Arctic hamlet takes land battle to Canada's highest court

- Published

Clyde River residents hold up anti-seismic blasting signs on the bow of the Arctic Sunrise, during a ship tour

A tiny Inuit community battling to protect their land from oil and gas testing is taking its case to Canada's Supreme Court on Wednesday.

The people of Clyde River, Nunavut, say they were not consulted about the use of seismic testing to probe for reserves under the ocean.

Their campaign has been backed by celebrities Leonardo DiCaprio, Emma Thompson and Oprah Winfrey.

The Supreme Court, external hearing comes after nearly two years of failed appeals.

The community's legal battle has led to an unusual alliance with Greenpeace, which once opposed the Inuit on seal hunting. The campaign group is helping to pay for their legal fees.

If the court rules in their favour, it could mean that indigenous communities would have greater sway on projects affecting their land in the future, although there may not be a verdict for some time.

A day in court

In 2014, the National Energy Board approved a five-year project to test for oil and gas reserves under the ocean around Baffin Island, where Clyde River is located.

With a population under 1,000, the tiny hamlet relies heavily on hunting and fishing for both food and trade, and is afraid that seismic testing, which uses loud noises, will affect the migratory patterns of animals.

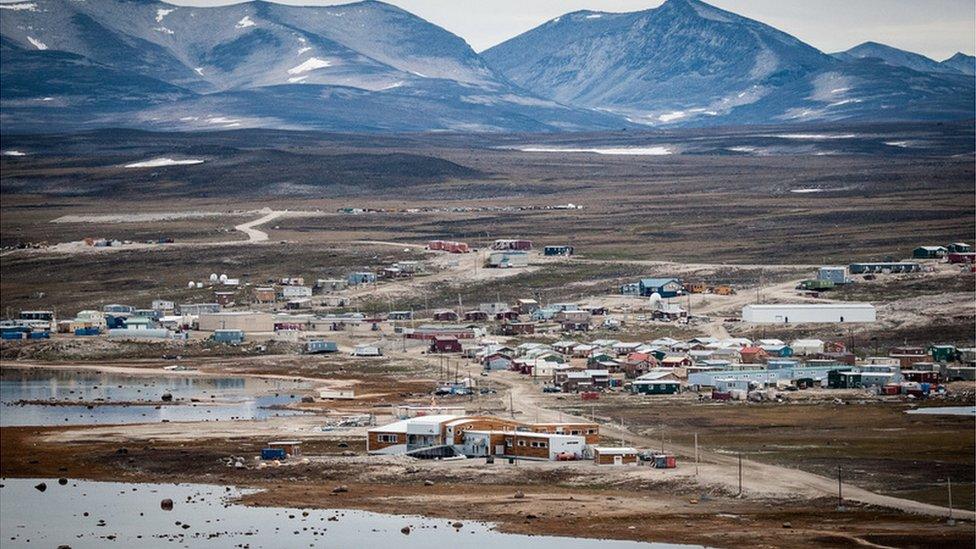

Clyde River, Nunavut is located on the shore of Baffin Island, and home to about 1,000 Inuit.

The people of Clyde River say the government simply informed them of their plan, rather than carrying out a consultation.

According to the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement that created the territory of Nunavut, Inuit have a right to hunt and fish for wildlife on the land, as well as a right to consultation.

"We want to be full partners, we want to say yes or say no, and also to have an input as to when and where," Clyde River's former mayor Jerry Natanine told the BBC.

But in August 2015, a judge for the Federal Court of Appeal ruled that the government fulfilled its duty to consultation with the Inuit, external, and that the they did not need to get the community to agree with the plan.

Celebrity cause

The Arctic community may be isolated from the rest of the world, but the residents of Clyde River have had to learn the ins and out of social media activism to bring their message to the world.

Using the slogan ''we do not consent'' and the hashtag #NoiseComplaint to get their point across, the Greenpeace campaign has attracted the support of celebrities such as Winfrey, Thompson, DiCaprio and Jane Fonda, and online petition has collected more than 100,000 signatures.

Thompson even travelled to Clyde River with her daughter to make a film about the community this summer, which she presented at a United Nations conference on oceans and the law of the sea.

''There are no more natural ocean sanctuaries, and it's up to us to create them,'' she pleads in the video from the shore in Clyde River. , external

Clyde River's alliance with Greenpeace is far from ordinary. After opposing the seal hunt for decades, many Inuit held Greenpeace responsible for the plummeting value of seal skins, external, an important industry for the community.

"When I grew up I hated Greenpeace," Mr Natanine said.

Inuit traditionally hunted for seal on Baffin Island, but anti-seal hunt campaigns decimated the industry.

But in 2014, Mr Natanine read an apology from Greenpeace Canada, external who said the environmental organization regrets the harm their anti-seal hunt campaigns caused the community and will support indigenous peoples' land rights in the future.

Mr Natanine said the apology made him approach his father, a former seal hunter who lost his livelihood when the price of seal pelts plummeted, to ask what he thought about working with the organization on the Clyde River appeal.

"If you can use them, if they can help you to stop this thing, we have to do everything we can to stop it," his father told him.

Greenpeace's Farrah Khan said working with the community has helped the organization begin to "make amends" for past mistakes.

"We want to show through our actions that this is a different organization," she told the BBC.

- Published12 January 2016

- Published18 October 2013