How Pearl Harbor changed Japanese-Americans

- Published

Japanese American internees line up for dinner at a camp in San Bruno, California

The attack on Pearl Harbor shaped the lives of Japanese-Americans long after World War Two ended. As Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visits Hawaii, the internment and treatment of Japanese-Americans during the war continues to resonate in today's political landscape.

When US President Barack Obama and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe stood together in Hiroshima in late May, they made history: President Obama became the first sitting US president to visit the site of the US atomic bomb attack.

On Tuesday they are set to reunite for another historic visit - Pearl Harbor.

When Japanese attacked the US naval base on 7 December 1941, the rest of the world was already at war. Shortly after, the US joined the Allied forces.

More than 50 million soldiers and civilians were killed, making it the deadliest military conflict in history.

Exclusion orders were posted in California, directing removal of persons of Japanese ancestry

But after Pearl Harbor there were consequences for another group: American citizens of Japanese ancestry.

"The Japanese race is an enemy race," wrote Lieutenant General John DeWitt in Final Report, Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942, external. "While many second and third generation Japanese born on American soil, possessed of American citizenship, have become 'Americanized,' the racial strains are undiluted."

In February 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, external, sending 120,000 people from the US west coast into internment camps because of their ethnic background. Two-thirds of them were born in America.

There were ten camps across the US. On average, Japanese American internees spent three years behind barbed-wire fencing.

The Mochida family waits for a bus in Hayward, California that will take them to an "assembly center" in 1942

Their incarceration is relatively well known, but their struggles didn't end there, especially for Japanese-Americans like Lawson Iichiro Sakai, who was 18 in 1941.

"I tried to enlist in the US Navy with three of my Caucasian classmates. They were accepted, but I was not," he said.

"I said 'Why Not? I am an American.' But they said I was an enemy alien, so I was no longer an American citizen.

"It really felt like being rejected by my own country," the 93-year-old veteran recalled.

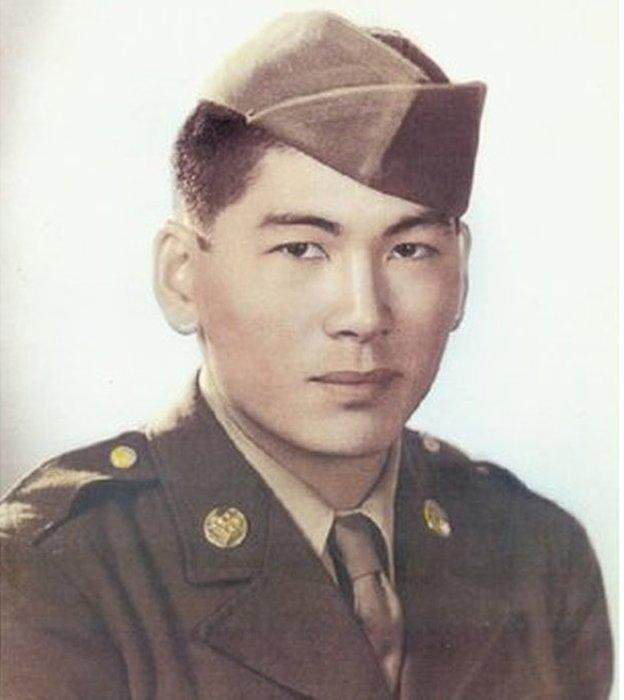

Lawson Iichiro Sakai was initially rejected from the US Army despite being an American because of his ancestry

When the American military needed more soldiers and opened up enlistment to Japanese-Americans in March 1943, Mr Sakai immediately volunteered.

More than 30,000 Japanese-American men went on to serve in the US Army. Many were part of a segregated unit known as the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Under the unit's slogan of "Go for broke!", they were sent to some of the harshest battles.

The 442nd stormed Italy and France, and had an exceptionally high casualty rate. Mr Sakai himself was wounded four times and received a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart.

Mr Sakai said he does not resent the US military for repeatedly sending his unit into harm's way.

"Can you blame the generals for using the best they had?" he said. "No-one wants to die, and no-one wants to see their men die, but we were trying to win the war. By this time, we had proven that we were loyal Americans."

When the 442nd returned to the US in July 1946, President Harry Truman reviewed the unit in a ceremony at the White House, and in a speech told the veterans: "You fought not only the enemy, but you fought prejudice - and you have won."

To continue proving their loyalty to the US, some Japanese Americans worked as translators at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, commonly known as the Tokyo Trials, set up to try the leaders of Japan for war crimes.

David Akira Itami volunteered for the US military after spending a year an internment camp. He was attached to army intelligence, translating Japanese documents, before being posted to Japan as an officer in the US-led post-war occupation.

Translators for the International Military Tribunal for the Far East were torn between their two motherlands

There were very few people who could speak both English and Japanese in 1946, so Mr Itami's job was to make sure the work of the interpreters was accurate. In the trial record, he attempted to let the Japanese generals finish their sentences before being interrupted.

But Mr Itami's experiences may have taken a toll. He took his own life at the age of 39 in 1950, shortly after the end of the tribunal.

The treatment of Japanese-Americans during the World War Two was denounced by President Ronald Reagan in 1988 as "a policy motivated by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership".

He signed the Civil Liberties Act, external to compensate more than 100,000 people of Japanese descent who were incarcerated in internment camps.

But last month, Carl Higbie, a supporter of President-elect Donald Trump, said the wartime internment of Japanese Americans is a "precedent" for a registry, external for all immigrants from countries where terrorist groups are active, a move that would largely affect Muslim American immigrants.

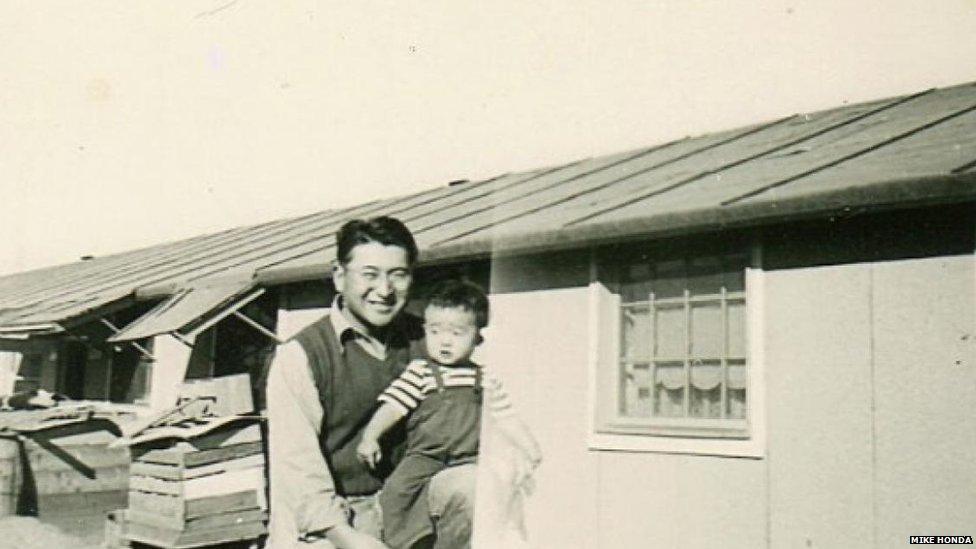

Young Congressman Mike Honda and his father when he and his family were forcibly imprisoned at the Amache internment camp in Colorado

Japanese-American lawmaker Mike Honda, who was sent to an internment camp as an infant, said the remarks are "beyond disturbing".

"This is hate, not policy," said the 75-year-old congressman in a statement, external. "This policy of registering a minority reduces us, placing our future in the hands of small-minded bigotry of the 1940s.

"No one should go through what my family and 120,000 innocent people suffered regardless of their race or religion or any other way they would choose to try and divide us."

In an interview with the BBC, the congressman said he hoped Mr Trump "will prove people wrong by making a clear statement", and was withholding his judgment until then.

"But his cabinet picks so far make me nervous," Mr Honda said. "He may be swayed by those with more extreme views who he has selected to be a part of his administration."