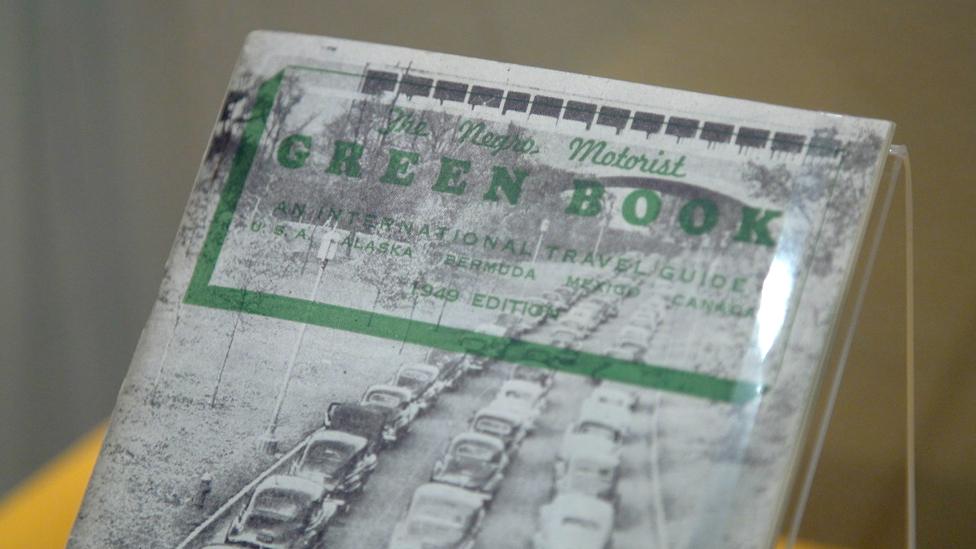

A postman wrote a Route 66 travel guide for black people

- Published

America's Route 66 is the ultimate symbol of freedom and mobility, but before the 1960s the motorway could be fraught with danger for black travellers. A unique travel guide helped keep them safe.

Travelling already has its stresses, but for black families and businesspeople in the 20th Century, trying to navigate through the many "sundown towns", where African Americans were forbidden after dark, added an extra threat.

But they had some help. From 1936-66, an entrepreneurial postman from Harlem published and sold The Negro Motorist Green Book, an annual guide to safe places along Route 66 and across the country.

"It was so much more than a black travel guide," says Candacy Taylor, who has been documenting Green Book sites along Route 66.

"It was more than hotels and restaurants. It listed different stores and churches, barber shops and beauty salons and mechanics."

Victor Green, the postman who created the guidebook, knew that a flat tyre in a "sundown town" for a travelling black family could become much more than an inconvenience.

Candacy Taylor has been documenting Green Book sites along Route 66

Violent racist attacks were real possibilities, external for black travellers, external. Humiliation and intimidation were almost guaranteed.

Ms Taylor stumbled upon the Green Book while writing about Route 66.

She was surprised the guidebook wasn't well known or that the businesses that helped black travellers weren't being valued as culturally significant sites.

For African Americans who travelled during segregation, many of the sites will never be forgotten.

Actor Lamont Easter remembers family road trips fondly and marvels that his dad shielded him and his siblings from discrimination.

The children never realised until they were much older that some places were off-limits to them.

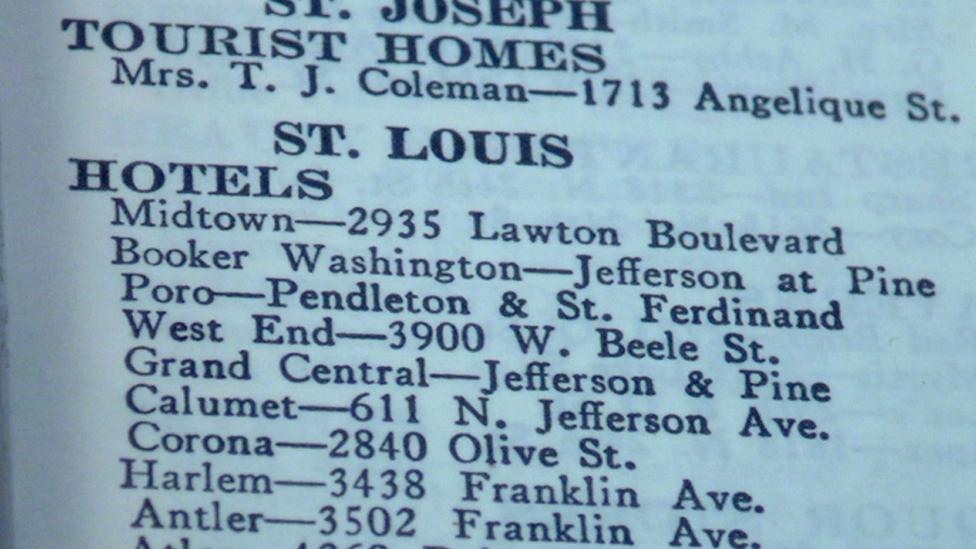

A list of safe hotels in one version of the Green book

His father, James Easter, was in the Navy and the family often stayed at military bases when they travelled or they would go camping.

But Mr Easter had a Green Guide "as a security blanket".

"I was always concerned but not worried," he said of driving across the country.

"I was a mechanic and an engineer. If I broke down I could fix things."

Mr Easter knew what it was like to sit on the back of the bus and be forced to wait outside a restaurant while his white colleagues ate inside - and he didn't want his children to experience the same.

"I had a wife and kids going with me across the country and I didn't want to subject them to any unpleasant things," says Mr Easter, who is now 81.

He said black families typically packed picnic lunches so they wouldn't be caught hungry near a row of restaurants unwilling to serve them.

The guidebooks were sold in Ebony Magazine and at Esso Standard Oil stations along highways.

In rural areas, the book listed private homes where people could spend the night safely in towns where hotels wouldn't accommodate black customers.

How this Green book helped black travellers

The books were modelled on similar guidebooks for Jewish travellers.

"It's an incredible archive of black entrepreneurs - look at the people who were opening their businesses up," Ms Taylor says.

"There was a great variety of black business and exclusive prestigious properties, like the Biltmore Hotel" in Los Angeles and The Dunbar Hotel, which was the heart of Los Angeles' African-American culture in the 1930s and 1940s.

Despite their fame, stars like musician Louis Armstrong, boxer Joe Louis and jazz singer Billie Holiday couldn't stay anywhere they wanted during segregation and The Dunbar, built by a black dentist, was "the Waldorf Astoria for black people", Ms Taylor says.

Forty-four of the 89 counties along Route 66 had sundown towns, she says, adding that the West Coast was in many ways more dangerous than the segregated South, because in the South people knew where they stood.

Racist businesses were clearly marked: No Blacks.

Stefan Bradley, a professor of history and African-American Studies at Saint Louis University, says the book helped people avoid the humiliation of being refused access to a restroom or simply buying coffee and a pie in a restaurant, while also keeping them safe.

Clifton's Cafeteria, in Los Angeles, was listed in the guide

"It was small but it was powerful because it spoke to the idea that black people would find a way to get around the kind of racism and oppression that existed in the country at the time," Mr Bradley says.

"The idea that one man - not a superhero but rather a postman - would figure out a way to help African Americans feel human when they were travelling - that makes it a powerful little book."

Ms Taylor says she is working with city officials in Los Angeles to help protect and preserve some of the historic sites.

"We should at least put a plaque up so somebody knows - at least before they are all torn down," Ms Taylor says.

She has catalogued more than 2,700 locations over the last few years and is pushing for more preservation, adding that there is a lot of misinformation on the internet about Green Book sites.

"There is so much we don't know," Ms Taylor says. "People had no idea how many sites there were - it's very exciting for historians."