when he hired Republican Party Chair Reince Priebus to be his chief of staff.

"What do you want to accomplish?" he says. "That's what Donald Trump needs to be thinking about."

Upon assuming the governorship, Schwarzenegger faced his own steep political learning curve, as he struggled against an uncooperative state legislature and grappled with reconciling the grand promises he made on the campaign trail. He tried to circumvent the state legislature by offering ballot measures Californians could directly vote on, but all his proposals were defeated.

"Being a political novice meant he didn't understand how difficult some of these things would be and what the limits of the power of the governor are," says Terry Christensen, a political science professor at San Jose State University who co-wrote a book about the Schwarzenegger governorship.

"As an outsider he had a different perspective, and maybe it opened him to ideas that insiders wouldn't entertain, but you still have the challenge of bringing those ideas to fruition," he adds.

Mr Schwarzenegger had his share of legislative accomplishments, such as co-operating with the Democrats to pass more stringent environmental regulations. Like Mr Ventura, however, the final days of his administration were typified by frustration, large budget deficits and sinking popularity, as the political powers that be reasserted control.

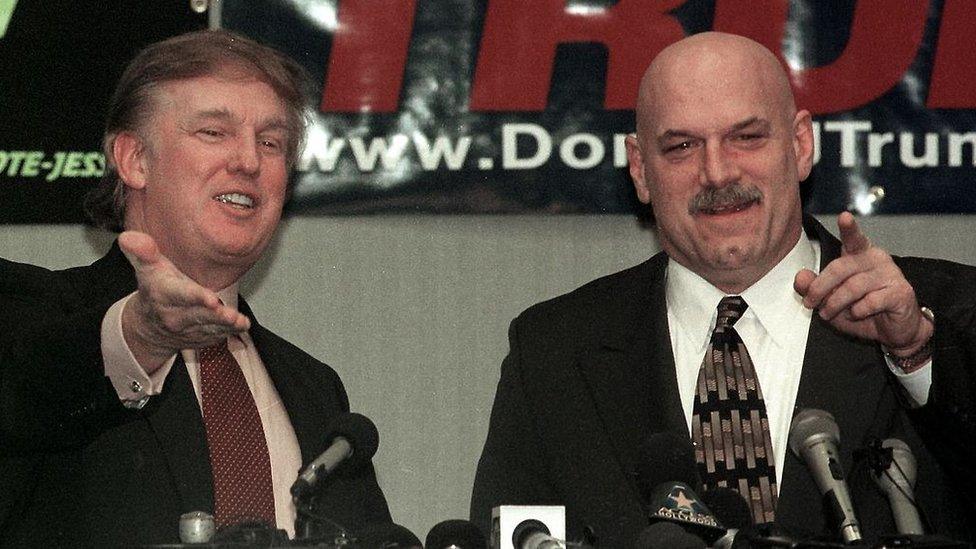

In 2000, Donald Trump sought out Jesse Ventura for advice on running an outsider campaign

"These past seven years," wrote, external LA Magazine's Ed Leibowitz in 2011, "we Californians have experienced an Arnold Schwarzenegger many of us wish we'd never met: a politician who often seemed in over his head, who prevaricated and bungled, switching sides as it suited him to save his political skin."

The lustre of the outsider delivered powerful public office to Mr Schwarzenegger, as it did Mr Ventura, but the grind of governing eventually brought both men down to political bedrock.

Back in 2000, when Mr Ventura was still near the height of his popularity, Mr Trump - then contemplating a third-party bid for the presidency - travelled to Minnesota to meet with the team that helped secure the governorship for a man who had made his name taunting opponents in the wrestling ring.

According to Barkley, the New York real estate mogul was an attentive listener.

"He's not stupid," Barkley said. "He came to find out how the hell we did it here. And he followed our blueprint pretty well."

It's a blueprint that will put Mr Trump in the White House. It's not quite as clear about what he should do once he gets there.