Presidential phone calls: How do world leaders talk to each other?

- Published

Donald Trump taking a call on his private plane in 2000

US President-elect Donald Trump has been making headlines with his unconventional approach to diplomatic phone calls.

According to the New York Times, US foreign allies "were blindly dialling in to Trump Tower" in the days after the national election.

Further upset was caused when Mr Trump announced he had spoken directly to the Taiwanese president, Tsai Ing-wen, even though formal relations between the US and Taiwan were cut almost 40 years ago at China's behest.

But what is normal procedure for conversations between world leaders? Here are some of the steps taken to smooth out the process and avoid potential pitfalls, from linguistic misunderstandings to prank callers.

Hi, it's Putin, is Obama in?

US President Barack Obama on the phone in the Oval Office of the White House

"Hello, can I speak to the president?" is not an off-the-cuff request an operator is ever likely to hear from a world leader.

By the time the initial pleasantries are exchanged between heads of state, the groundwork will have been done behind the scenes by the leaders' respective staff.

"When there is an established relationship between two countries, it might be as simple as one situation room calling its counterpoint and saying my head of state wants to speak to yours," says Stephen Yates, who worked as deputy national security adviser to former US Vice-President Dick Cheney.

When countries are in less frequent contact, an ambassador may make the first formal request on their leader's behalf. They will set out the proposed agenda and reasons for the call and, if agreed, the reciprocal team would then work it into busy schedules.

A helping hand for big issues and small talk

World leaders are typically well briefed before speaking to each other.

In the US, the president is given a dossier from the National Security Council (NSC), the principal US advisory body on national security and foreign policy.

If it is a simple courtesy call, the information provided may be basic, including details on who initiated contact, and two or three recommended talking points. There may also be some need-to-know personal information, such as a reminder to ask after a sick husband or wife.

If the topic is sensitive, the NSC will offer the president an additional short briefing, and then listen in on the call.

Are we alone now?

Russian President Vladimir Putin and German Chancellor Angela Merkel both speak each other's language but may prefer to use their mother tongue on the phone

World leaders usually have various people listening in on their conversations, including aides and interpreters.

Even when leaders speak another language fluently, they often choose to conduct official calls in their mother tongue.

"Sometimes that is down to national pride, but it's also to avoid misunderstandings and protect nuance," says Kevin Hendzel, a former White House linguist.

US presidential translators will have passed security clearances, background checks and even sat polygraph tests, before they become privy to sensitive information involved in high-level diplomacy.

"There are no novices that work at the presidential level," says Mr Hendzel. "It takes a great deal of time for an interpreter to reach this stage. They are also experts in the subject matter, and they know getting a form of address wrong can be a deal breaker."

'I am Hillary Clinton, honestly, I am'

Hillary Clinton reported problems getting past White House operators when she was US secretary of state

"It's apples and oranges when you are comparing transitional calls by a president-elect to those of a head of state in the Oval Office," says Mr Yates.

Once Mr Trump is in the hot seat, all his calls will be highly secure and heavily vetted.

"The president will feel like he has just picked up the phone, like any other call, but the call will have been through multiple checks to ensure its fidelity," says Mr Yates.

Sometimes this vetting process can be so tight, the wrong people get cut off. "I am fighting w[ith] the WH [White House] operator who doesn't believe I am who I say," wrote exasperated Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in a 2010 email, external.

Presidents get pranked, too

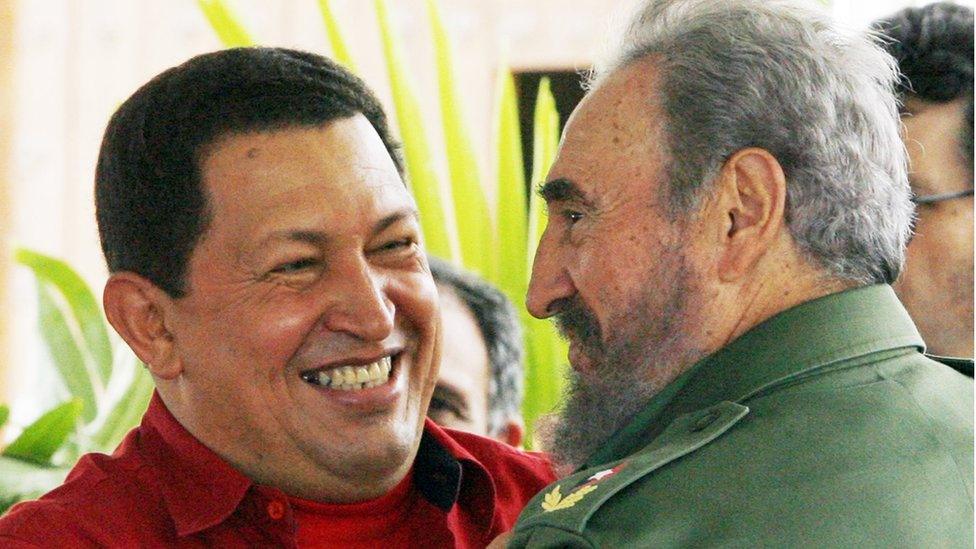

Former Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and ex-Cuban leader Fidel Castro were close allies

Prank calls to presidents are rare, but not unheard of.

Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy fell victim to hoax in January, when a radio presenter phoned imitating the new separatist leader of Catalonia.

In 2003, a US radio station based in Miami scored the double, when it tricked both the then Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and his close ally, the former leader of Cuba, Fidel Castro.

Radio El Zol first called Chavez, pretending to be Castro, and then called Castro masquerading as Chavez, external. When the Cuban realised he had been tricked, he unleashed a torrent of swearwords.

Different radio DJs have also fooled Evo Morales, when he was Bolivia's president-elect in 2005 (pretending to be then Spanish Prime Minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero), and the Queen (pretending to be Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chretien in 1995).

The hotline that is not a phone

The Moscow-Washington hotline, often referred to the "red telephone", is a special, highly secure system that allows direct communication between the leaders of the United States and Russia.

"Contrary to the myths, it's not actually a phone," explains Kevin Hendzel, who worked as senior technical linguist on the project in the 1980s.

The line, used to send text and images (maps, diagrams etc), was developed after the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, when the two countries came close to a nuclear war.

It remains an open channel, allowing instant communication if needed. "Because when it comes to nuclear missiles, everything is measured in minutes," says Mr Hendzel.

- Published1 December 2016

- Published3 December 2016

- Published16 November 2016