Hacking: Truth or treason?

- Published

"Information trumps all": Dean Baquet, executive editor of the New York Times

In 1972, the mathematician and meteorologist Edward Lorenz gave a lecture entitled: "Does the flap of a butterfly's wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?"

Lorenz was preoccupied with the idea that tiny changes to a complex system like the weather could produce dramatic and wholly unpredictable consequences.

But it's unlikely that even Lorenz could have imagined what would happen next when Hillary Clinton's campaign chairman John Podesta received an email in March notifying him that his Googlemail password had been compromised and advising him to reset it.

Precisely who was behind the so-called spear-phishing mail - a common form of cyber attack familiar to most email users - and what their motive was, are now at the centre of a ferocious argument in the bitter aftermath of the US election.

The stakes could scarcely be higher: a foreign state stands accused of mounting a campaign of hacking and leaking to help get its preferred candidate into the White House.

"It was the worst experience I have ever had professionally" - Neera Tanden

And whatever the final conclusions of the multiple investigations into the alleged Russian hacking operation, many of Clinton's allies believe the steady trickle of embarrassing emails, drip-fed by Wikileaks through the last crucial weeks of the campaign, may have been enough to deny her the presidency.

Neera Tanden, a former Clinton aide whose engagingly candid emails made her an unwilling star of the Podesta hack, told me the leak had substantially damaged her support among younger voters.

"I believe the leak was a large part of why Hillary had real problems with millennials which is why she did not hit her targets in the three states [Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin]."

I asked her if it could really have made the difference between winning and losing. "Absolutely. And I think people have to live with that."

Dramatic as it is, the hacking of Podesta and other Democrat figures appears to be just the latest manifestation of a disturbing new trend: states combining the techniques of hackers and whistleblowers to mount a new kind of information warfare.

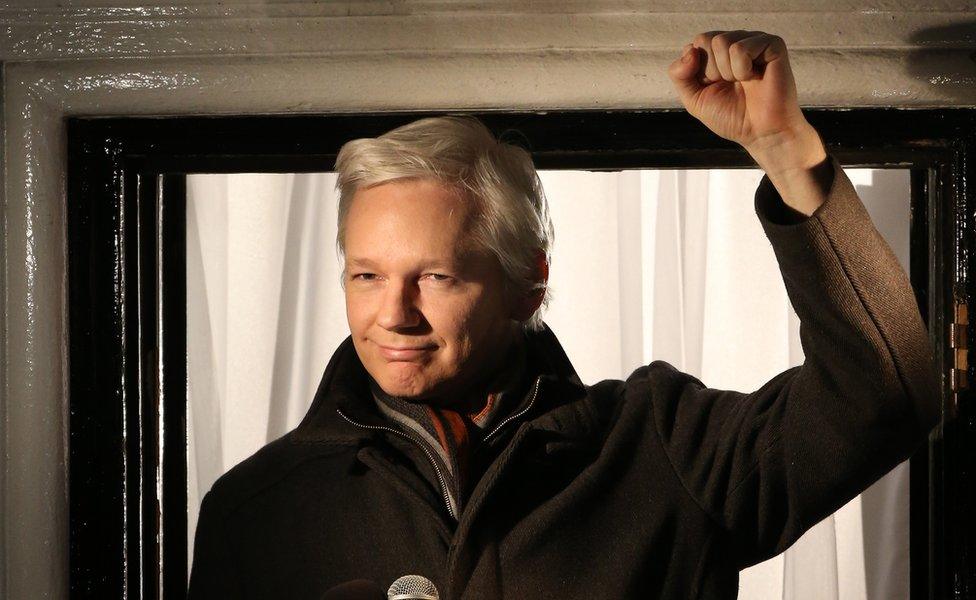

Wikileaks founder Julian Assange: Did the drip feed of leaks aid Trump?

From the hacking of Sony, apparently by the North Koreans, to the dumping of medical records of elite athletes on the internet (Russia the suspect again), the data dump has been weaponised.

It's a development that poses difficult questions for journalists. How should we handle troves of confidential data effectively handed to us by foreign states? Do we risk becoming "useful idiots" when we run precisely the stories that a hostile government wants us to?

It's a question we wrestled with on Newsnight when we ran a series of stories about Bradley Wiggins, based on the medical records of athletes - material widely believed to have been hacked by the Russians in revenge for the banning of hundreds of Russian athletes from the Rio Olympics.

It felt uncomfortable, but the public interest in establishing whether a major sporting figure had broken the spirit of the rules - if not the letter - seemed clear cut.

When it comes to tampering with elections the stakes are rather higher. One prominent victim of another state-sponsored hack told me he thought journalists who feasted on material served up by the Russians with the aim of influencing a US election were committing "something verging on treason".

Dean Baquet, the executive editor of the New York Times, which has run a string of stories based on the hacking of both Podesta's mail and, before that, material from Democratic National Committee figures, told me the thought that he might be doing Vladimir Putin's bidding sometimes kept him up at night.

Many Clinton supporters believe she was fatally undermined by a series of leaks

"Sure it does. But it would keep me up at night worse or at least longer if I had information from a hack that I knew was accurate, that voters and citizens needed to know. That would make me really uncomfortable... Will I lose a little sleep because I'm being manipulated? Yeah. But I lose a lot more sleep if I sit that stuff in a safe."

In Baquet's view, "the information trumps all" no matter how it has been obtained. But I wonder if the ease of leaking digital information has eased our moral qualms about dealing with stolen material.

I asked Baquet what he would have done if the New York Times had been handed a cache of physical documents burgled from John Podesta's house.

He was at least admirably consistent: "I would go through it. And if it was really significant and important I would publish it. And I'm putting a lot of emphasis on significant and important, but I would publish it."

He compared it to the case of Donald Trump's tax return which the paper published during the campaign, with no knowledge of how it had been obtained.

Some have argued that the wholesale dumping of leaked material on the internet, and the media's willingness to report it, is on the way to destroying any expectation of privacy in our digital lives.

Did discovering that producer Scott Rudin considered Angelina Jolie to be "a minimally talented spoiled brat" justify the ransacking of hacked emails from Sony executives?

"Under the veneer of journalism reporters were totally trafficking in gossip," Tanden told me about her experience of being caught up in the Podesta hack.

In the digital world the truth is out there, but does the truth trump all?

Though many questions remain unanswered about the massive leaks of hacked material during the US election, one thing is certain: they are unlikely to be the last.

The German intelligence service has already warned that they fear similar attempts to tamper with elections there next year.

And the man charged with protecting Britain against cyber-attack, Ciaran Martin, director of the new National Cyber Security Centre, told me there was a risk the experience of the US elections would inspire other states to try similar tactics.

One tantalising detail of the great US election hack of 2016 seems to underline the very human frailty that the likes of Martin have to contend with.

When John Podesta received his fateful scam email in March, the New York Times revealed, an aide sent it to his IT department. A staffer replied saying it was "legitimate".

That staffer now says it was a typo - he meant to type "illegitimate".

On such tiny mistakes can the course of history turn. Not so much the flap of a butterfly's wings as a twitch.

Ian Katz is editor of BBC Newsnight. You can watch his full report on iPlayer.

- Published27 October 2016

- Published13 October 2016

- Published12 October 2016