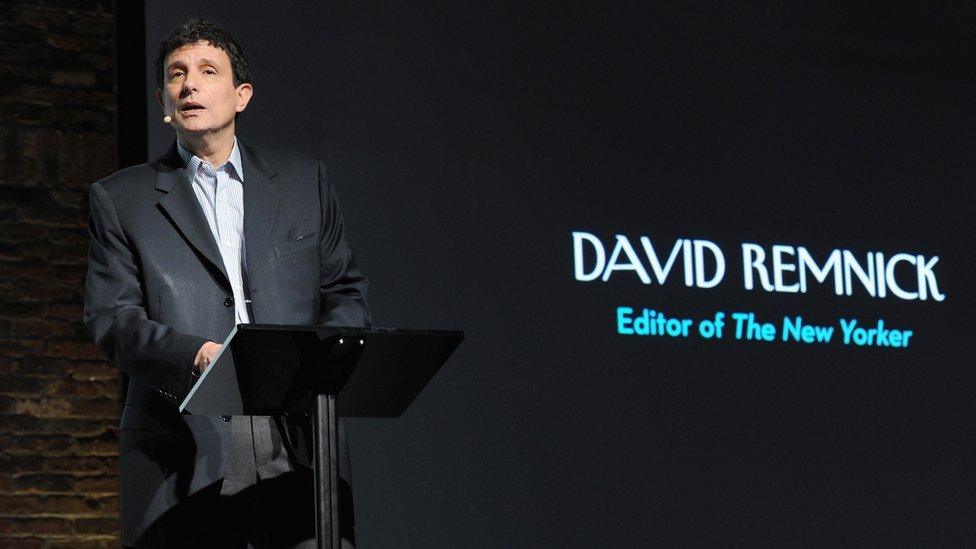

David Remnick: Why Trump’s win is ‘an American tragedy’

- Published

New Yorker editor David Remnick explains why he thinks Donald Trump won the US presidential election

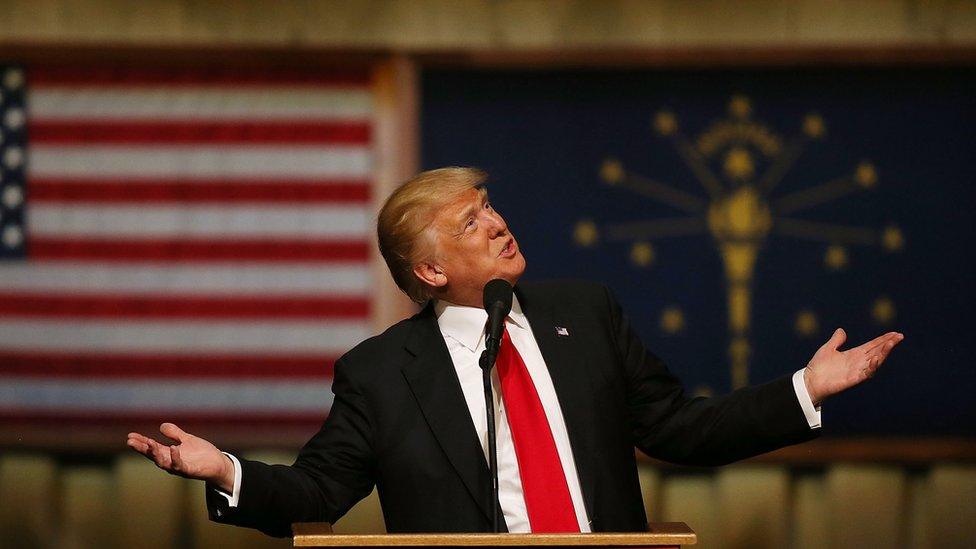

On the night of 8 November, as the seismic result of the US presidential race came into focus, New Yorker editor David Remnick penned an emotional polemic calling Donald Trump's victory "an American tragedy" and "a sickening event in the history of liberal democracy", external.

It made him a hero to many in liberal America and beyond - and a symbol to many of Trump's supporters of an out-of-touch liberal elite.

Newsnight editor Ian Katz talked to him about how the media misjudged the US election, the forces behind Trump's triumph and what happens next.

Ian Katz: How did you get it so wrong? How did the whole media get it so wrong?

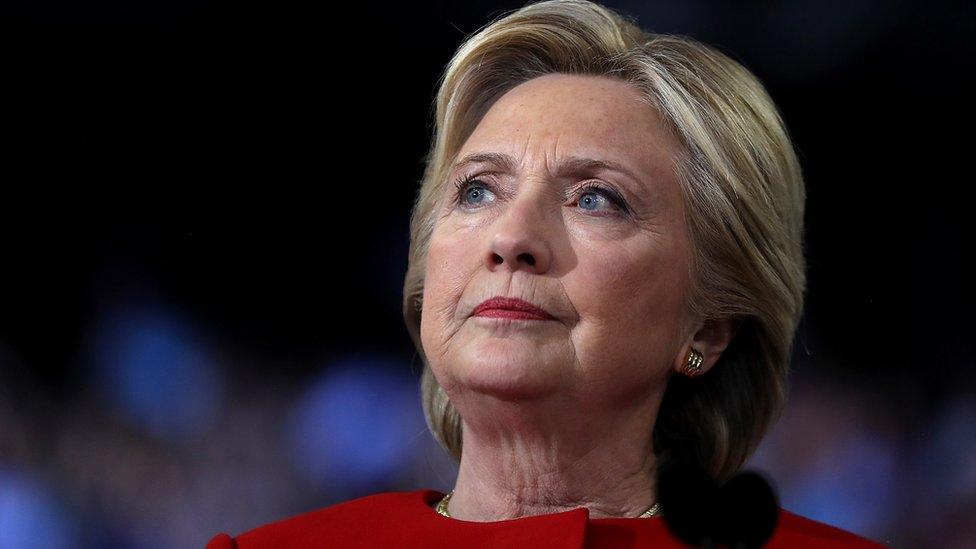

David Remnick: We're not a polling organisation, The New Yorker. And every polling organisation across the board, including the polls inside the Trump campaign, were telling them the same thing. The idea that [Clinton] would lose Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Florida and Ohio? That was an astonishment. I'm not saying that we didn't have other misjudgments along the way, but everyone who was anybody - with some very rare and seemingly outlying exceptions - called the election the same way.

Ian Katz: Aside from the actual numbers, did you all miss that something significant was happening out there in the country? That there was this tide of anger, frustration - whatever it is.

David Remnick: I think the tide of anger and frustration is pretty longstanding. It's the result of globalisation, de-industrialisation in the United States - and not only in the United States - we see it in Europe, we see it in Britain certainly.

It's just that this guy was a way more talented politician in terms of coalescing this anger… Donald Trump broke all the moulds. He was not a conventional conservative Republican. He was willing to say things that were outside that realm.

Ian Katz: What you're saying is it's not that something radically different is happening in the country. It's just you had a politician who came along who was able to harness it?

David Remnick: He's a brilliant, I think pernicious, but brilliant demagogue, who was able to act as a demagogue - a successful demagogue - on the national level the likes of which you've never seen in the United States.

Ian Katz: I mean there are possibly not that many Trump voters who will see Newsnight, but I imagine if they did, they would watch you and think you just still didn't get it.

David Remnick: No, I get it completely. I think this business of "you don't get" - I get it. I've travelled everywhere in this country. I live in this country. I live in a city of immigrants. I have all kinds of relatives, quite frankly, who voted for Trump. I get it. I get it.

Ian Katz: But you live in the world capital of anti-Trump.

David Remnick: Yes, and I'm a Jew and I'm a journalist and I'm all kinds of things that you can make a cartoon of and say horrible things about. Go ahead. I get it. I understand what's happening. That doesn't mean I have to pull the lever and support blindly Donald Trump, and I won't.

Ian Katz: Let's talk about that extraordinary piece that you wrote on the night of the election, external. It went around the world I think within hours. You talked about it being a tragedy for the American public, a tragedy for the Constitution, you talked about it being a sickening event in the history of the United States and liberal democracy. I think a lot of people saw it as a clarion call articulating exactly the fear and anger that they felt in response to it.

David Remnick: And I'm sure some people saw it as somebody who didn't get it, who can't reconcile himself to a new president. You should give him a chance. That's the rhetoric of the day.

Ian Katz: That, or that maybe it was just a little hyperventilating - I think even some people on the left thought actually was this written in the emotion and upset of the immediate hours?

David Remnick: I don't deny it. But I also don't rescind it one iota. I wish I could. I would be delighted if the evidence since election night told me: "You know what? It's going to be OK."

Ian Katz: You did talk about markets tumbling. We haven't seen that, have we?

David Remnick: It tumbled and then the reverse happened. I hope to be completely and utterly wrong. But let's look at what's happened. The most important position in this country in terms of national security is the national security adviser. We now have General Michael Flynn in that position - whose temperament, or his experience, is not first class by any stretch of the imagination.

We have a president who seems to think that the normal business of conflicts of interest do not apply to him. His children are going to run a gigantic business, and yet also participate in the decision making of the White House. He has investments all over the world that depend on the favour of heads of state. He doesn't seem to care about this one iota. If he reverses it, if he sells it off, that will be very encouraging.

Ian Katz: He has said he's selling off his stock, hasn't he?

David Remnick: He sold off his equities - $22 million worth of stock sold in June. He still has no intention of showing the American people what his tax returns look like. His temperament - which is a very important thing in a president - it's completely opposite of the temperament you'd like to see in your grown children. It traffics in hatred, in petulance, in resentment. It's ruled by tweet.

I understand, completely and utterly, this is a divided country - ideologically and in many other ways. I know that people of my political ilk are not going to win every election - to not reconcile yourself to that is to be a child. But this is something different. This is not Mitt Romney winning in 2012 or John McCain in 2008.

It's part of a larger current in the world that I find equally troubling, which is an illiberal current. It has justifiable beefs with the results of globalisation, de-industrialisation. There are all kinds of people in the north of England, in the south, in the Rust Belt of the United States and throughout Europe who are made uneasy by, and have suffered by, all these currents. I get that. I do. I just don't think that the political results that we're seeing in many of these countries are the healthiest thing in the world. I think just the opposite. It worries me deeply and I will not rescind that concern. Why should I?

Ian Katz: But pushing a little against the list of things that you've described that you've seen in the month or so since he won. We've also seen him resile from some of the threats or claims he made during the campaign... "I'm not going to build an actual wall." He has stepped back from some of the things that presumably you would have thought were most worrying.

David Remnick: Sure, but the evidence for concern remains overwhelming. For example, he had a meeting with Al Gore about climate change. If in fact that causes him to appoint people in the key positions regarding energy or in the environment who actually believe in science, terrific. I want the best for my country, to say nothing of the environment and the world. It's much more important that happens than I be right on a political point.

I hope I'm dead wrong. But the currents do not indicate that. Not even close. Gore came to that meeting and he came out of the meetings uttering the cliches of "We had a productive conversation".

He did not leave that meeting saying: "Well thank God he's with science now." If that happens, terrific.

Ian Katz: I guess one of the questions is if you come out of the traps in the way that you did on the night of the election as a journalist with the volume set at sort of 95%...

David Remnick: Ten or 11 - like Spinal Tap!

Ian Katz: 95%, maybe it was 110%. Where does that leave you to go, journalistically, if and when he really does do scary stuff?

David Remnick: Campaigns matter too, rhetoric matters too, promises matter too.

I don't think you would call Donald Trump's behaviour during the presidential campaign one of unification, decency, kindness, dignity. It was one of accusation. Playing the racial dog whistle - it really wasn't even a dog whistle. These are things that matter. It's not just that the campaign happened and now we start from a clean slate. The campaign has led to a pre-presidency that has had a certain shape. I understand that this was not going to be the third term of Barack Obama. I get that too, but what you're seeing is a presidency that is alarming. And when things are alarming, it's incumbent upon people when they're writing to sound the alarm if that's what they believe.

I've seen nothing between November 8 and now - you know a goodly month later - that makes me feel "Ah don't get so hot and bothered, we had Nixon we've had..." take your pick of presidents you don't approve of. It's not that. It's something much more alarming.

A friend of mine here at the office said it's like you've been tossed out of an aeroplane and you feel the sense of alarm, fear. You feel the freezing wind around you but you haven't gone splat yet. And, on the other hand no parachute is opened. No sense of "ah this is a normal event"… There's not that sense - at least not in me. But there is that impulse to make it such and I see it all around me. I see it on television. I see it in the paper.

What I would call normalisation.

Ian Katz: And has that happened?

David Remnick: You see it all over... I understand the impulse. It's a very human impulse always to normalise the situation so that you're not in a state of constant alarm or fear or sadness or agitation.

Ian Katz: But there are a lot of people who will share a lot of your political instincts who would say actually that's a reasonable reaction because in the end this is a country with great constitutional checks and balances, it has a huge state apparatus. They will be all kinds of tempering factors - for all we know Donald Trump will be on the golf course while other people get on with running the country. Isn't that a reasonable assumption to make?

David Remnick: It's possible. It's possible. And all I can think of is that I have my part to play. I have my part to play as a journalist, and to publish fact, to investigate deeply, to speak the truth as we see it, to check facts, to live in a fact-based world - which not all journalism does. It never did, and now it's even more chaotic and bizarre, and a lot of what's entering into the world of political discourse - not least the Trump world - is this notion of non-fact based news. So much so, that the other day there was an attack on a ordinary pizza shop in Washington that had its origins in fake news and a conspiracy theory endorsed by the son of the national security adviser... And Trump himself has trafficked in these conspiracy theories whether it's about the Chinese and global warming or about any number of other things.

Ian Katz: But is there a problem that if you hoist your flag - as you did effectively on the night of the election - that actually when you do this really important accountability reporting you're talking about and you call the government out on lies and you deliver this crucially important fact-based reporting, that actually you are dismissible by the other half of America, because you've shown your colours.

David Remnick: My colours were never concealed. I don't believe in that business - this old 1950s notion of the New York Times, much less the New Yorker - that it was objective, somehow like a science experiment. That scientific method was involved in journalism, I think is a fantasy... What I think is achievable is checking facts. What I think is possible is to have fair argument. What I don't think is possible is to have some fake objectivity - in which on the one side we have 99% of the scientists say... You know on the one hand on the other hand… That's bad journalism. It does the world no good.

Ian Katz: But you've got a problem in this country which is that there is no place, there is no media organisation, platform, which even a plurality of the country can agree to trust.

David Remnick: If you think that French state television or the BBC in England is somehow a common narrative of the country, I think you're fooling yourself. I bet you there are a lot of people, the people in the north of England, who think the BBC is a bunch of lefties.

Ian Katz: Let me ask you a slightly different question about how you do accountability journalism in a post-Trump world, because there used to be a basic set of assumptions about accountability journalism - if you revealed something shocking about a public figure, if you revealed that they have behaved in an extremely contradictory or hypocritical way, it had some impact. And you've now arrived in a world where Donald Trump has survived dozens, maybe hundreds, of the kind of stories that would have killed off a conventional politician.

David Remnick: He has. For a couple of reasons - one because he's extremely skilful. Another because there are so many of them that they seem to come almost at a professional wrestling rate.

Ian Katz: Sort of inflation?

David Remnick: Yeah. But I think to then give up and throw up your hands and walk away and say "Well he's impenetrable, he's Superman" is a terrible abdication and stupid and I don't believe it will last forever.

Ian Katz: So you carry on?

David Remnick: You have to. You must. And at the same time you must also write about, exactly what you're talking about - this other realm of media that's popped up in the age of the internet, in the age of four kids in Macedonia creating fake news channels so they get lots of clicks and it's all anti-Hillary stuff. You must report on it and eventually you'll get through.

I want to remind you of one thing, as dramatic as the Trump victory is - and as much as I'm not denying it, I'm not living in fairyland - Hillary Clinton won the most votes by a substantial margin. We just happened to have this 18th Century antediluvian electoral college system in which my vote sitting here in New York is worth less than my brothers and sisters in Wyoming and that's going to be very hard to overturn. And do you know who was against the electoral college system? Donald Trump.

Ian Katz: You talked a little bit about this being part of an international tide of illiberalism. There are lots of glib things said about the rise of populism. What do you think is going on? What is this tide actually about?

David Remnick: Well let's put it on a human basis in the United States, and I say this with all sympathy. Let's say you were a factory worker in Michigan or in Louisiana and you were making $80,000 a year and you got pretty decent benefits and you could conceivably send your kids to college and there was a certain sense of well-being and upward mobility.

If your factory shut down, you are now, if you're lucky, bagging groceries at Walmart - $25,000 a year and your kids are not going to go to college. And opioids have come to town and they're really cheap. And your life looks a lot more hopeless and you're angry - these currents have been around for a lot longer than Donald Trump. Donald Trump, in a way that I found deeply pernicious, was able to channel them. Now at the same time by the way, let's not forget that employment at the beginning of the Obama administration was in horrendous shape. We were on the brink of a depression, a real depression. Now the employment picture is better than it has been in a dozen years at least.

Ian Katz: The economy is growing.

David Remnick: The economy is growing… So a lot of this is demographic anxiety that we're seeing… There's going to come a point very, very soon in this country where the demographics are going to be that white people, classically defined, will not be in the majority. And let's please not forget that all this anxiety is not unmarked by the fact we are now following eight years of an African-American president.

Ian Katz: These are specific American factors that you are talking about. What is the threat that joins what you saw in this election with elsewhere?

David Remnick: Demographics, globalisation, deindustrialisation, the future of work being very anxious. Look, soon we're going to have grocery stores where you don't need checkout counters.

Ian Katz: We have those!

David Remnick: Yeah, well you're way more advanced. Soon we're going to be in a world of driverless cars. You know what the number one job for men in this country is? Driving stuff, trucks, cabs, buses. What happens to them? Does Donald Trump have an answer for this?

Or is he going to shove driverless cars back? We're going to become pre-modern? In other words, are the answers to all these things to pretend as if we can return to 1957? I doubt that's the case. But the anxieties that grow out of these things are not just anxieties, they're very real circumstances and they have political implications, and one of the most dramatic has been the victory of Donald Trump. It's not the only one.

Ian Katz: And in that piece that you wrote in light of the election, you said we're not heading for fascism because this country won't allow it. But the conditions are there, you said - this may be how this starts.

David Remnick: I think a lot of countries have had the circumstance of believing it could never happen here, and it happened slowly, slowly and then all at once. And part of my alarmism, if you want to call it that, was to, in my own small way, be part of a sounding of an alarm, and a self-awareness that we're not going to repeat history.

I don't think anybody thinks that a funny man is going to come out with a little moustache and an armband, with people marching in an odd way. No, we have a reality television billionaire who's adopted certain ideological and characterological things that are not for the better of this country, in my view. And taken to its logical conclusion, yeah I think it's a form of American authoritarianism at stake. And I think that's an alarm worth sounding.

Ian Katz: David Remnick, thank you.

David Remnick: Thank you.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity