Standing Rock: What next for protests?

- Published

Sunday 4 December is being heralded as a historic day for Native Americans, following news the US Army Corp of Engineers will not allow an oil pipeline to pass close to the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota.

Indigenous people, drawn from over 200 tribes, have been protesting against the Dakota Access pipeline for months amidst claims it threatens the Standing Rock Tribe's water supply and has despoiled sacred sites.

An estimated 10,000 people joined the movement, forming campsites close to the most controversial section of the pipeline, near the Missouri River.

The Army Corp's decision, prompted by President Barack Obama's administration, is a major victory for the camps and for proponents of Native American sovereignty.

But will the decision to halt the pipeline last? And what will happen to the vast camps at Standing Rock?

Oceti Sakowin camp, the largest of three protest camps near Standing Rock, celebrated well into the night

"I'm asking them [the camps] to go," said David Archambault II, the Chairman of the Standing Rock Tribe.

"Their presence will only cause the environment to be unsafe," he added.

Heavy snowfall has fallen in North Dakota in recent weeks, increasing the danger of hypothermia in the camps - all which lack permanent electricity and clean water.

Indigenous protesters, who refer to themselves as "water protectors", have been attempting to halt the Dakota Access pipeline for months.

Not all protesters, who refer to themselves as "water protectors", are keen to leave. Many believe the struggle with the pipeline is far from over.

"We are going to accept this victory, but this is just one battle in the broader war," said Tom Goldtooth, an indigenous environmentalist.

"We are going to stay put. We are going to continue to build our peaceful warriors, our troops of peace, and keep our prayers strong. That's what is winning this."

Members of the Sioux regard the land and waters near Standing Rock to be sacred

Energy Transfer Partners, the holding company behind the Dakota Access pipeline, has publically criticised the Army Corp's decision to deny their permit to cross the Missouri River and is expected to file a counter lawsuit.

Chairman Archambault is attempting to arrange a meeting with President-elect Donald Trump, to ensure the next presidential administration upholds the Army Corp's decision.

However, Mr Trump has a turbulent history, external with Native Americans, received campaign donations from the CEO of Energy Transfer Partners, and has previously invested in the oil pipeline.

Many fear he could use his position in government to support the Dakota Access project.

The Oceti Sakowin camp, as viewed from a drone, has come to resemble a permanent settlement

Before any further action is taken, an environmental impact statement will be compiled in the wake of the Army Corp's decision.

This assessment will span the entire length of the 1,200 mile (1,900km) pipeline.

"The process usually takes several months and can last for years depending on the project's complexity," said Andy Pearson, an fossil fuel activist, in a statement on Facebook.

"A generic timeline would be about nine months."

For the duration of this period, at least, the section of the pipeline next to Standing Rock will not be approved.

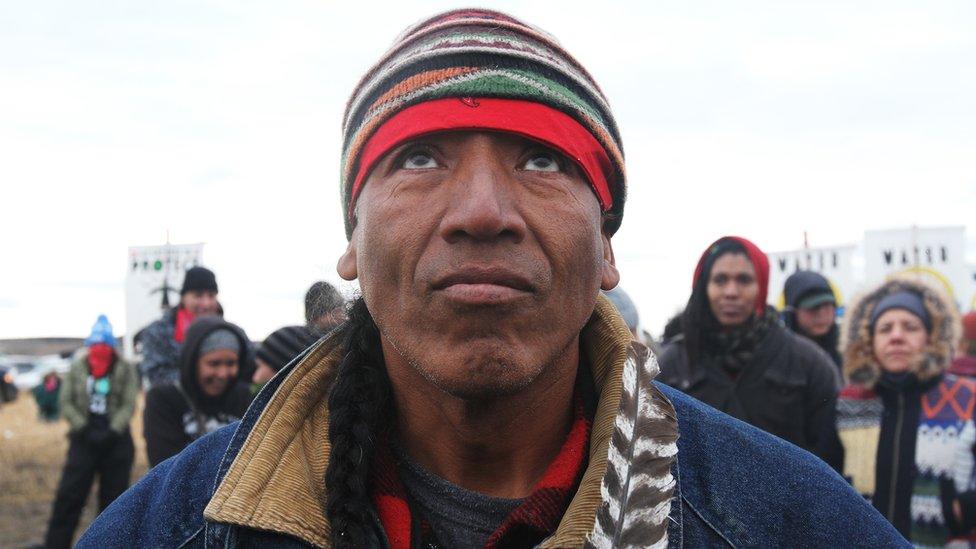

Dan Nanamkin, of the Colville Nez Perce, stands alongside the Cannonball River, where most of the camps are based

Most protesters chose to celebrate on 4 December, rather than dwell on the uncertain future of the pipeline.

"The original peoples of these lands fought with all of our hearts against injustice and won," said Tara Houska, a member of the Ojibwe nation and a former advisor to Bernie Sanders.

"Let this send a message around the world: we are still here. We are empowered. "

The Dakota Access protests resulted in the largest tribal alliance in the US in centuries, amassing support from over 200 indigenous nations

LaDonna Bravebull, the founder of the first protest camp - Sacred Stone - was defiant.

"I am not negotiating," she said, referring to the future of the pipeline.

"I am got backing down. I must stand for our grandchildren and for the water."

Although many protesters have stated a desire to remain in the camps, the bitter conditions of North Dakota in winter may force many to leave

Dallas Goldtooth, one of the leaders of the #NoDAPL [No Dakota Access Pipeline] movement on social media, was measured in his reaction.

"This is not clear-cut, Obama denies the pipeline," he said.

"This is just them [the government] suspending any decision pending further review of other possible routes to cross the river."

The UN condemned police in November, citing their use of tear gas, rubber bullets and power hoses

For the Lakota Sioux people, whose ancestral lands span Standing Rock, the halting of the pipeline had powerful emotional significance.

"It's a good day to be Lakota," said Isac Weston, following the news.

"Everything my family has fought for. Everything our ancestors fought for. It truly showed itself in this four month time.

"This is recovery. There's no more historical trauma. There's no more historical trauma. This is recovery as a people."

The fate of the protest camps near Standing Rock will ultimately be decided by actions taken under President Donald Trump

- Published5 December 2016

- Published2 September 2016

- Published2 December 2016