Mexicans rethink relationship with US

- Published

Foreign officials in Washington are struggling to get to know the president-elect's transition team and are experiencing a sense of anxiety about the incoming administration.

But none of them, as an Obama White House official told me, are as worried as the Mexicans.

Recently, a New York City panel on Mexican infrastructure, featuring Gerardo Ruiz Esparza, Mexico's secretary of communications and transportation, and other officials from Mexico City was abruptly cancelled.

The panel had been planned long before the election, when most anticipated a very different outcome.

"This is quite a tense moment," said Shannon O'Neil, a Mexico expert at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. "It's very hard to go out and talk about infrastructure."

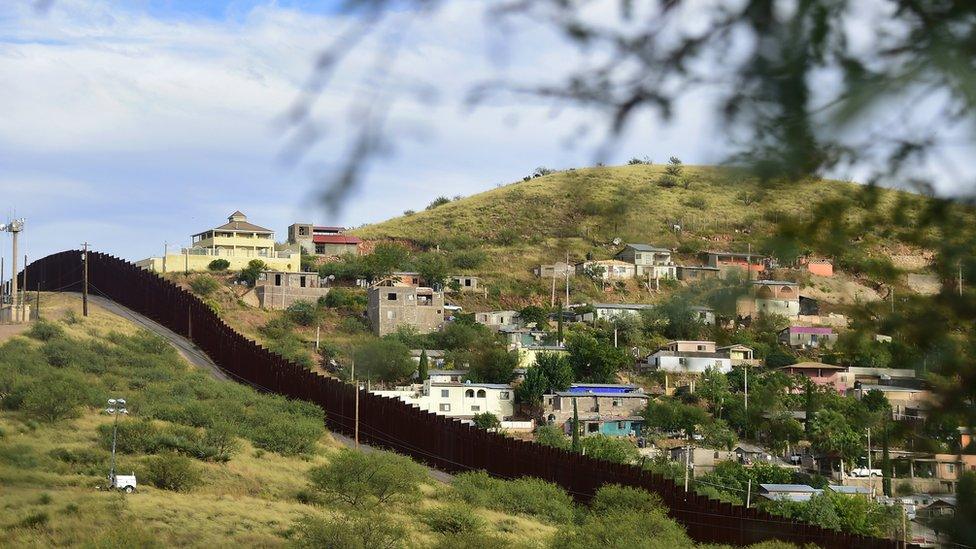

The president-elect's wall would stretch across the border, including parts of Arizona

Cabinet members in Mexico City sent a letter to Foreign Affairs, which was hosting the conference at the Council on Foreign Relations, and said they were cancelling because of "unforeseen circumstances", a Mexican official told me.

The Mexican officials didn't say anything in their letter about the election of Donald Trump. But his victory played into their decision to call off the event.

Michael Camunez, a former Obama White House official who was planning to speak at the event, said he understood the reasons. "It's a time of uncertainty," he said.

In international relations, there's almost nothing worse than uncertainty, as the people of Taiwan and China know. They've been wondering over the past several days about President-elect Trump's decision to speak on the phone with the Taiwanese leader - and what this means for US policy.

It was the latest in a series of ambiguous signals that have been a hallmark of Mr Trump and his team. This has created profound uneasiness for diplomats.

In both a pragmatic and a philosophical sense, Mexican officials are wondering about infrastructure. "What kind of North America are we going to see in the next three months?" the official said, talking about the conference and their future. "Who knows?"

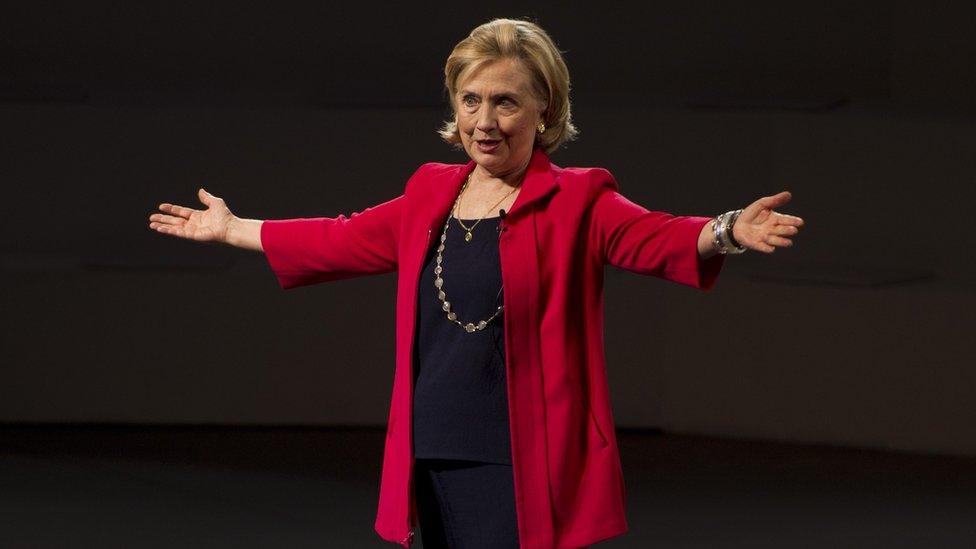

Hillary Clinton ,shown in Mexico City in 2014, was expected to win the election

The event was set up with the implicit understanding that the Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton, a frontrunner in the polls, would be the next president.

She'd already served as secretary of state, and her views about foreign policy were widely known.

The officials may not have agreed with everything she said, but they knew what to expect from her.

Mr Trump is different. A businessman, he's never served in public office.

His view of Mexico contrasts sharply with those held by previous presidents. During the campaign, he called Mexicans "rapists" and criminals. He said he'd deport millions of them.

He's also spoken in a negative way about the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta), which provides the infrastructure for industries spread across the US, Canada and Mexico.

The people of Mexico have built their economy on the trade agreement, and they rely on the US for about one third of their income. Last year they sent goods and services worth approximately $316bn to the US, and the importance of their relationship to the US - in both commercial and personal terms - is woven into the fabric of their nation.

More than 11 million people who are originally from Mexico now live in the US.

Ties between the two governments became especially close after the 2001 terrorist attacks. Security officials deepened their relationship as they tried to combat militant groups and drug trafficking.

The president-elect visited Carrier, which will keep factories in the US

The election of Mr Trump means that the relationship between the US and Mexico is likely to change.

He said he'd build a wall - and that Mexicans would pay for it. The wall would stretch across the 2,000-mile border, making it the biggest infrastructure project since the construction of the US highway system in the 1950s and 1960s.

Mexico's president, Enrique Pena Nieto, compared, external Mr Trump's rhetoric to the kind that was used by Mussolini - and said Mexicans would not fund the wall.

Now the two leaders will have to work out an understanding. They'll meet shortly before the US presidential inauguration on 20 January, according to experts who are close to the Mexican officials.

Until then the Mexican officials are watching the situation closely.

"They've moved beyond the panic stage," said Duncan Wood, director of the Mexico Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington. "They're now in the evaluation stage."

Mexico's president, Enrique Peña Nieto, compared Trump to Mussolini

Since the election, the situation has changed - and so have some of Mr Trump's views. He said in a television interview that the wall wouldn't have to cover the entire border: some sections could have a fence.

On Thursday he announced that a company, Carrier, would keep its Indianapolis factory open, saving 1,100 US jobs, instead of moving work to Mexico, as its executives had once planned.

It was a victory for Mr Trump, who'd campaigned on a promise to help American workers and save jobs.

"It gives Trump an early win," said Camunez. This could mean that he'll decide to soften his positions on trade and Nafta - and will become less savage in his attacks.

Analysts at conservative think tanks in Washington believe that in principle he'll stand by his claim that the trade agreement is flawed, however, and that it must be changed.

As the American Enterprise Institute's James Pethokoukis said: "I don't think this is going to go away."

In the meantime officials from the foreign ministry, treasury and other government departments in Mexico City are travelling to the US and speaking with people about diplomacy, immigration and other matters that are crucial to their relationship.

The Mexican official who told me about the conference - and its cancellation - said they're trying to work out issues as best they can.

But they're also preparing for change - and surprises - in the coming months as the Trump administration takes office.

"We are in for a rough time, but that doesn't mean you stop doing everything," the Mexican official said. "On some issues it will be business as usual. On others - we'll have to wait and see."

Follow @Tara_Mckelvey

- Published10 November 2016

- Published1 September 2016

- Published1 September 2016